Sometimes, on my better days, I think I know the answer to what keeps me up at night. Or that I have it in me to figure it out. I like those days because even though they start with a problem, I know where to go, what to do, or who to ask to solve it. That's a pretty good day. Not too many of those lately.

Perhaps this is why, when considering the year that was, mysteries – particularly video game mysteries – come to mind. Of all the entertainment released in 2025, I was drawn to these the most: I know the dirty secret of the Roottree family. I know why Evelyn Deane disappeared from Blake Manor. I know the truth about Mt. Holly Estate. Some questions wormed into my head, and I answered them. I had problems, and I solved them.

When executed well, sleuthing suits video games even more naturally than violence, a contest between the programming logic of video games and the human ability to think laterally. One of the first things you learn about coding is that computers are literal to a degree that is, frankly, madness-inducing. The genius of any particular application, including video games, lies in how elegantly it hides the fact that it is reducing your every input into a cascade of simple binary decisions. However, even with a program designed to do all of the heavy lifting for you, even with all the cumulative experience of the internet at your disposal, sometimes the thing that lies between you and your goal is the wildly frustrating task of figuring out how to ask the right question.

This also happens to be the engine that drives a good mystery.

On a basic level, a video game mystery narrativizes one of the most fundamental computational functions: Querying a database. (The narrative designer Bruno Dias has called games expressly built around that function "database thrillers" for this reason, going so far as to jam out his own – quite good! – text parser version of one, Kinophobia.) Defining the right parameters that will separate the endless sea of useless data from the precious and narrow set of information you can actually use, perhaps to form another query in turn, rendering previously useless data into something vital. Once again: Asking the right questions.

