I’ve been trying to climb the side of this sheer cliff face for several hours using only my feet. The path is tricky and winding but at this point I know the footholds better than the faces of some of my friends. Some of them involve slightly shimmying my feet on a thin ridge of rock. Others involve lifting my leg out from the cliff face, swinging it over, and planting my foot until I feel something firm enough to lift my body up. I misjudge a step, my character tumbles; his body ping pongs back and forth between the side of the path and the conveniently built spiral stairwell next to the path, his head catching the green steel railing. I feel numb at this point. My character groans, gets up, I try again. This is the Manbreaker in Baby Steps, an unpleasant task that I have been told I do not need to do.

This article contains some plot spoilers for Baby Steps.

Baby Steps is the latest game from Gabe Cuzzillo, Maxi Boch, and, of course, Bennett Foddy. You may know Foddy from QWOP, GIRP and Getting Over It, games infamous for abstracting movement so that the player will often cartoonishly fall down. It follows an emotionally stunted thirty five year old man named Nate (played by Cuzzillo) who is stuck in a cocoon of permanent social isolation. Nate smokes a lot of weed, lives in his parents' basement, watches One Piece, and eats a lot of pizza. Suddenly he is Isekai’d from his couch to a surreal, looping, mountainous world that gradually slopes upwards to a mountain top. A helpful man named Jim (played by Foddy) attempts to explain the situation to him and give him shoes, but Nate refuses any help, instead insisting he’s just gonna go. The only thing he wants is to find a toilet because he needs to pee quite badly and refuses to pee outdoors.

Like QWOP, Baby Steps approximates natural movement in a way that feels stilted and unnatural at first. Whereas QWOP binds your thighs to the Q and W and your calves to O and P on the keyboard, Baby Steps binds the act of raising your left and right legs to L2 and R2 respectively, with trigger depth determining how much you raise your leg. A raised leg is then moved using the left analogue stick. This, along with Returnal, is one of the few games that uses the Adaptive Triggers on the DualSense beautifully as it adds real texture to the sensation of walking. When you actually get good at using your legs, the sensation of walking feels organic in a jarring way.

Baby Steps hit me at a strange time in my life. I currently have a broken foot with several pins sticking out of it. I have been sleeping on my couch since early August so that I can properly elevate my leg and not disturb my girlfriend’s sleep. I am a month into using a prosthetic crutch that is not unlike a peg leg, a device that forces you to learn how to walk again in a stilted and alien way, but one that becomes second nature over time. I even went to a four day techno festival in nature that I have been going to for over a decade because my pride refused to let the broken foot win. The experience was brutal on my body, yet rewarding. I frequently climbed a steep incline to my cabin and crossed a treacherous floating bridge over a lake using trekking poles to stabilize myself. People kept offering help that I often refused. I was alarmed by how quickly I parsed Baby Steps’ internal logic.

Throughout the game, Jim constantly offers Nate help. He is like a bodhisattva, a sherpa whose only purpose in this world is to help the others get to the top of the mountain. And yet, through a combination of anxiety and stubbornness, Nate steadfastly refuses to outwardly accept help. His repeated rebukes of Jim builds throughout the entire game, and Nate’s bullshit attitude and awkwardness increasingly wear away at Jim’s patience. As you climb the mountain, going from biome to biome, you eventually see Jim’s masterpiece in the distance: a 250 story green spiral staircase (seemingly based on a real one in the Taihang mountains) that he built for all the hikers to get to the top of the mountain easily.

Jim is pleased with his staircase. It helps a lot of people achieve their goal of climbing up the mountain where they had previously toiled. But Nate is Nate, and he does not want to take it, instead pointing to a winding and dangerous mountain path.

JIM: “You can’t, it’s too hard for you.”

NATE: “It’s not that hard.”

JIM: “They call it the Manbreaker.”

NATE: “The Manbreaker?”

JIM: “Yeah, because many men have been broken trying to get up that thing.”

