The first time I get a good view of Cyberpunk 2077’s Night City is from the window of a private taxi. The driverless flying car departs from a portal high up in the side of my corporate employer’s headquarters and soars over a packed, four lane traffic circle. I sip champagne as neon towers slide past, megabuildings whose gargantuan size would make Denis Villeneuve blush.

The car is taking me to a bar to meet a friend. As the vehicle swoops down, the automation warns me that there is no suitable landing place for an aerial vehicle. In other words, there’s nowhere to park.

I override the warning. The cab parks illegally on a basketball court, upsetting the people currently shooting hoops. I punch them in the face, because this seems like the kind of thing a corpo like me would do.

Parking isn’t a big deal in Night City, because Cyberpunk 2077 is a game and nobody enjoys parking. You can leave your car, motorcycle or neo-militarist armoured SUV wherever you like and recall it later with the press of a button. Cars are almost always in motion, and it’s rare to see street parking or a parking lot. There aren’t even bike lanes; Night City is a place where the car is king.

Clearly the designers at CD Projekt Red understand what many real world urban planners are starting to grasp: parking sucks the life out of a city. This representation of a car-centric dystopia can’t actually be too car-centric. It’s fun to drive around, sure, but Cyberpunk 2077 isn’t a game about driving.

“We were creating a game, an experience that has to be super fun for the player to enjoy,” Kacper Niepokólczycki, environment art director at CD Projekt RED, told me. “You can explore the world in a vehicle, on foot, or swimming. We tried our best to make sure any of those methods gives you a fun and different experience.”

If only North American cities thought the same way.

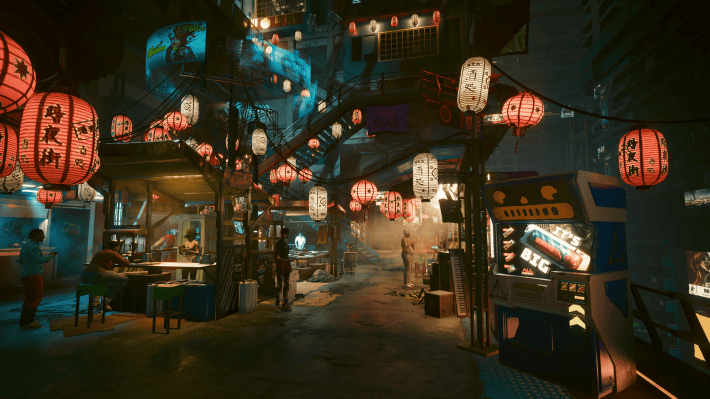

In-game, the meeting in the bar goes poorly, and afterwards I get dropped off by the Kabuki Roundabout. I head into a lively pedestrian market in the centre of the traffic circle. There are street food vendors and a place to buy guns and cyberware. It’s all open 24 hours a day, so you can pick up ramen and a revolver whenever you’re hungry for food or violence.

Night City is full of places like this: walkable public space with restaurants and retail.

“In some places we were able to close traffic and create denser crowds — so you can really feel like you’re in the tight streets of an Asian-inspired city,” said Niepokólczycki. “Just like the breathtaking vistas and interesting, layered environments, we wanted to make our crowds stand out just as much.”

One evening my companion Johnny Silverhand (played by Keanu Reeves) stops me as I pass a busker and compliments his playing. We agree to go check out an old club where Silverhand used to play gigs himself, and are led to a stall in a local market where a crusty old rocker is selling bootleg tapes of Silverhand’s band Samurai. This is often how subplots emerge in Cyberpunk 2077 – chance encounters and following leads.

The game needs places where the player can walk freely and have seemingly-random encounters like this. For Niepokólczycki, it doesn’t matter if a player only experiences one or two of these chunks of side content; it's about the discovery. “[Night City is] a living, breathing city with its own ecosystem, and you are just exploring part of it,” he said.

The same is true in real cities, though on a different scale. A store, venue or art installation doesn’t have to be for every single person in the city, but it can delight some people as they happen across it. One of the most joyous things you can do in a city is to explore and discover.

“Seeing the amount of YouTube videos of players exploring Night City for hours and hours straight on foot — which by the way, is amazing to see — it looks like we succeeded. I love to watch those videos!” said Niepokólczycki.

