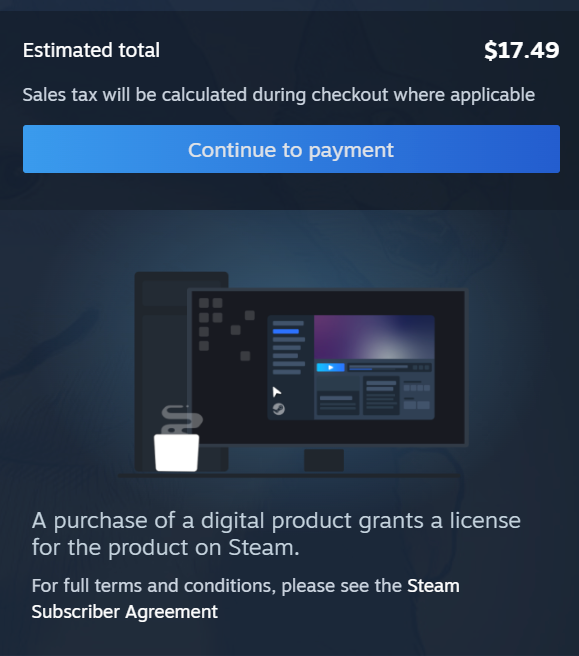

A GameStop customer, Jake Weber, is suing GameStop for alleged violations of California's digital goods transparency law. AB 2426, which was signed in 2024 and went into effect in 2025, requires companies to let buyers know that they're not purchasing video games and other digital stuff outright, they're merely licensing them. It's why Valve changed its purchasing page in 2024 to include a little note under the "Continue to payment" button: "A purchase of a digital product grants a license for the product on Steam."

Weber and his lawyers, in the proposed class action complaint filed Jan. 8 in California, say GameStop doesn't do that. The important thing to know about this law is that it's not really changing the fact that a customer is licensing and not buying a game outright; it's just requiring that storefronts be upfront about this sort of thing, which has been an issue gamers have been rallying around for some time. As games age and player bases dwindle, game publishers may decide to stop supporting a video game. For older consoles, that's fine: The game you got on the cartridge is what the game is and always will be. But as the internet became more available, and online multiplayer and live service became a thing, there's a problem. If a publisher turns the servers off, people who purchased the game can't access it anymore.

This is what happened when Ubisoft shut down The Crew in 2024. As an online-only game, people who purchased even the physical disc no longer had access. A group of gamers sued Ubisoft in 2024 over it—and the ensuing public outcry over the shutdown inspired the California law itself.

Weber's GameStop complaint outlines the situation with The Crew and the creation of California's Digital Property Rights Transparency Law. It also includes screenshots of the process of buying a digital game from GameStop, including the store page for Pokémon Legends: Arceus, the shopping cart, and checkout. Nowhere on the pages does GameStop note that players are buying a license and not the game itself, according to the lawsuit.

"At no point prior to the purchase is the consumer ever put on notice, in plain language, that the video game he is buying is just a license that can be revoked at any time," the lawyers write. "Nor is the consumer ever required to provide an affirmative acknowledgment that he or she knows the limited property rights he or she is receiving with the purchase of the digital video game."

Aftermath has reached out to GameStop for comment.

Weber and his lawyers are asking the court to grant the lawsuit class action status, so that other GameStop customers can join. It's also looking for a jury trial and damages for the impacted parties. Since the law went into effect in 2025, both Apple and Amazon have been sued for alleged violations. Both those lawsuits are ongoing.

Looking at Ubisoft's The Crew lawsuit for any indication of how Weber's GameStop lawsuit may play out, there's not much to glean. Though the proposed class action suit garnered a lot of attention, it didn't even reach official class action status. (These lawsuits are filed as proposed class actions; a judge must determine that it meets several requirements.) The lawsuit was voluntarily dismissed by the plaintiffs in June.

Regardless, the debacle of owning games versus licensing them will continue to be an issue as game developers and publishers stop supporting their old game servers. Electronic Arts and BioWare's online multiplayer shooter Anthem, for instance, went offline on Jan. 12. The issue is at the core of the Stop Killing Games initiative, which self-describes as "a consumer movement started to challenge the legality of publishers destroying video games they have sold to customers." More transparency around buying versus licensing is good, but that's not what the Stop Killing Games movement wants—it wants publishers and developers to implement "end-of-life" plans for games, so that online-only games without support can still be run offline.