This piece originally appeared 2/12/26 at Mothership, a worker-owned outlet providing gaming coverage for her, for them, and yes, for him. If you like what you see, consider subscribing!

I've spent the four years since Bayonetta 3’s release wanting to write more about it. A big reason why I haven’t is that a lot of people hurt my feelings way back when I reviewed it upon release in 2022. I was still on Twitter back then, and despite that I’ve been harassed online many times for writing about video games, I was shocked by the amount of homophobic slurs I received in response to my review. That experience was deeply upsetting. What was also surprising, and a lot more interesting to talk about, was the response to the game from queer and women writers, who, like me, had a lot to say about the game’s themes and writing decisions. I couldn’t spoil the game in my review, nor could other critics, so I never fully expounded on why the game’s story fell flat for me and so many others. The time has come.

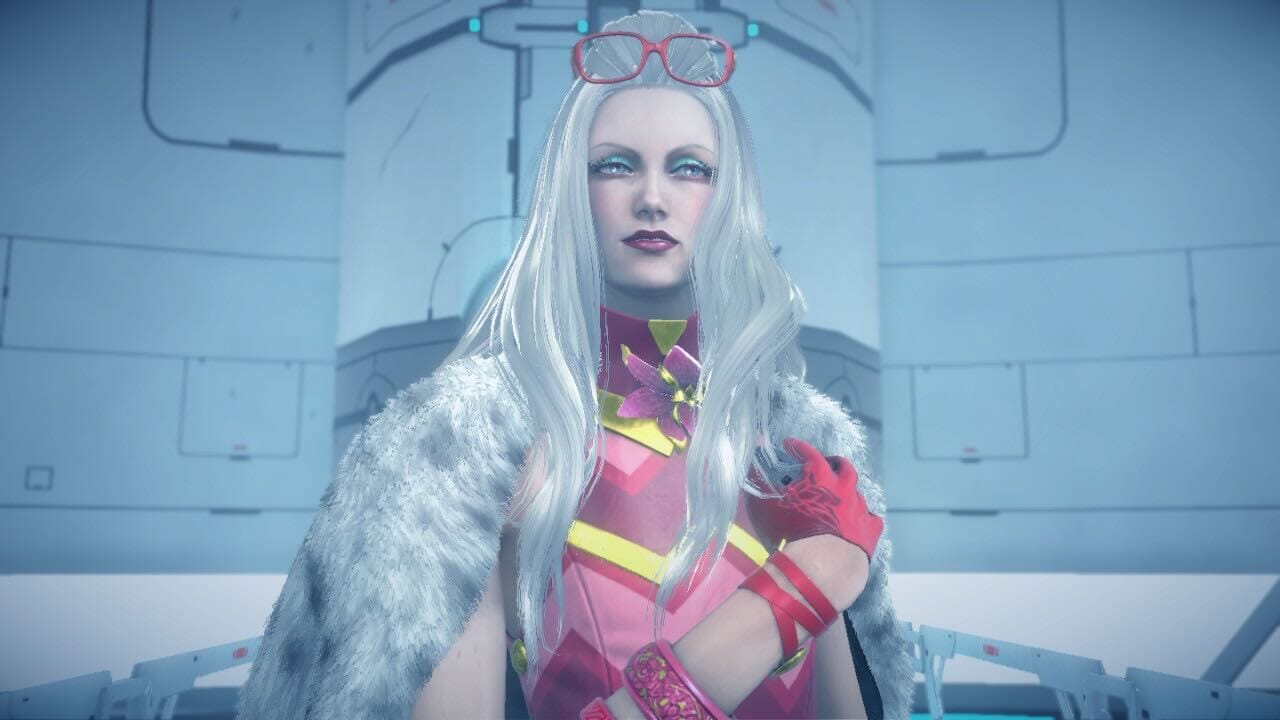

By the time Bayonetta 3 came out, the title heroine had very much become a queer icon. This was the lens through which a lot of queer fans fans saw the character. It’s easy to see why if you look at her character design. She has heavily exaggerated feminine features — extraordinarily long hair, for example, and a Barbie doll body with mega-long legs. If you create a character, any character, with extremely exaggerated feminine features (like Bayonetta, or Lara Croft) — or exaggerated masculine features (like Duke Nukem) — it’s likely that character is going to be claimed by the queer community. Thus, Bayonetta is both a sex symbol for straight men, and a drag icon. This is also why Duke Nukem can be both a hyper-masculine ideal for straight men as well as a drag king.