AppleTV’s upcoming adaptation of Neuromancer, William Gibson’s 1984 novel which defined the cyberpunk genre, is currently being filmed in Tokyo. Night City may be physically located on the west coast of North America, but it’s easy to see the influence of East Asian cities like Hong Kong and Tokyo in the bright neon lights and loud advertising. That influence is also there under the city’s skin. It’s in the way that land is used and regulated, known as “zoning” to urban planners.

CDPR had two urban planners on the development team for Cyberpunk 2077. Niepokólczycki said there was push and pull between the game’s artists – who were excited to draft a flamboyant, futuristic sci-fi city – and CDPR’s urban planners, who “tried to do what they do best — build a believable, functional city that could actually exist. They acted as the voice of common sense.”

If this were a truly North American city, then vast swathes of Night City would be zoned for residential use only. In my own city, Toronto, this is known as the “yellow belt,” because residential is marked in yellow on the city’s official land use map. You cannot open so much as a coffee shop or convenience store in the yellow belt. It’s all homes, most of which are detached single family houses. This type of zoning is known as “exclusionary zoning,” because it excludes most uses.

In real world cities like Toronto there have been attempts by urban planners and progressive politicians to do away with exclusionary zoning, but they’re often met with pushback from local homeowners who want to “preserve” or “protect” their neighbourhoods. This is ultimately futile: populations grow, leading to a shortage of housing, while children age out of their parents’ houses and move to the denser apartment-centric neighbourhoods they can afford. Eventually you have what we see in Toronto today: once-lively neighbourhoods where populations are falling and schools are under-attended. Meanwhile, the areas where development is allowed are experiencing massive growth, becoming densely populated with over-used amenities and services.

When you walk through these residential-only parts of Toronto, it’s hard to deny that they’re often attractive to look at but fundamentally boring to linger in. They’re places to come back to after spending the day at work or play elsewhere. They would be untenable in a video game; there wouldn’t be much point creating a yellow belt in Night City.

Instead, Cyberpunk 2077 has land uses much closer to that of Tokyo, called “inclusionary zoning.” In Japan, even the most restrictive zoning still allows for small shops on residential streets in the same building as a private residence. This has made Tokyo an eminently walkable city where residents can go about their days without hopping into a car. In fact, Tokyo has the lowest car use in the world. About 12% of trips are completed with a car, whereas 17% of trips are done with a bicycle, according to Daniel Knowles’ book Carmageddon.

In Night City, there are vendors crammed into corners and in-between spaces. Apartment buildings have retail, boxing gyms (or in Megabuilding 8 it’s more of a baseball bat gym), and social spaces right outside your door. When you wander the city you are encouraged to interact with it. That’s true in Night City, as it's true in Tokyo.

In most games cities feel like they have sprung to life fully formed like a beautiful painting, but that’s not how real life cities are built. The collaboration between CDPR’s artists and urban planners created a city that feels like it has a genuine history. The liveliness of the streets and the chance interactions are a huge part of it, but the aesthetic is key, too.

Let's step outside science fiction for a second and take a look at some fantasy cities in The Lord of the Rings: Rivendell, Osgiliath, Minas Tirith. They’re otherworldly expressions of stone and water, flowing beautifully from one arch to the next. They’re stunning to look at, and utterly unrealistic: No real city’s architecture remains that uniform. Even places like Paris or Vienna, with their great reconstructions of the 19th century, can’t maintain this level of coherence. Humans just don’t work that way; we’re messy creatures, subject to economic pressures and aesthetic disagreements.

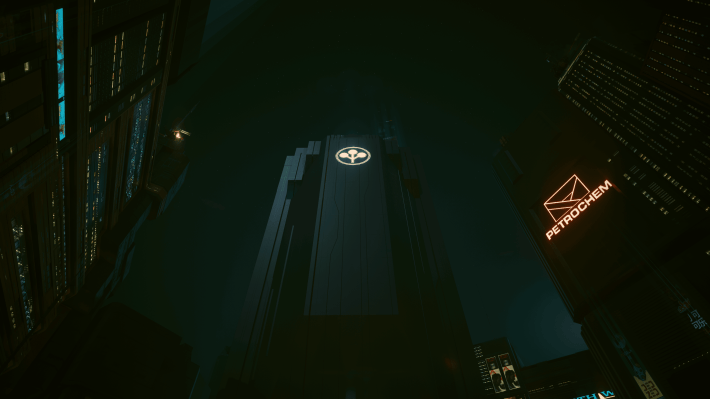

Night City, on the other hand, is an architectural melting pot. Neon signs are everywhere, but the buildings are a chaotic assortment of styles, jumbled and squashed together. This doesn’t mean that the city feels incoherent as a whole. Neighbourhoods are still distinctive, with subtle stylistic variations that give the player a sense of place.

