In “Planetary Consciousness,” Alan Moore’s introduction to the 2000s DC comic Planetary by Warren Ellis, the legendary author didn’t just herald a new era of comics—he forecasted a shift in their audience. “The underlying human tastes and audience demands on which we built the comic field have altered in the flux of things, within the readership if not within the books themselves. The way people think and see things has moved on. The massive scaffolding of values where the comic field was raised seems now deserted, seems redundant,” he wrote. Moore argued the medium’s evolution had stagnated, stuck in reverence for idols and stories that once redefined the 20th century. While many creators looked backward for answers, Moore praised Planetary as a rare comic book work that embodied the future by daring to interrogate the medium’s mythology while offering a blueprint for what storytelling could become in the new millennium.

Yet, hindsight, as it’s wont to do, complicates legacy.

Moore’s prolonged endorsement of Planetary—a comic nevertheless worthy of its accolades—sits uneasily beside the controversy surrounding its writer, Warren Ellis. In 2020, Ellis, who’d written for Marvel, DC Comics, and Netflix’s Castlevania series, was accused of a myriad of alleged sexual predatory behaviors by a group of 60 people. Although Ellis later returned to the comic book industry the following year at Image Comics, the question still lingers: Can we truly separate the art from the artist when the art continues to shape us?

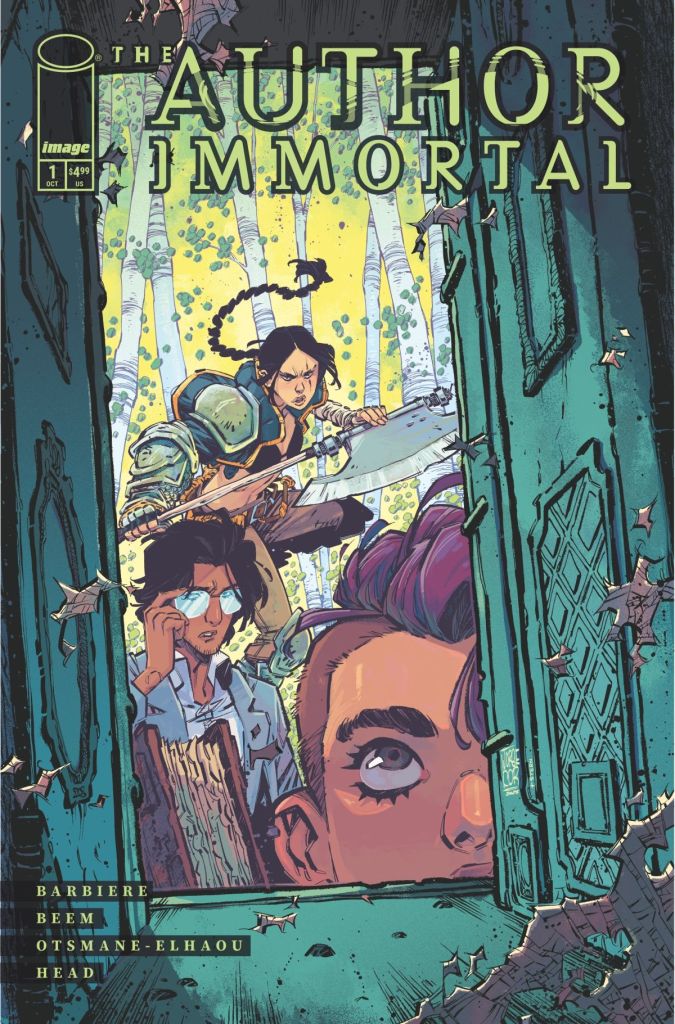

The conversation has shifted, as Moore predicted: Readers now struggle to separate the art from the artist as formative creatives like Neil Gaiman and J.K. Rowling spark debates. Former Destiny writer Frank Barbiere (Five Ghosts) and Morgan Beem (Swamp Thing: Twin Branches) confront this tension head-on in their new Image Comics series, The Author Immortal.