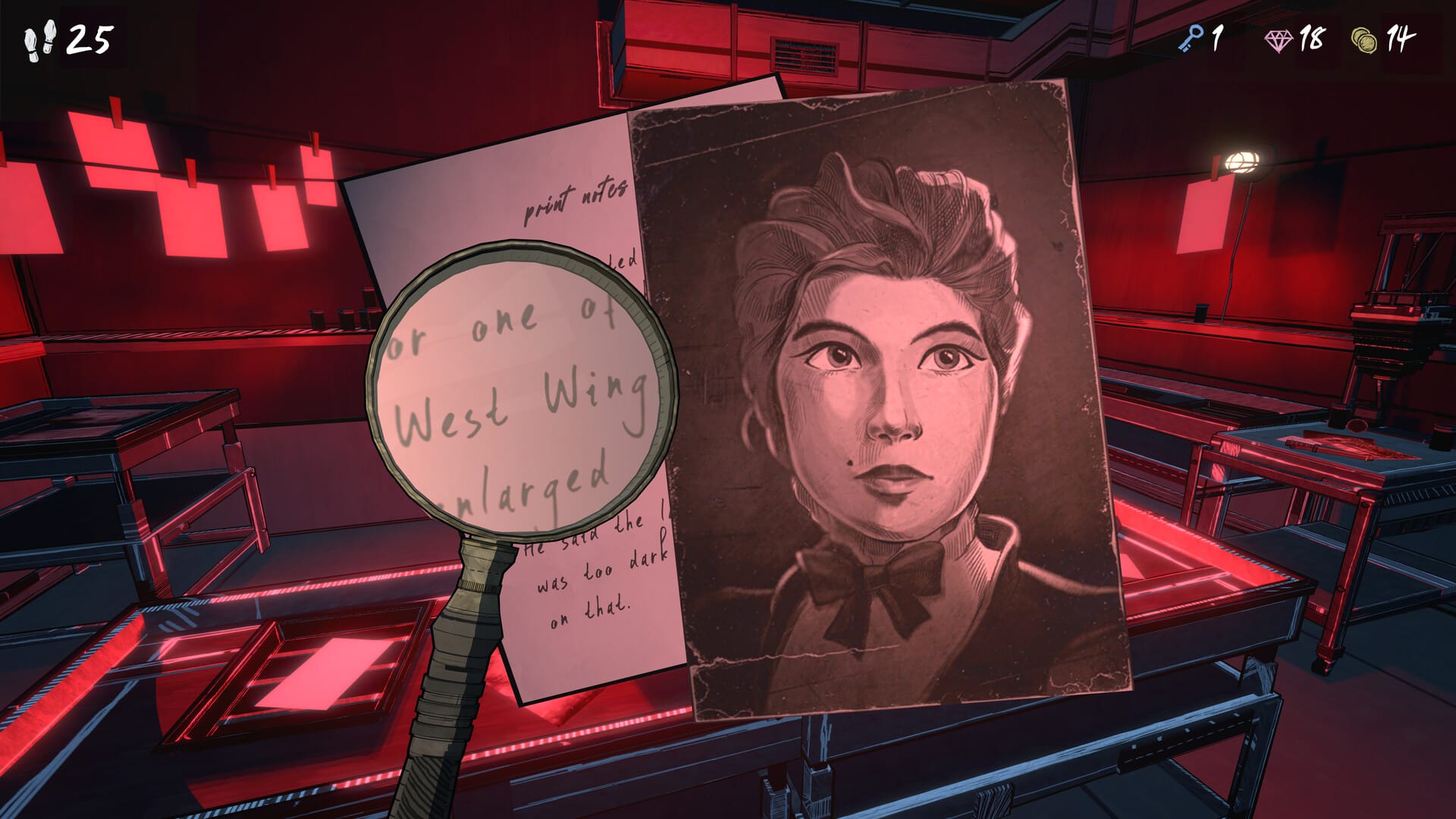

The Roottrees Are Dead, Jeremy Johnston and Robin Ward's 2025 remake of Johnston's browser game of the same name, operates on this fundamental level. It casts the player as an amateur genealogist, asked by a mysterious client to trace the family tree of the Roottree sisters. Recently deceased in a private plane crash just before the start of the game, the sisters are heirs to a massive family fortune, and their untimely demise means a significant windfall for the extended family.

The pleasures of The Roottrees Are Dead lie in doing the task it sets out for you in its simulated tactility. The game is set in 1998, and in researching the Roottree family, the player bounces between a table with relevant documents and photographs to examine, a corkboard where they lay out the family tree, and a desktop computer with a blistering 56k modem for surfing the information superhighway. A notebook, available at the push of a button, allows you to type notes or collect highlighted passages from your research materials. Using all these tools, a family's history becomes a giant jigsaw puzzle, a deductive riddle that feels impossible until you just buckle down and do the work. One good lead yields another, and then another, and finally you have names and faces and the puzzle begins to take shape.

But these aren't just puzzle pieces: They're people. The connections and if/then questions that determine where they fit in the Roottree pedigree are just part of the story. What makes The Roottrees Are Dead such an exceptional game is in the way it tells you from the start that one branch of the family tree is off-limits until the end, an optional question where the answer isn't so much there to be found as it is inferred. In laying out the endgame this way, Johnston and Ward provoke the player: Were you merely solving the puzzle? Or were you paying attention to the story it told? You know the what – how about why? Can you see the people hidden between the data points?

In the twilight of the 19th century, the massive disruption of the industrial revolution left European high society in a state of unease, as the edges of a carefully-constructed social order began to crumble. Literacy spread among the middle class, the world shrank as steamships sent people all over the globe, new customs and experiences shook the once–strong foundations of Christian institutions. For many people of means and those who aspired to such status, the church was insufficient at addressing their moment of malcontent. The occult took root.

