For all its melodramatic brilliance, the Yakuza/Like A Dragon series has long carried a recurring blemish—substories and mini-games that veer from campy charm into outright cringe, usually involving real-life adult video actresses in awkward, fetishized scenarios. It’s the kind of thing fans have learned to grin and bear, knowing it’s a part of the series’ whole deal in the same way shonen anime always have a pervy mentor character traipsing about. Now, Kiss or Die, a Netflix variety show, takes that very same “scaring the hoes” energy and blows it up into a full-blown improv reality TV show, rife with an uneven tone, secondhand embarrassment, and a surreal sense of a Yakuza pitfall breaching containment into something with more valleys than peaks.

Kiss or Die is best described as a show within a show that’s part improv drama, part live reaction, and all cringe. Its premise sees professional Japanese comedians ad-lib scenarios in which they must resist kissing AV actresses. Meanwhile, a panel of celebrity guests and a live studio audience watch and react. If the comedians give in to a cheap kiss before becoming an ideal protagonist, their character dies. The result, at least on paper, is a surreal mix of comedy and drama where the comedians are dropped into plotlines that ask them to become heroic protagonists by resisting seduction. What I found most jarring about watching Kiss or Die’s six hour-long episodes, broken into three acts of two episodes each, was that it so neatly fell into the same pitfalls that have plagued Yakuza, which threaten to spoil the series like a rotten apple, and are long overdue for a callout.

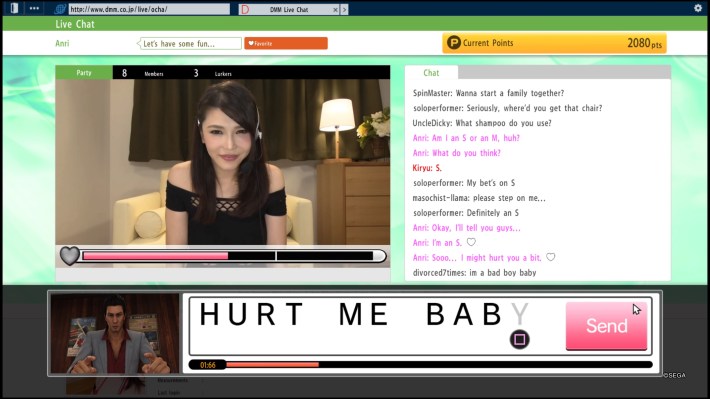

While I love Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio’s Yakuza/Like a Dragon games—especially its recent stretch of releases—every entry has one glaring segment that teeters between cringe and camp. The hostess club minigame in Yakuza 0 and Kiwami 2? Camp. The AV live video chatroom in Yakuza 6? Cringe. The dating sequences in Judgment and Like A Dragon? Teetering on the edge. RGG Studio has long leaned into the spectacle of scanning real-life AV and gravure models into their games, often as themselves, and dropping them into a substory that feels like a separate genre entirely, even to the games’ most absurd side quests. From Aika to Anri Okita, to Rina Hashimoto and Hikaru Aoyama, these actresses and models appear in minigames where players are tasked with playing dress up, snapping creep shot photos, or chatting in livestreams that unlock more risque one-on-one personal videos if players “perform” well enough.

These segments are rarely plot-essential; still, they’re often something players will either goon unabashedly or avoid because of how weird they are. The worst offender, however, is Pirate Yakuza In Hawaii. Despite centering on fan-favorite Majima, it features a substory so cringe-inducing that it demands you put the controller down and endure a series of live-action dates gone wrong, featuring AV models and Twitch streamers who auditioned to be in the game, which lasts nearly an hour.

What made those Yakuza quests painfully cringeworthy wasn’t their sexual content—the series isn’t puritanical, and that’s part of what makes it charming as a drama-meets-comedy mafia game. It's their one-sidedness. The actresses, especially in later entries, are fetishized for wish fulfillment without the give-and-take and chemistry that make for good comedy or romance. Even more, the newer Yakuza games’ use of live-action footage of the models and actresses worsens the tonal whiplash in their substories, particularly since the footage mirrors the girls' movements in cutscenes, which are similar to visual novels, where floating text boxes for players trigger stitched together scenes where the women read out lines and writhe like characters in a poorly-written eroge dating sim.

Earlier Yakuza games depicted women as in-game character models interacting with heroes Kazuma Kiryu and Ichiban Kasuga, at least placing them on equal footing with the player as characters in the same medium, rather than as real-life girls talking to the player. There’s a buffer, a kayfabe even. And the ones that aren’t creepy, like Ichiban befriending Kaho Shibuya and Ai Hongo and recruiting them as goofy members of his pirate crew, or Majima and Kiryu befriending Aika in their quest to rule the hostess club scene, are some of the best bits in their games that I would ignore the main quest for, and which others have written phenomenal essays about.

You can imagine my surprise when the monkey’s paw on my long-held wish for one of Yakuza’s minigames, like the hostess club, to spin off into its own thing. Instead, the worst part of the series’ gravure AV fetishism breached containment and manifested in Kiss or Die, a series that lacks the tact to be a competent drama or comedy almost entirely.

Much of the show resembles a bad J-drama and porno script, with potential for some good situational comedy. Its first act is a tired office new hire setup that’s emblematic of the show’s self-aggrandizing cringe. Aside from being creeped out by the clichéd power dynamic of fish-out-of-water comedians having pretty women throwing themselves at them, the show fails at its own premise by not even being an entertaining manifestation of it.