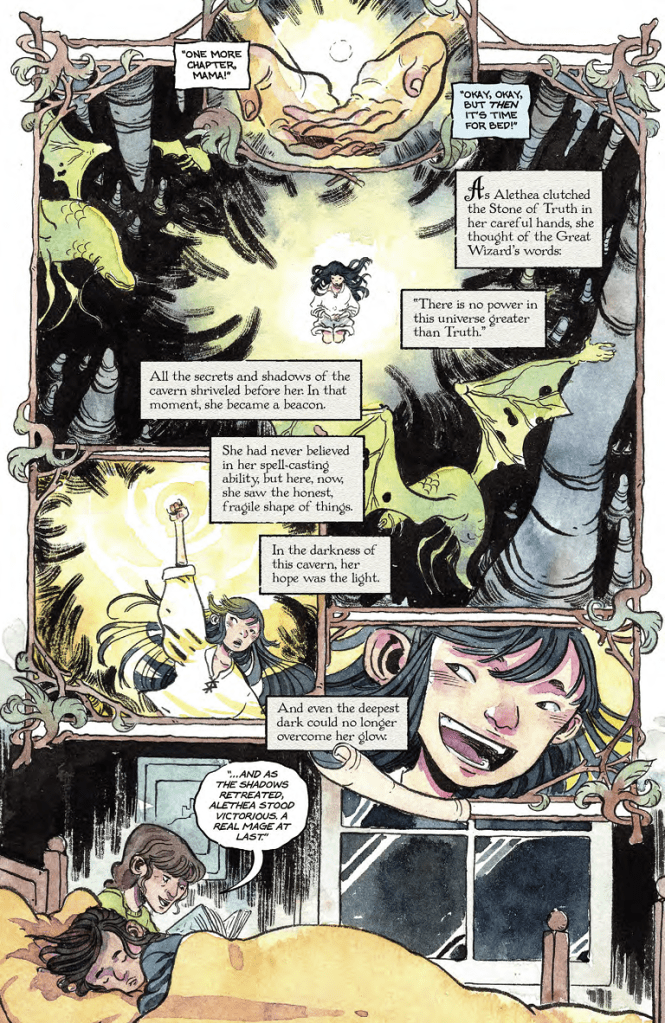

The Author Immortal tells the tale of Hector Ramire, a failed writer who stumbles upon the chance to reboot a formative fantasy children's book as its co-writer after its original author, Vossler, mysteriously disappears. After discovering that the previous author was spirited away into his own fictional world, Hector and his child, Al, are pulled into the book isekai-style. While figuring a way out, they must reckon with the sprawling world of living characters who don’t want their stories changed.

In a world where A.I. threatens to hollow out the soul of storytelling, stories are treated as disposable content with the sole purpose of printing infinite money, and formative creators’ fall from grace forces readers to decide if the art is ever truly separate from them. Beem and Barbiere endeavour not to provide a tidy answer, unpacking artistic messiness one issue at a time. Aftermath spoke with Barbiere about how he and Beem went about approaching their new comic and exploring a subject looming over not just comic books, but every facet of creative works.

Penning The Author Immortal was a homecoming for Barbiere to the comic book industry after spending his time with games as a lead writer at Skydance Interactive, writing stories for Darksiders Genesis and Ruined King: A League of Legends Story. While writing a story about writing stories isn’t novel, Barbiere found himself compelled to find his own ground with a metafiction comic that moved him like Mike Carey's artist Peter Gross’ Vertigo comic, The Unwritten—one of his favorite books of all time—had. However, Barbiere didn’t want to settle for making a poor man’s version of The Unwritten, but to put a spotlight on the eroding trust of stories with readers.

“It really began with what I think is—forgive my grandiose wording—a generational wound around fallen or cancelled authors of my generation. There are certain people, obviously, J.K. Rowling is the biggest target, Orson Scott Card was a big one as well for a lot of people, and presently Neil Gaiman,” Barbiere said. “This idea that these works that resonate so deeply with often smaller, queer communities who are typically not serviced by mainstream comics—especially when speaking of Gaiman—but also people who love fantasy and grew up with these books.

“Seeing the, quite honestly, heel turn and disgusting behavior of a lot of these people has created a huge rift, I think, in trust of fiction for my generation where it’s, ‘Oh my gosh, these books we believed in that we thought were organic and really spoke to the heart. If their writers are turning out to be these people, what does that mean for the work? What does that mean for me?’” Barbiere said.

Barbiere has no illusions that The Author Immortal will provide a catch-all solution to readers navigating these muddy waters. “The real goal for stories is for human beings to explore scenarios outside themselves to learn. Basically ‘virtual reality.’ It’s supposed to be a safe space where we can explore different feelings, personas—anything that is not real, and learn from it,” Barbiere said. “That really inspired but saddened me, considering how so many things have gone wrong and how little trusted stories are.”