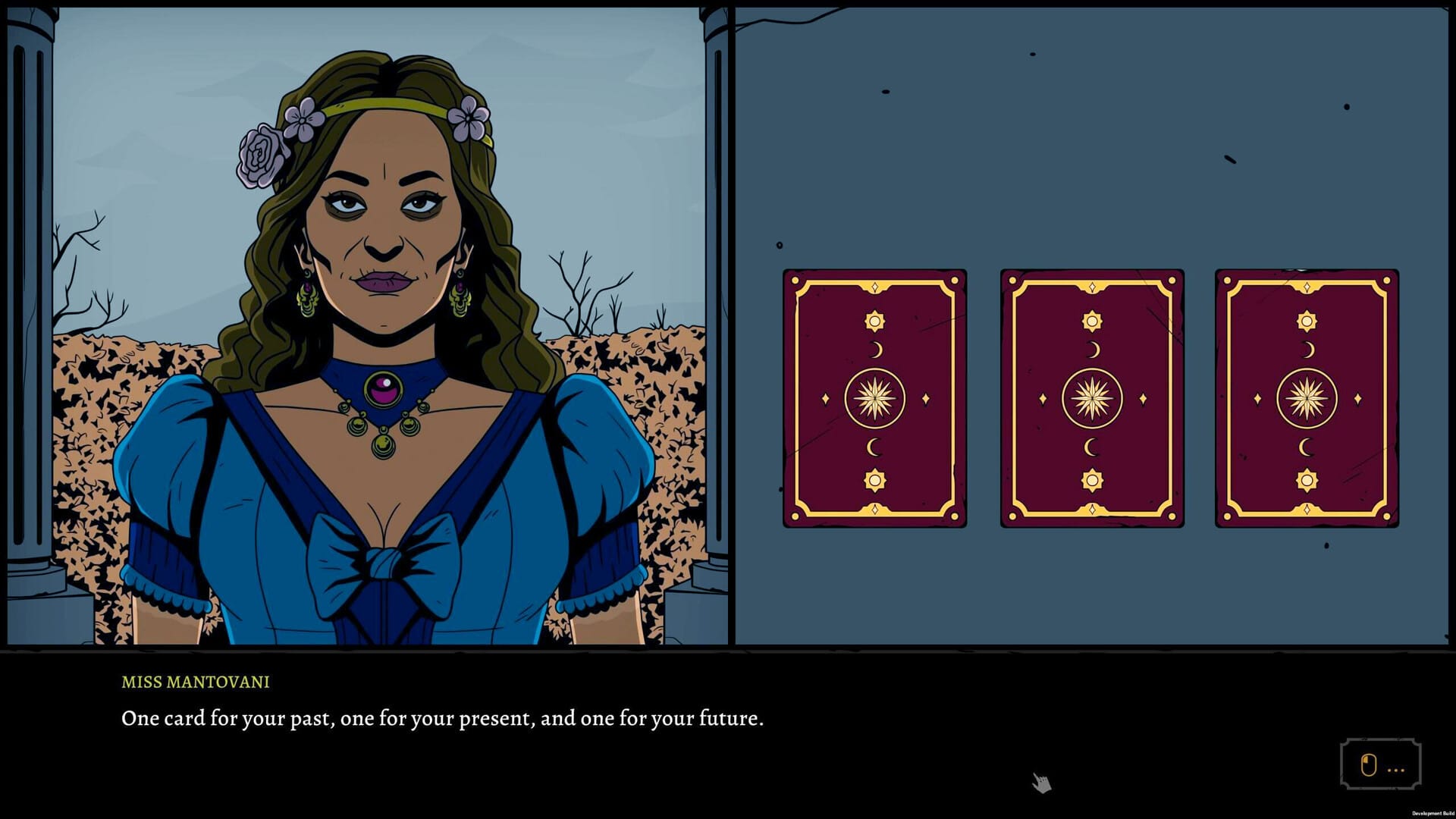

Set in the final three days of October 1897, The Seance of Blake Manor follows Declan Ward, a detective from Dublin, after he receives a mysterious commission to investigate the disappearance of Evelyn Deane. Deane was one of a number of mystics and magic-curious from all over the world invited to Blake Manor, a hotel in Western Ireland, for a Grand Seance to take place on Samhain, the day when the veil between the mortal world and the spirit realm is thinnest. Assuming the role of Ward, the player wanders the eponymous manor, snooping through rooms and asking guests questions, each exchange or observation deepening the mystery of Ms. Deane's disappearance.

The Seance of Blake Manor is a work of folk horror, which means that history has something to say here, whether the story's characters are able to hear it or not. (They will pay if they don't.) While a far more traditional narrative than The Roottrees Are Dead, Blake Manor is similarly powerful in its subtext. Every character is haunted by some private thing that has brought them to the seance; each is fleeing something or in denial or mourning or desperation. It causes them to be cruel, selfish, reckless. You can piece these backstories together for as many characters as you wish – the game encourages you to solve them all – but what lingers for me is the weight of all that history.