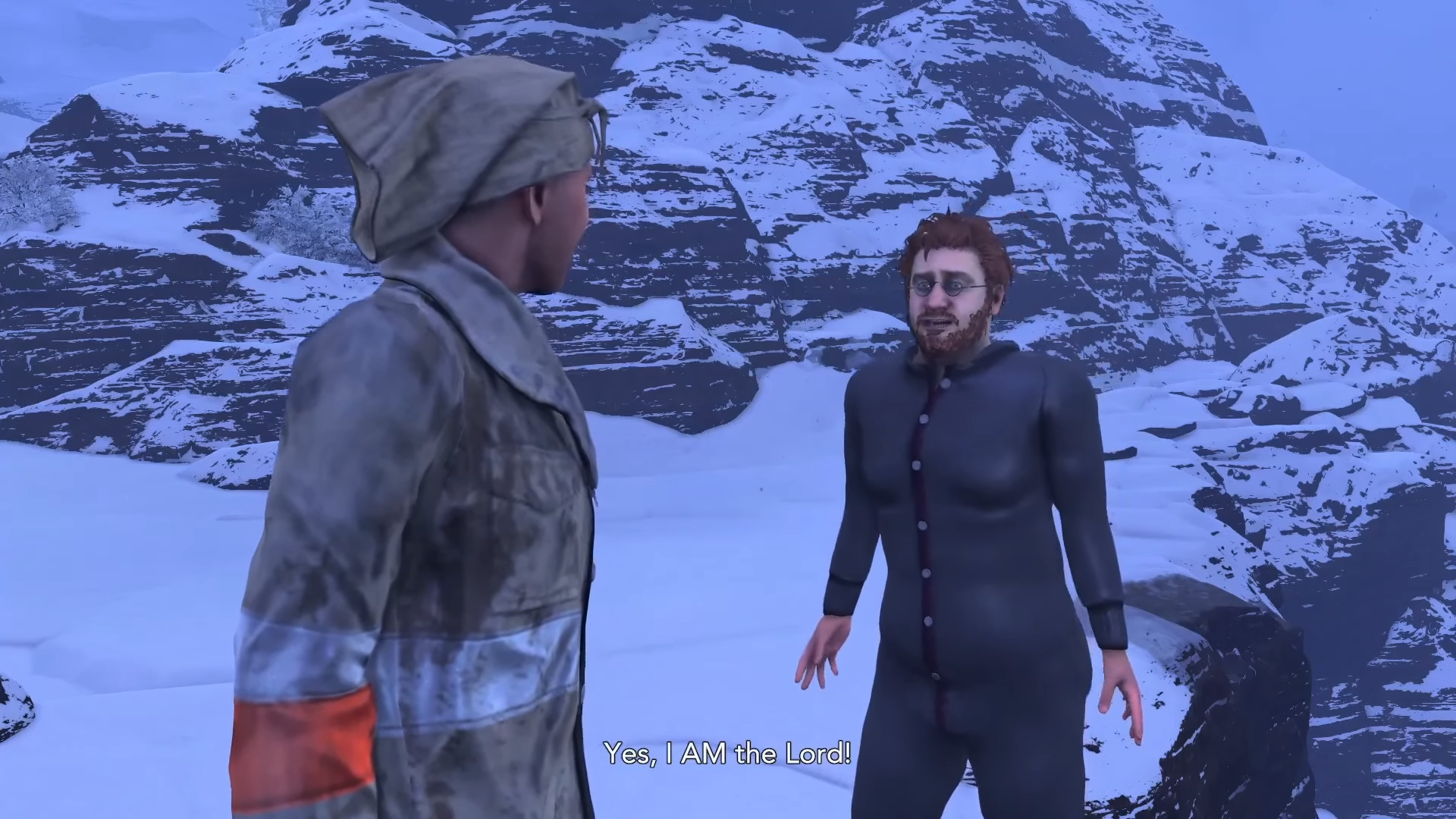

Nate boasts that he’s going to do it while Jim tells him if he does that he’s going to be bashing his head against the Manbreaker for the next five years. This devolves into childish bickering, with Jim forbidding Nate from climbing the stairs, insisting that if and when he gives up on the Manbreaker, he must call Jim “lord,” because he is the lord of the stairs.