Barbiere likened this current phenomenon to an article headline in which director Peter Jackson admitted that The Hobbit wasn’t his best work, which Barbiere called readers relishing tearing down the film trilogy as a validation for their distrust of the creator for being inauthentic and commercial. It’s a sentiment Barbiere senses has gotten all the more exacerbated by the pervasiveness of A.I. encroaching upon creative spaces.

“‘Can I even trust what I’m reading was written by a human?’That general anxiety led me to want to tell a story to reaffirm what stories are for, what they can do for you, how you can believe in them, and how they’re useful,” he said. “But, in doing so, we need to show the negative up front.”

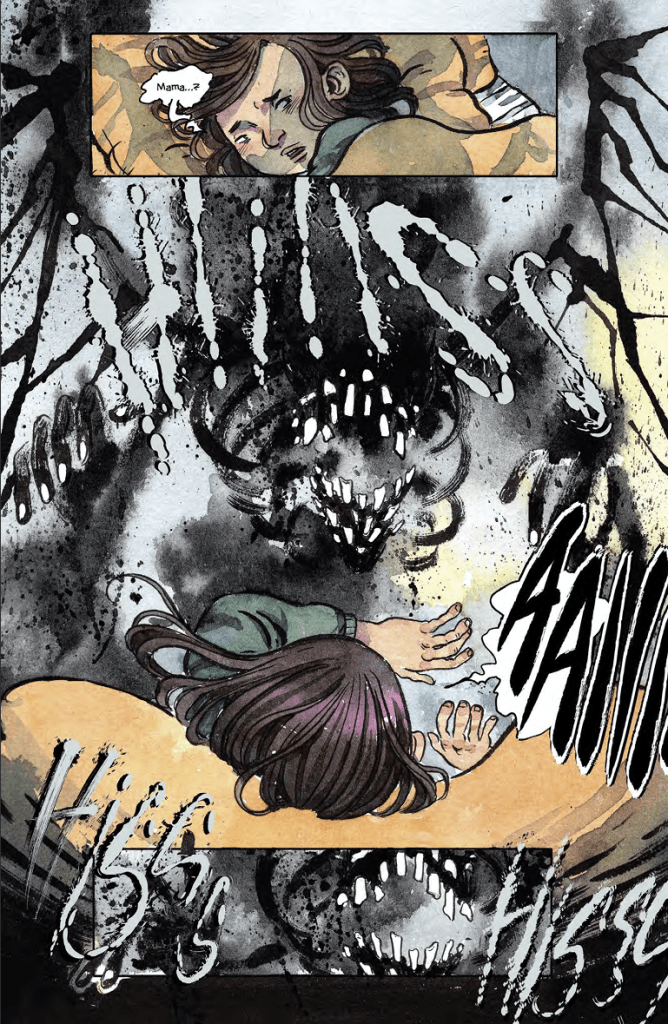

Barbiere explains that The Author Immortal confronts its charged topics by showing how even a portal fantasy world isn’t immune to the corruption of real-world problems. Within this realm where teethy ink monsters menace on its readership, Hector and his nonbinary teen, Al, grapple with the lingering influence of stories whose narratives continue to shape their lives long after they’ve been bookended.