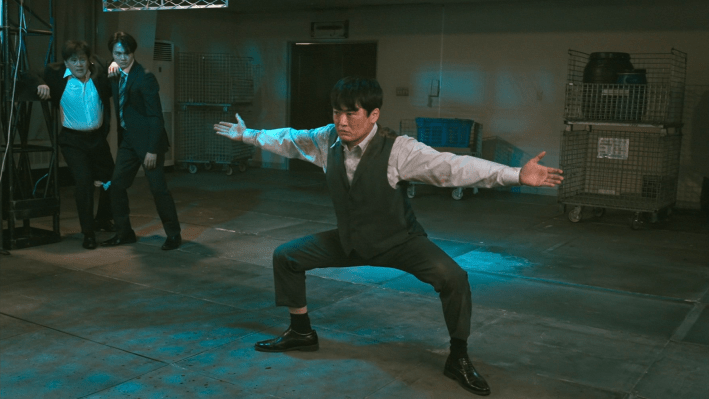

Whenever the rotating cast of comedians aren’t outright sabotaging the quality of the entire improv setup, leaving the actresses in a bind to play off them and at least make the best of their ad-libs, they’re either ruining scene setups by breaking the fourth wall, routinely calling out how stupid the show is, or, worse yet, using it as an excuse to be creepy toward the girls—turning potential good improv into cheap kisses that aren’t worth the show’s production or the high-brow Japanese actors they’re trying to bring credibility to the series with, like Tokuma Nishioka, Susumu Terajima, and Mamoru Miyano from Death Note, doing their best to carry the show’s ad-libbing on their backs.

Meanwhile, Kiss or Die’s relentless commentary from hosts Miyu Ikeda, Ken Yahagi, and Ryota Yamasato of Terrace House fame only undermines the actors for not playing along or breathlessly praises unearned scenes for being improvised. The one-note joke of comedians playing chicken with AV actresses quickly becomes old and overused, with increasingly lazy setups and repetitive bits aimed at trying to flirt with the comedians. It’s more painful to watch than an intentionally bad but funny moment, especially in its miserable second act.

So why watch six episodes of an unremarkable show I’ve written off as Yakuza eroge slop? Because, against all odds, Kiss or Die managed to eke out one saving grace—the improvisational brilliance of comedian Gekidan Hitori. His presence alone kept Kiss or Die from peaking too early and its finale from collapsing into a total crapshoot.

To my surprise, Kiss or Die revealed one glimmer of promise across its six episodes in its scenes between AV actress Nana Yagi and Hitori. While most pairings devolved into awkward skits with comedians either mugging for cheap laughs or trying to bait their scene partners into even raunchier territory, Hitori did the opposite. He dove headfirst into his character—a foolhardy CEO—and played the setup straight (or as straight as a comedic premise would), riffing off Yagi’s timid responses about liking books while she was blowing seductively in his ear. Instead of ignoring the ad-libbed prompt from Yagi, he would play off of it, interrupting her seduction with an impromptu timed presentation exercise to work on her shyness. Instead of breaking kayfabe by drawing attention to the show’s absurdity or forcing his scene partner to be even more lewd than the show called her to be in a scene, he built continuity.

That setup paid off brilliantly in the show’s most absurd twist: the women were all poisoned by a mysterious figure using them as weapons to trigger the comedians’ superpowers from their orphaned years. Apparently, the only way to activate their powers was through prolonged frustration, culminating in emotional and physical catharsis from a true love kiss. This kiss also served as a poison neutralizer, provided it was born from genuine love. While the other comedians phoned in weak justifications for their cheap kisses, Hitori brought back the earlier presentation motif, asking Yagi to list the things she loved about herself, saying, “You can’t love someone if they don’t love themselves first.” It was the only stroke of improv genius in a show predicated on its comedian’s ability to ad-lib, and it fucking landed.

Everything else was a rinse-repeat cycle of cringe so grating that even the panel’s token female reactor, Ikeda, voiced her exhaustion of the rest of the show dragging on. Whenever Hitori wasn’t on screen, I was asking, “Where is Gekidan Hitori to right this sinking ship?” His theater chops and directorial instincts elevated every scene, pulling his co-stars into his orbit and giving them something actually to play off—not just endure—when the show finally dialed down its tired seduction farce and leaned into actual acting from all parties involved. With Hitori as a lightning rod, the rest of Kiss or Die’s cast started yes-anding each other, playing off cues, and delivering impassioned rebuttals that felt earned.

No doubt, Kiss or Die, much like Yakuza, swings wildly between entertaining and insufferable. Its second act is especially rough, bogged down by convoluted plot points that should’ve given the cast more to chew on but instead exposed their limits. Yet through all the tonal whiplash and cringe, Hitori emerged as the show’s undeniable MVP, delivering the kind of clutch performance the series desperately needed.

Kiss or Die ends on a tease for a potential second season. If that happens, I hope we get more Hitori as its leading man, and that the series learns from its plentiful misfires and builds something that leans into its rare highs while trimming the many lows that dragged it down.

![Adobe Is Ruthlessly Killing Off Software That Animators Around The World Are Using Every Day [Update]](/content/images/size/w30/2026/02/Untitled-1.jpg)