Narratively this is a beautiful setup. Baby Steps is ultimately a game about swallowing your pride and accepting help, but one that fills itself with many totally optional challenges. It can be a brutally difficult game, but it is often only as hard as you want it to be. Nate has fucked you here a little bit, because he is objectively in the wrong and should just take the stairs. But Jim is being a dick, something he has every right to be given Nate’s behavior. It’s not that I wanted Nate to win, I just had to know what happened if Nate actually pulled that off. So my long journey on the Manbreaker began.

The Journey Begins

What makes the Manbreaker so punishing is not that the individual steps are harder than what you’ve faced, it’s that there’s a lot of them. The cliffs are constructed in a way that if you fall you are unlikely to go further than the base of the stairs, but you will often have to start from the beginning. Individual steps are just difficult enough to seem doable with a handful of distinct choke points in between. If you know what you are doing and don’t miss a single step, you can scale the entire thing in about twelve to twenty minutes. The real problem lies in landing every step, not slipping once.

There’s an annoying slope that requires you to quickly scurry early on that will regularly cause you to slide off until you figure out the momentum of a scurry step. Sometimes the game gives you multiple ways to approach the same obstacle: one challenge right before the halfway point can be solved either by shimmying in a narrow ledge to your right or, more consistently I discovered, by placing your foot on a tiny outcropping to the left of the rock and swinging your legs over a few ledges back and forth twice.

At the halfway point through the climb, either on the stairs or the Manbreaker, you will receive one of two cutscenes. Both involve Mike, a friendly hiker also played by Foddy who you have interacted with in the past. If you are on the stairs, Mike will be on the Manbreaker. He says Jim told him not to take the stairs, saying “Mike, you’re ready.” He feels confident in how far he has come in his abilities and expounds on the rapturous, sublime nature of climbing the path. Nate says the stairs are pretty good too. If you are on the Manbreaker, Mike instead is on the stairs. He asks you why you are doing that, and instead suggests you give up and take the stairs. No matter what path you take, the game tests your conviction by suggesting you are taking the wrong one.

My girlfriend watched with a combination of bewilderment and schadenfreude as I subjected myself to this over several evenings. “Oh yeah you see you should not have done that,” she would chime in when my foot slipped and I tumbled hundreds of painful feet. At first I would get exceedingly pissed off whenever I fell off. And yet every time I fell off, I got less pissed. As the number of falls increased and I memorized my footholds, I realized that the Manbreaker was teaching me Baby Steps at a higher level. The frustration subsided. The Manbreaker could not hurt me. I locked in.

On locking in

When I lock in, I think of a particular edit from streamer Northernlion. He is playing The Game of Sisyphus, a game clearly indebted to Foddy’s Getting Over It. The video is a supercut of him shouting a mixture of zenlike phrases and Instagram grindset guy advice. He is attempting to push the rock up the hill while the song "paranoia" by Kentenshi (itself a remix of the song "Young Girl A") plays. Northernlion’s advice is sublime and contradictory, punctuated by an aggressive drum machine and distorted Vocaloid samples. It is a speech that seems to suggest that everything is possible and nothing is possible, that your actions are both meaningless and, simultaneously, the only point in the world. If you listen to it enough times, you begin to reconcile those contradictions. On an even longer timeline, it begins to resemble a prayer.

“Lock in. Lock in. Get it twisted,” Northernlion begins. “If you lock in you can do anything. Motherfucker. Get it twisted, your actions impact nothing, your fate is predetermined, the only thing that you can change is your reaction to it. You can do anything you set your mind to, the world is a playground designed for you and only you to achieve your highest level ambitions. If you wait 90 minutes to wake up until you drink your first cup of coffee, nothing can stop you. If you duct tape your mouth when you fall asleep, nothing can stop you. Get it twisted. You are a pawn in a universe chess match. You mean nothing to God if they even exist. You’re a rounding error. You’re two pennies on a Fortune 500 company’s balance sheet; they don’t care about you in the slightest. Get it twisted. Everybody gets what they deserve in this life. If you put in effort you can achieve anything. Successful people are better people. Get it twisted! The circumstances of your birth determine where you are going to go. Nothing else matters at all: your own level of education, your attitude, your level of effort, your friends, your network, your business, your credentials. Motherfucker!”