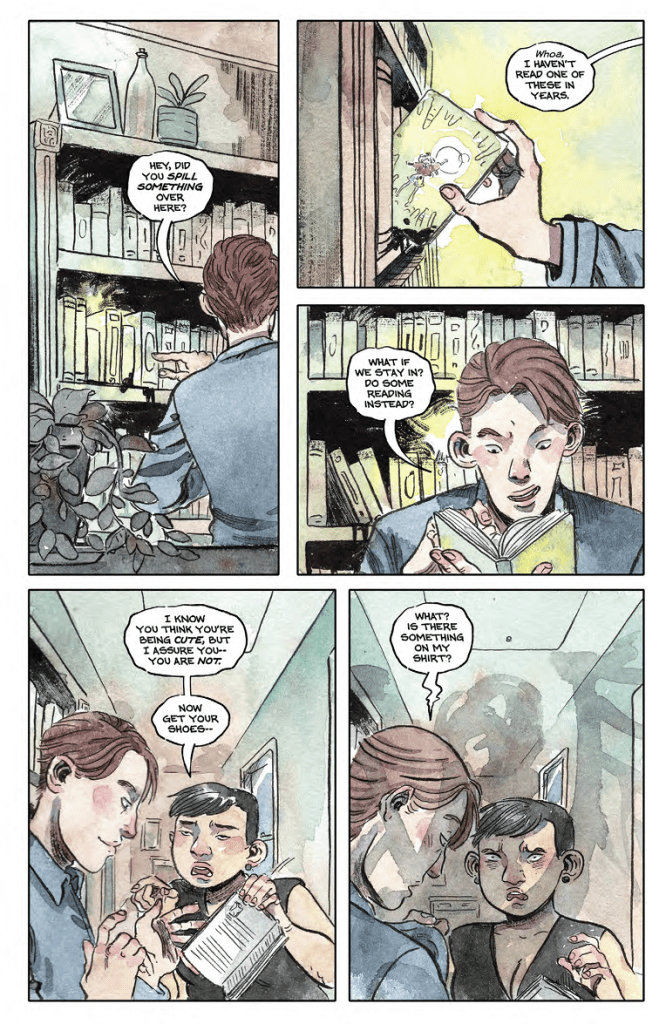

This tension crystallizes around Hector’s co-writer on Vossler’s work, a popular author named Miss Luckwell who is a thinly veiled analogue of a cancelled author in the vein of Rowling. Hector’s offer, while a blank check out of poverty, is uncomfortably fraught for Al. Not only does Hector agreeing to work with Luckwell feel like it’s an endorsement of the Rowling-esque character’s invalidation of Al’s queer existence, as Al wastes no time to point out, but Al is named after Alethea, the protagonist of Vossler’s series that Hector is charged with rebooting.

“Hector is a character who named his kid after a [character] from a novel, and I'm just so taken by the amount of people I know who have named their kids Game of Thrones characters or, God forbid, Harry Potter characters now,” Barbiere said (making me grimace at my own flirting with naming my future child after Petrichor from Saga). “I was so fascinated by this mega fan who grows into an adult and [tries] to share with his kid his love for this thing that he names them after, and just the irony that [Al doesn’t] care.”

For Al, the whole arrangement is a personal affront and betrayal by their father, forcing them to confront the painful legacy of a story headfirst by being inside of it and proposing changes to its heroes, who don’t want to surrender control.

“The story explores the idea of what if you’re ready to move on from certain stories, but they’re not done with you yet,” Barbiere said. “I think we’ve got a little blatant in some of the marketing where it’ll be like ‘some stories will kill’ and very intense things like that, but it really does come from that generational anxiety I feel where we can’t trust people who’ve written works that affect us, and what that means for the future of storytelling.”

Much of the comic’s central tension is embedded in its title—a deliberate double entendre that Barbiere sees as both ironic and provocative. On one hand, it nods to the notion of “the death of the author,” questioning whether a work truly belongs to its creator once it’s released into the world. On the other hand, it interrogates the idea of artistic immortality itself. Can an author ever wholly vanish from their work, or will their presence linger, haunting its narrative, reception, and legacy long after they’ve passed—inversely allowing the author to live forever, even in infamy? Or perhaps a secret third thing where self and work are redefined by Hector and the characters in The Author Immortal, becoming the authors of their own stories.

No matter what readers take away from The Author Immortal’s title, Barbiere admits it still gives him a chuckle since it reminds him of 30 Rock’s “Rural Juror” gag. He’s also grateful he locked in after a quick SEO search confirmed no one else had claimed it for a comic, so that designer Sasha Head could make a beautiful logo on the cover of their comic, and letterer Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou could give the words that encompass its personality life.

On the subject of art design, Barbiere and Beem spoke highly of one another, with Barbiere calling Beem's art a constant inspiration and Beem, in turn, praising Barbiere’s ability to write flawed, real characters for her to play around with through her titular, dreamlike watercolor art throughout the comic. After reaching out to Beem, remembering her work on Swamp Thing, Barbiere’s idea for The Author Immortal expanded from a straight fantasy to a tale that more confidently explored a character-focused take on its premise. Along the way, Barbiere recalls answering Beem’s creative prayers coming off Sarah Miller’s YA book You Belong Here, to depart from drawing so many hallways and characters in an otherwise great book and “have some fun with monsters or something crazy.”