This creates a complicated dynamic in the world of video games, where so many characters are exaggerated in this fashion. (The same thing happens with pro wrestling, by the way.) Straight male fans often do not understand this dynamic, if they see it at all. The ones who are bigoted get scared when queer fans claim characters in this way, because it forces them to confront their own insecurities about sexuality and identity. A person who is afraid of confronting any of that is probably also very freaked out at the idea that there’s anything queer about Bayonetta, whom they see as a sexy lady meant for straight men only. Hence the response to my review of Bayonetta 3.

But Bayonetta wasn’t just a queer icon; many queer fans saw her as actually queer, in a romantic relationship with her fellow witch Jeanne. This was never actually confirmed in any game, but hopeful fans would cite examples like Bayonetta series creator Hideki Kamiya posting a poll on Twitter in 2016 asking fans to vote on the “best couple,” while listing Bayonetta and Jeanne as one of the options (they won).

It would have been cool if Bayonetta and Jeanne had ever been confirmed as a couple, even if it was something as small as “they kissed one time years ago,” but I need to be clear that I never actually expected Bayonetta 3 to do something like that. I’m a jaded millennial; I’ve lived through too many queerbaiting scandals to count. Furthermore, this is a big-budget game that was released globally, including in countries with very strict laws about queer expression. The best case scenario was that Bayonetta 3 would continue to leave the entire question unresolved, with Bayonetta remaining the perpetually single, unattainable queen who steps on her admirers’ fingers with her gun-adorned high heels.

Bayonetta 3 actually did end up surprising me — with how straight it is, especially when compared to previous entries. I’m not even talking about the relationships in the game; I’m talking about the heteronormative themes on display. This is a game that ends by referring to Bayonetta and her male love interest as very literally being Adam and Eve. It doesn’t get straighter than that, nor does it get more toxic when it comes to patriarchal gender norms. These norms actually date back to that ancient Biblical story, which has been used as a tool to oppress women for centuries. It’s surprising that a series like Bayonetta, whose previous entrants subverted Christian allegory by depicting damned characters as heroes, does away with that in Bayonetta 3 by presenting Adam and Eve as an idealized love story. The Biblical story of Adam and Eve frames women as inherently sinful betrayers, and associating Bayonetta with the Eve archetype is a depressing rebuke of her character up to this point.

[Editor's note: Spoilers for Bayonetta 3 follow after this point.]

Bayonetta 3, like previous entries in the series, introduces a lot of metaphysical lore. Here’s a brief rundown: Bayonetta is a witch who exists in a world where heaven, hell, and purgatory are very real physical locations with their own leaders, alliances, and long-held grievances. Sort of like in the world of the Diablo games, the characters who hail from heaven aren’t necessarily “good guys,” especially because our heroine is a witch. Bayonetta is facing an eventual fate of eternal damnation, but if anything, that’s presented as a point of pride for her and her similarly damned friends. (It’s no wonder that queer fans related to that; all of us are supposedly damned, too.)

It wouldn’t be entirely accurate to describe Bayonetta as a fully realized character. She’s more of a larger-than-life persona who speaks in one-liners and can do more backflips than any Olympic athlete. This is part of why it’s hard to imagine her actually being in a couple with somebody, even Jeanne (although at least Jeanne is also a larger-than-life witch who has similar qualities). This is also why Bayonetta 3 is so confusing for me, because it ends up throwing her together with a secondary character named Luka — a human man, introduced in the first game as a journalist who mistakenly thinks Bayonetta killed his father and is investigating her. He realizes Bayonetta is innocent of that crime, and then Luka falls into the position that almost anyone would be in with Bayonetta: he worships her and lusts after her. In the first two games, Luka is presented as comic relief — or at least, that’s how I perceived it, because he hardly shows up other than those comedic moments of him begging at Bayonetta’s feet.