To achieve this, Cyberpunk 2077’s designers created four architectural styles: Kitsch, Entropic, Neo-military and Neo-kitsch.

Niepokólczycki said that “Kitsch was trying to pretend it looks expensive, when in reality it was a cheap style that used materials and technology that would break or become damaged easily. It was a disposable style in that regard; when something breaks, you just make another one of the same quality.” To me that sounds a lot like the McMansion-style architecture you see in so much of middle America.

Entropism, on the other hand, is a style based on poverty and a severe lack of resources. In a nutshell, this style visually tells the story of the very poor social layer of our world. Its central motto is “Necessity Over Style.”

These architectural styles are not defined with great specificity; Niepokólczycki did not say that Heywood should have Mansard roofs and homes in Santo Domingo are built with yellow brick. Instead, the buildings reflect the people who occupy an area. In this hypercapitalist, gun-centric future, Neo-militarism is associated with corporate headquarters; think sleek lines, dark colours, armoured cars and imposing branding. Niepokólczycki told me that Neo-militarism is rooted in the wealth of corporations. “They could afford those corpo ‘castles’ over the Night City landscape that really brandished the Neo-militarism style like a weapon,” he said.

Neo-kitsch, meanwhile, represents the ultra-ultra rich who can afford such rarities as real wood and animal leather, natural materials that are exceedingly scarce and definitely not disposable in the climate-ravaged world of Cyberpunk 2077.

Heritage preservation in North America has historically focused on preserving buildings, not communities. Santa Fe, New Mexico is famous for its pueblo revival-style downtown where the buildings have rounded corners and stucco walls like something out of Star Wars’ Tatooine. It’s an impressive place to be as a tourist, but this stagnation has led to a city centre that feels like a theme park, a Mickey Mouse version of historic Santa Fe where the cost of living has forced locals to move away while rich out-of-towners stay in AirBnBs and gawp.

Perhaps we could learn something from Cyberpunk about codifying our architectural styles in ways that relate more to community than cornices. That’s not to say we should design cities like Night City and designate parts of them as entropic, but we should avoid attempting to freeze an area in time. To its credit, the city of Toronto is starting to recognise this. Heritage planner Tatum Taylor is working on the lively Kensington Market neighbourhood and told the Globe and Mail’s City Space podcast (for which I am a senior producer) that “If we were to freeze Kensington Market in time, we would actually be losing what's most important and unique about it.”

In the 1920s Kensington Market was a hub for the city’s Jewish community. Subsequent waves of immigration from all over the world created a layered and vibrant place bustling with stalls. “You can see the accumulated layers of history within the actual built fabric,” Taylor told City Space. “There are former residential buildings that still have little gables or even half gables peeking up over the roof line of a commercial addition, and that really tells the story within the streetscape of a community coming together in a part of the city to pursue a life for themselves.”

When he wrote Neuromancer, William Gibson was living in Vancouver. He’s an American who ended up on Canada’s west coast after dodging the draft in Toronto. Most cyberpunk authors are American or British and were publishing between the 70s and 90s. Their idea of a dystopia is informed by that 20th century aversion to urban density.

Nowhere is that cultural context more apparent than in Cyberpunk 2077’s the eastern neighbourhood of Santo Domingo, described in the game’s art book as

a failed attempt to create a suburban utopia of single-family dwellings… verticality abuts sprawl, factories and power plants sit right next to supposedly idyllic residential neighborhoods and the whole urban planning concept of separate functional zones is flipped the bird.

To Niepokólczycki Santo Domingo represents the fears that many North American city dwellers have about Japanese-style inclusionary zoning. “In Night City you see that clash of different zoning as a direct effect of corporations wanting to have more of the city for themselves. And if there’s no other space to put a power plant, then fitting one next to Rancho works — but it’s never going to be pretty.”