“Morgan's character acting on the page is phenomenal,” Barbiere said. “Some people struggle when they get into [comic book writing] because if they overly visualize, the art can look wrong to them. I love just being surprised and, without sounding narcissistic, so much of Morgan's acting makes me laugh on the page and makes me smile. She really brings it to life. It's been such a joy and inspiration to me. It really does help me find the characters when we see them, and I see their acting and how Morgan renders them, and just the amount of design she's doing on the page.”

Barbiere notes that many fellow creator-owned authors fall into the trap of hastily jumping into action in the first issue trade, rather than allowing the story to develop and unfold naturally. With The Author Immortal, it was paramount for Barbiere to do justice to establishing its characters and world instead of blitzing toward its anime-esque isekai gimmick.

“There's a version of this book where they get isekai’d on page five and immediately thrust into the fantasy world,” he said. “I wanted to really take our time, set up the characters, but keep it urgent enough that it’s not just like ‘We see 10 years of their lives before we jump in.’”

Thankfully, The Author Immortal’s first issue being 40 pages, Barbiere says, allows him and Beem to give readers time to understand who the characters are without languishing in a setup before its big cliffhanger grabs readers to its story. Should the series catch fire, Barbiere assures prospective readers he and Beem have issue four already wrapped up to keep the story going for as long as folks want to read it.

“I’m very thankful that we have so much that we don’t even really get to in the first five issues that we’re ready to get to in the next arc—a lot of cool world building and history those first five pages flashing back to Vossler hint at,” Barbiere said. “We hope people are excited to find out about it.”

In a market flooded with legacy sequels and algorithm-friendly nostalgia, Barbiere and Beem’s book asks a bigger question: Who do stories truly belong to—the author’s catharsis or the reader’s transformation?

“‘What does it mean to have a story that changes your life?’” Barbiere said. “I think it’s something that people say very casually or talk about in hyperbolic ways, but we want to show characters who that actually happened for, for good and bad, and learn to recontextualize [those stories’ authors] in terms of ‘Am I doing damage with this? Is my obsession with trying to be famous or trying to leave behind work that is going to hopefully live beyond me a good thing or a bad thing? Have I indirectly blessed or cursed someone with it?’ And then, also fictionalizing it: ‘Can this be weaponized through magic? Can this be weaponized through the collective unconscious? What does that look like?’”

“That's the stuff that drives me as a creator and something that very much has been, I think, on everyone's mind. Looking at some of the modern thoughts on Death of the Author, what does it mean that we have work we want to divorce from creators? Do we abandon it? Do we continue it? What can we take from it? It’s different for every single person,” Barbiere said. “Our book does not offer answers to these difficult questions as much as explore them and, hopefully, characterize them, because it’s not gonna be me finger-wagging at you to act one way or another. But I think having that as the spine of our book and this idea of legacy in the dimension of creative work in children, in terms of how you affect the world you leave behind, is really fascinating.”

Barbiere hopes that The Author Immortal will prove to be a work that signals a ripple effect, not just for the reader, but for the industry at large, which decides what stories get told and what stories get buried. As a creator who was burned out doing a lot of books, who was scripting video game narratives and comic book tales as dream projects before it all started to homogenize into a mechanical job where he’d have to pitch new ideas every four months, Barbiere said The Author Immortal was an opportunity for him to take a chance on writing something new that endeavors to tell a tale all his own without regurgitating the echoes from those that came before.

Barbiere compared the experience of writing a metanarrative tale about making art to that of a touring band’s second album, which often reflects the band's experiences on the road and the wildness of their lives. Barbiere hopes The Author Immortal comforts readers afflicted by how they should navigate appreciating or abandoning a work when the faults of their creators overshadow the merit of their creation’s messaging. All the better for it if it catches the eye of lapsed fantasy comic book readers in a sea of big-tent superhero legacy comic series.

“I hope the book succeeds, but I hope it shows that there's more space here, like that's what I love about working at Image and love a lot about smaller publishers who are taking a chance on genres that didn’t necessarily do as well in the direct market. There were years when people said you can't do sci-fi, you can't do westerns, or you can't do romance, but I think we've hopscotched past that,” Barbiere said. “I'm hoping that we can fill that void and live in that literary fantasy corner that a lot of mainstream books don't have, and certainly, don't do monthly anymore. Remind people that there's an audience for that, and, hopefully, capture some lapsed comic readers who maybe came in with Saga or Monstress back when Image was really bringing things out and give people an opportunity to come in on the ground floor.”

The Author Immortal releases in local comic book shops as well as digital platforms on October 1.