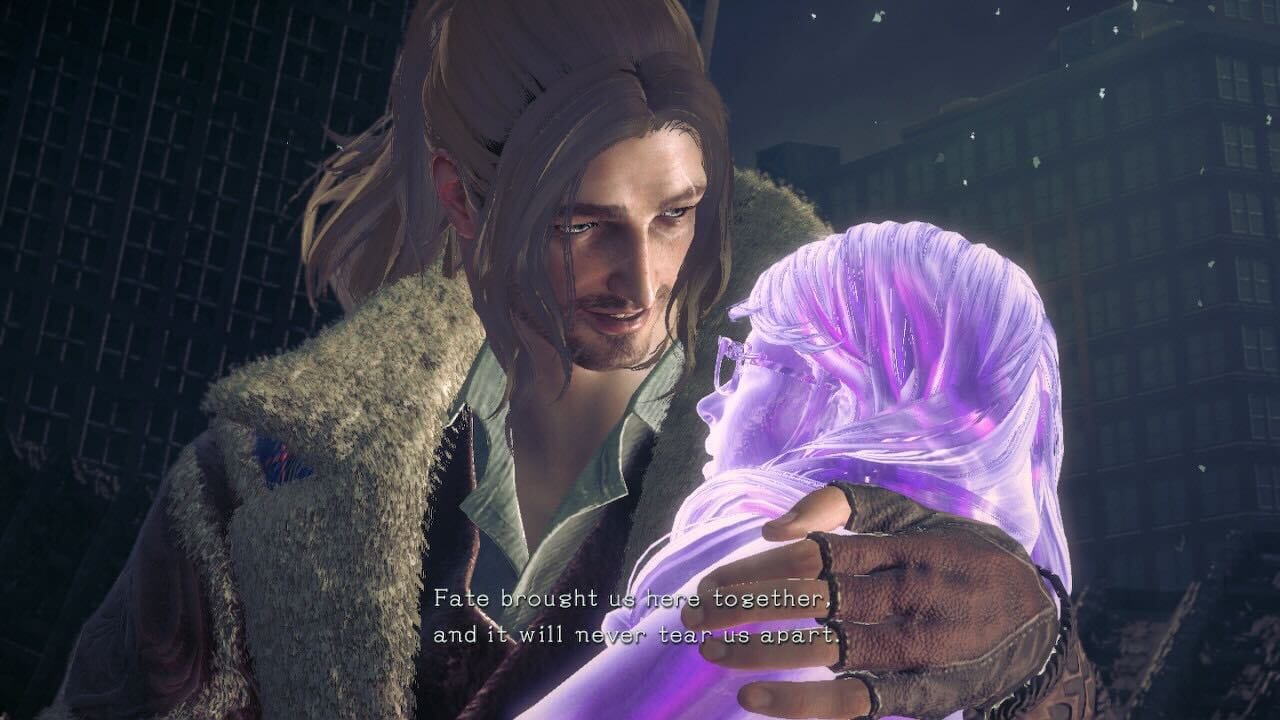

Bayonetta 3 introduces the concept of the multiverse (it was 2022, this was an unavoidable trope for some reason) and a character named Viola, who turns out to be the daughter of Bayonetta and Luka from another universe. This always could have made sense; it’s not unbelievable to imagine that, in some other world, Bayonetta and Luka might have had far more chemistry with one another than they do in the universe players know them from. Unfortunately, though, that’s not how Bayonetta 3 presents their love story. Instead, after introducing the multiverse and allowing Bayonetta to meet other versions of herself in these many other worlds, the player soon learns that apparently Bayonetta and Luka are destined to be together in every single one of these worlds. This is a strange status to thrust onto Luka, as he didn’t really seem to be Bayonetta’s one true love in any previous game, nor even in Bayonetta 3.

Of course, Bayonetta 3 could have done the work to introduce Luka in this fashion. That would have helped. Instead, the game’s writing does a massive disservice to Luka — one that I’m shocked more fans didn’t see as outright offensive. In this game and this game only, Luka gets cursed to transform into a magical werewolf, and he spends most of the game in wolf form. Bayonetta and their daughter Viola don’t recognize him in this form; for the majority of the game, he is very literally trying to kill Bayonetta and his own daughter, unable to control his werewolf strength. Eventually, it’s revealed that this werewolf creature is Luka, and he admits to Bayonetta and Viola that he can’t control the transformations and can’t help his extreme violence towards them. This is a classic gender stereotype that casts men as violent predators unable to control their impulses; wolf imagery in particular is so overused as to be a cliché. (Take, for example, the moment in the Twilight book Eclipse when Jacob the werewolf forces a kiss on Bella, who can’t fight him off due to his wolf-like strength.)