To the original creators of Night City, this mixed use zoning is a dystopia – and nobody really wants to live next to a high-polluting industrial plant. The single family homes are depicted as dilapidated, occupied by some of the city’s poorest. The cauldrons of industry dominate chunks of land with grey pipes and corroded silos.

“For the residents of [Santo Domingo sub-district] Rancho Coronado, consumerism is everywhere — with big adverts plastered all over, even in backyards,” Niepokólczycki told me. “That's partially the dystopia: there is no escape from the meat grinder that is Night City.”

Certainly the urban planning orthodoxy of real world cities in the 50s and 60s was that cities should have a central business district, or a meat grinder if you will, which could then be escaped by car to a perfect, protected home in a suburban development. But in reality, mixed use zoning isn’t a meat grinder.

There is only one type of Japanese zoning that is exclusively industrial. There’s also commercial zoning, which allows for small factories, and quasi-industrial zoning, which allows for homes and shops. These types of zoning don’t create artificial barriers against the construction of homes in places that might actually be nice places to live, and so housing in Japan is much more affordable than in Canada. This isn’t because Japanese urbanites are crammed into the space between smokestacks and tire factories – not all industries are high-polluting collections of smog-churning machinery. I grew up near Carlisle, a British city that is often blanketed with the rich smell of cooking chocolate from the cookie factory in its centre. Mixed-use zoning allows more where it's necessary and desirable, but under the exclusionary zoning of almost every city in today’s English-speaking world, the apartments and townhouses nearby could not be built.

If Night City were made reality, those dilapidated detached homes in Rancho Coronado would be multimillion dollar pieces of prime real estate, a rare opportunity to own a detached house with your own yard in a hyperdense metropolis. The real meat grinder would be the traffic on your commute if you lived elsewhere. In a city like Toronto industrial zones aren’t places you linger unless you’re working there. When I pass by a lubricant plant on one of my regular bike rides I speed up, trying to avoid breathing the air. The lubricant plant serves a purpose, but it's kept on the city’s outskirts for a reason.

In Night City there is one purpose: play. Industrial areas are open to the player, and often the site of a shootout or stealthy break-in. The surveillance cameras are tools to be hacked and turned upon their owners. The commute is immaterial: driving is fun in Night City. Traffic has been massaged into an entertaining obstacle to swerve around, and if you screw up and crash your car it’s no big deal.

We can’t let citizens loose with throwing knives and rocket-propelled grenades in the lubricant plants of Toronto, but we can ask how we could invite people to explore more of the city. Which spaces are underused, and how can we incentivise municipalities and private landowners to go further than just allowing public access, but encouraging it with places to sit and things to do? That could include allowing retail in more places, but it's broader than that. Cities are bad at allowing life in general. No loitering.

Why do I so often find myself wondering “am I allowed to be here?” when walking through open space in Toronto? Why do we have to check what is allowed, rather than assuming most things aren’t?

Many North American cities are actively hostile to street life. In 2024 the council in my own city of Toronto voted against allowing small business in residential neighbourhoods. A cafe on the corner of my street is apparently one step too close to the dystopian hellscape of Cyberpunk 2077.

When I leave my Night City apartment in Megabuilding 10, it isn’t the presence of mixed retail on my floor that I find dystopian. It’s the smoke that chokes the view from my narrow window, the layers of highway that dominate the space between buildings, the elevator pumping out abrasive commercials selling sex, cyberware and sedatives. They remind me of the ad-laden screens in Toronto’s condo elevators, though those commercials are decidedly tamer.

Night City isn’t even immune to gentrification: that old club where Reeves’ character Johnny Silverhand used to play concerts has turned into a brightly-lit ramen chain by the time you get to check it out.

When I asked if there was anything that real cities can learn from Night City, Niepokólczycki was humble. “No, I would not go that far,” he said. “The only rules were the ones that we put on ourselves — which are totally different from the regulations a real, evolving city has to follow.”

I would argue that municipal regulations are also a set of rules made up by people. Many of them are sensible, and keep us safe – fire codes, for example. Others are more arbitrary, such as Ontario’s recently enacted law that stops cities installing bike lanes where a lane of car traffic would be removed.

If we want our cities to be more than just functional – if we want them to be fun – we should take a long hard look at the rules and regulations that govern how we build and evolve those cities. I think we would find many of them are getting in the way of creating places that we can truly live and play in.