In the search for Evelyn Deane, Declan Ward must repeatedly contend with the beliefs of others. He learns much about Irish folklore, of the fae and the Other World and the Tuatha Dé Danann, the pagan deities worshipped in Gaelic Ireland before Christianity arrived in the country. He sees evidence of the ways both Catholics and Protestants have incorporated those pagan traditions, turning them into saints or holy days. He meets people from around the world who have their own version of those same saints and gods.

Blake Manor requires you to note all this, and think about it some. Learning the faith of each character you meet is integral to solving its mystery. But in this story, Christ and Allah are both just characters in books. The pagan deities, however, are very much real.

I don't believe this is the game choosing a side, asserting that the pagans had it right and everything else is just a fairytale. Rather, I think The Seance of Blake Manor's choice to slowly, deliberately communicate that, in its fiction, the folkloric deities are real is meant to underline the ways in which the indigenous beliefs and cultures of a place are never really gone, even after waves of colonization, industry, and plunder. The spirits are real in Blake Manor because we have fooled ourselves into thinking that wealthy men who build monuments to their fortunes and family name are the only ones who get to write their stories upon the land, forgetting that the land might have stories of its own. Will you seek them out, even if you don't have to? Will you carry that history within you, and keep it alive just a little while longer?

Like many others this year, I have lost countless nights in search of the secret 46th room in the Mt. Holly Estate, and for the bewildering number of mysteries Room 46 is but a mere prelude to. I have many of the answers I set out to find, but I still have further questions beyond them. I also know that the point here may very well be learning to quit.

It's remarkable that Tonda Ros' Blue Prince is structured as a roguelike, a genre defined by its endlessness and infinite possibility. This brings the game in conflict with its narrative setup, which casts the player as Simon P. Jones, a young boy who has learned his wealthy uncle has willed his entire estate to him – provided he can find the hidden 46th room in the logic-defying 45-room mansion that changes its layout every day. Such an explicit goal implies an ending, and upon achieving it, credits do roll. But as anyone who has played Blue Prince knows, that ending is merely an ending. It is also not a solution. Simon's strange quest, the magical nature of the house – which, after enough excursions, is clearly diegetic and not just an allowance for gameplay – are the first of many whys that are left unsaid by that initial ending.

Thus the real mystery of Blue Prince begins, but what that mystery is largely depends on the player. What about this house and the family who built it did you notice, or care about? What in its many possible configurations, its hidden foundations, its many scrawled notes that double back and recontextualize previous findings, bedevils you? Is the game truly endless, like its genre structure implies? Can you be at peace with that? Or do you refuse to accept it?

Consider again how well-suited games are for mystery, how they can present players with impossible enigmas but also guide and nudge them towards asking the right questions. Games can assure players that the world is knowable. We talk about power fantasies, and perhaps this is the most seductive one, even more so than those that give us guns or impossible abilities or great destinies. The fantasy of a world that fits together.

I find that fantasy alluring. Justice has been lacking in my lifetime, and it may not be my lot to see it win the day. I like the idea that asking the right question is the first step to making sense of the world. And if I ask the right question and then answer it skillfully, I can find some kind of peace. Or at least, know what it is that will give me a direction to walk until I find it.

This is a delusion, but a useful one. Answers aren't what make questions worth asking, but go long enough without finding your way to one and, well. That's a lot of sleepless nights. Sometimes you need a ballast.

If there is a reason these games are the mysteries that have resonated with me most strongly this year, this is why: because while they provide all the pleasures of a solvable problem, of crimes answered for, they also present me with so much I cannot know. Of how much escapes the record of material evidence in the gaps of a family tree or a nigh-forgotten folkloric tradition or the inscrutable patterns of an ever-shifting mansion. There is tragedy in this, but also grace, and humility. In grappling with them, solving a mystery takes on another, more durable purpose: making peace with what I don't know, so I can be brave with what I do know. Every day I'm able to do that would make for a good day. Every year I strive for that goal would be a good year.