It’s shocking to me that Luka’s confession of violent impulses is part of the couple's romantic arc, and that Bayonetta ends up in turn professing her true love for Luka. To say this is a harmful representation of romance would be an understatement. All of this is leading up to the climax of the game, in which the explanation for Bayonetta and Luka falling in love in every timeline is that they are metaphysical representations of Adam and Eve. This ancient religious story is one that famously frames Eve as the sinner who dooms humanity, a framework that makes Luka seem like the good guy and Bayonetta the temptress he can’t resist. By juxtaposing this with the storyline of Luka as a wolf-like animal who can’t resist attacking her (and his daughter), this message is not just subtextual: men cannot resist their baser instincts, and women are at fault for tempting them into this… and yet women must love and forgive men for these animalistic urges, somehow.

The worst part, though, is the game’s treatment of Jeanne. She’s relegated to a series of side missions that are notably simplistic compared to the rest of the game, and she ends up getting killed in a scene that doesn’t even involve Bayonetta. She’s killed so unceremoniously that it’s hard to interpret her death as anything other than a quiet fuck-you to the fans who thought her relationship to Bayonetta might have been something more — especially given that for the entirety of the game, the once-strong and resilient Bayonetta is swooning over a werewolf man who keeps trying to kill her and her teenage daughter.

Viola, meanwhile, gets short shrift as a character as well. She’s supposed to be introduced as a new witch in training, but her combat design is so different from Bayonetta’s that playing as her is quite difficult. I ended up liking her combat design, but I had to really put in the work to learn how to use her moves, and by making her so different, the designers all but guaranteed that players would resent her. It doesn’t help that she’s a teenage girl who talks a lot, which is a character archetype that often gets maligned as annoying, even when that’s not true. I actually like Viola, but Bayonetta 3 does not make it easy. Allowing her fighting style to be more similar to her mother would have gone a long way towards helping players see her value as a new character.

Bayonetta 3 ultimately ends with both Bayonetta and Luka dying in one another’s arms and descending into hell together, as Viola promises to take on the new mantle of Bayonetta. It feels like the ultimate punishment not just to those queer fans but to all Bayonetta fans: kill off the main character and leave behind a character so different from the protagonist. It’s also a bizarre message from a feminist perspective to suggest that, by becoming a wife and mother, Bayonetta needs to figuratively lay down her sword and retire. Why can’t she keep on fighting alongside her daughter? Why, exactly, did she and Luka have to die?

Images: Bayonetta 3 (PlatinumGames/Nintendo)

I don’t expect Bayonetta (or Luka, or Jeanne) to stay in hell forever; this series takes place in a metaphysical world, after all, where escaping from a place like hell is actually viable. I think it’s pretty likely that Viola will go on a quest to save her family from their fate in Bayonetta 4 (a game that was already in the works when Bayonetta 3 came out). But now that I know Luka and Bayonetta are apparently destined to be together forever, despite how toxic their relationship seems to me, it’s a lot less exciting to see how the rest of that story would play out.

Apparently, for series creator Hideki Kamiya, this was always how the story was going to go, and I just missed the signs. Kamiya described the backlash to Bayonetta 3 as "a perplexing experience," although I’m just as perplexed that he and the rest of the writers thought fans would be OK with seeing Bayonetta die and Viola suddenly get thrust into the spotlight. The series is called Bayonetta, after all.

No matter what, though, Bayonetta 4 is going to be a very different game, because Kamiya and many other designers quit PlatinumGames last year. Kamiya founded a new studio, Clovers Inc., with several of those folks; they’re working on the new Okami game. If there is a Bayonetta 4, it will be the first game to happen without Kamiya at the head of it.

As a huge fan of the first two Bayonetta games, it’s hard to feel hopeful for what comes next, even if a completely different creative team is in charge. I don’t see a great way to retcon the Adam-and-Eve framework for Luka and Bayonetta, and it’s something that’s hard for me to get past. Although I’ve always seen Bayonetta as more of an untouchable and unattainable single lady, if she were to end up with a love interest (of any gender), I would have much preferred to see a healthier relationship dynamic than the one that Bayonetta 3 presents. (When it comes to the male characters, I'd say she has a lot more chemistry with weapons dealer Rodin than she ever did with Luka.)

There were much better ways to write the story of Bayonetta 3 — I’m partial to this rewrite done by Reddit user CourierEight, as an example — but instead, we’re stuck with the one we got. All I can say is, I wish good luck to anybody trying to clean up that mess and make Bayonetta 4 a decent story for a heroine who always deserved better and still does.

Mothership is a website, a channel, and a community co-founded by Polygon veterans Maddy Myers and Zoë Hannah, where staff and freelancers cover how gender and identity relate to games.