Those words swirled around in my head with every attempt, their contradictions becoming a centering hum. Waves of frustration would hit me, subside, and the words would redouble my resolve. Nothing was preventing me from leaving, but I could not leave. I had spent too much time studying the cliff face, learning its contours, the end was in sight. I would finish this. Lock in. Get it twisted.

Other broken men

I was not the only broken man attempting the Manbreaker. As I was throwing myself off the mountain I saw others attempt this. Frequent contributor Ian Walker was being punished by the path, as was Giant Bomb’s Jeff Grubb, who streamed his attempts and got to the top before I did.

“I was already really into Baby Steps by the time I got to the manbreaker, and I was already onboard with the game's central metaphor (as I see it),” Grubb told me. “That is that all you can control in life is the next step that you take. Even if you're not that great at taking steps, that's the only option you have. Even if you get lost, that's the only option you have. So just take the next step, and eventually you'll take enough steps and you can look back and say: look how far I've come.When I got to the Manbreaker, it felt like the culmination of that idea but also an argument against it.”

“I think a lot of people will take the cutscene between Jim and Nate at the Manbreaker as a challenge to take the Manbreaker. But I definitely took it as a challenge to take the stairs—to ask for help,” he said. "Someone built this tool to help me get to where I'm going, but the toxic individualism—that has fueled me in life and that has been ingrained in me by my culture—wouldn't let me.”

“I need to feel like I did it on my own,” Grubb continued. “And I think that's actually a weakness. A flaw inserted into me strategically by a ruling class that does not want me to rely on others because then we might actually start working together.”

Mercy in design

For as intricate and brutal as the design of the Manbreaker is, it is also compassionate. Each time you hit a new part of the Manbreaker you have to learn the encounter, and by the time you get to the upper layers of it, the prior parts begin to be tedious. But halfway through the run, at the point where you talk to Mike, the stairwell and path become close enough to almost touch for two levels. It is possible to give up on the Manbreaker at this point and take the stairs, or to use the stairs as a shortcut for finishing the end of the Manbreaker. If you decide to take the shortcut after you’ve already gotten the cutscene, the game does not penalize you for this and gives you the same outcome as if you had done it in one go. This is how both Jeff Grubb and I attempted the final climb. I refuse to call anybody "lord," but I’m old enough to know that repeating the bottom wasn’t proving anything.

The last series of steps in the Manbreaker are by far the worst in the whole run. The first step requires you to place your foot gently on a declining slope, let your body slide for half a second, then catch the platform with your other foot. You could spend an hour just mastering the timing of this one step. But the game dispenses this complex task with a small kindness, and positions most of these steps save the last few over your previous path. If you fall, you will more than likely have a second chance.

This is the end

(SPOILERS FOR THE END OF THE MANBREAKER/STAIRS BELOW)

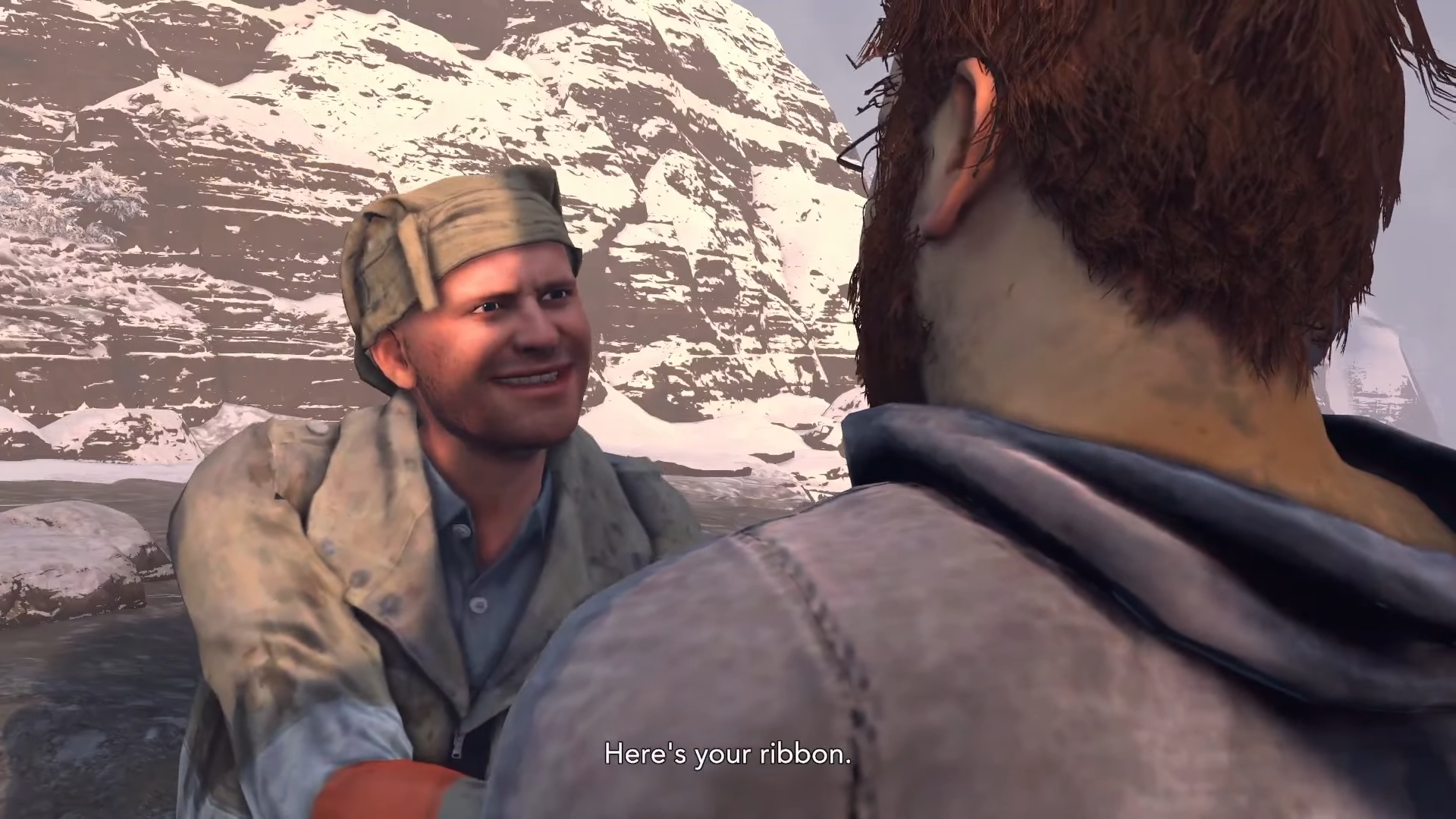

This scenario has two potential endings. If you swallow your pride and take the stairs the whole way up, you are ambushed by Jim at the top. He is glowing and smug and makes you call him lord. He gives you a little ribbon and proclaims you are in an elite club called “Jiminny’s Crickets,” and the game gives you an achievement for this, almost condescendingly.

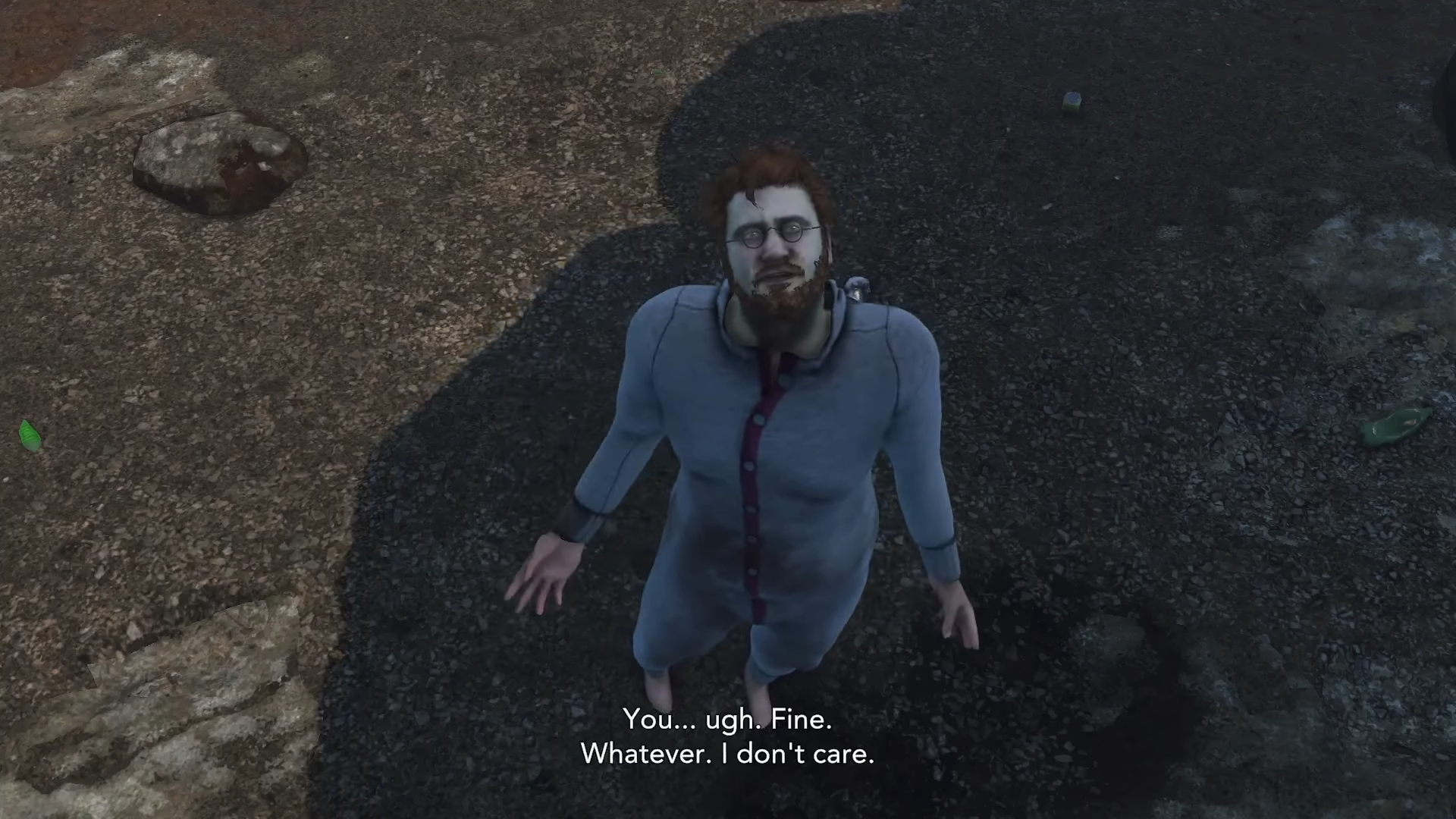

If, on the other hand, you decide to take the Manbraker then Nate arrives at the top gasping and gloating. Jim is confused, unable to comprehend how Nate did it. Nate boasts that the climb was easy and suggests that perhaps the stairs were superfluous.

“But if the stairs are superfluous then maybe…Jim was superfluous,” Jim says in a broken voice, adding, “Lord.”

Jim then proceeds to throw himself off the cliff face (he is probably fine considering everyone in this world is immortal.). Nate broke a helpful man’s spirit, shattered Jim’s purpose in life, learned nothing about accepting help, and the game gives you no achievement for it.

As toxic as it is, the Manbreaker felt worth it. After learning to carefully bottle up and regulate my emotions, triggering the cutscene caused a rush of relief to flood through my body all at once. The Manbreaker did not break me, but it changed me significantly. It is not simply a crucible of difficulty, but a beautifully written and designed riddle about rancid pride and sublime challenge chiseled directly into the cliff face. To beat it transforms you into a Baby Steps climbing god just as the game reaches its logical conclusion.

“What do you do now?” my girlfriend asked.

“I guess I’ll just finish the game,” I responded, and climbed to the game’s conclusion at a breezy, unworried pace.

Correction, 10/8/25, 12:55pm--An original version of this article occasionally misstated the name of character Jim.