The first time I encountered the word “egoist” was while watching the shonen sports anime Blue Lock. By all accounts, it was a solid first foray into how an (ego) death game-lite soccer tournament comprised of nothing but strikers would have hotheads butting heads. However, everything Blue Lock had to offer me might as well have been baby food by the time I finished the underappreciated seinen gem The Climber—a brutal, transcendent tale about when grit and enlightenment arrive a hair too late to save men already ruined by their own compulsions.

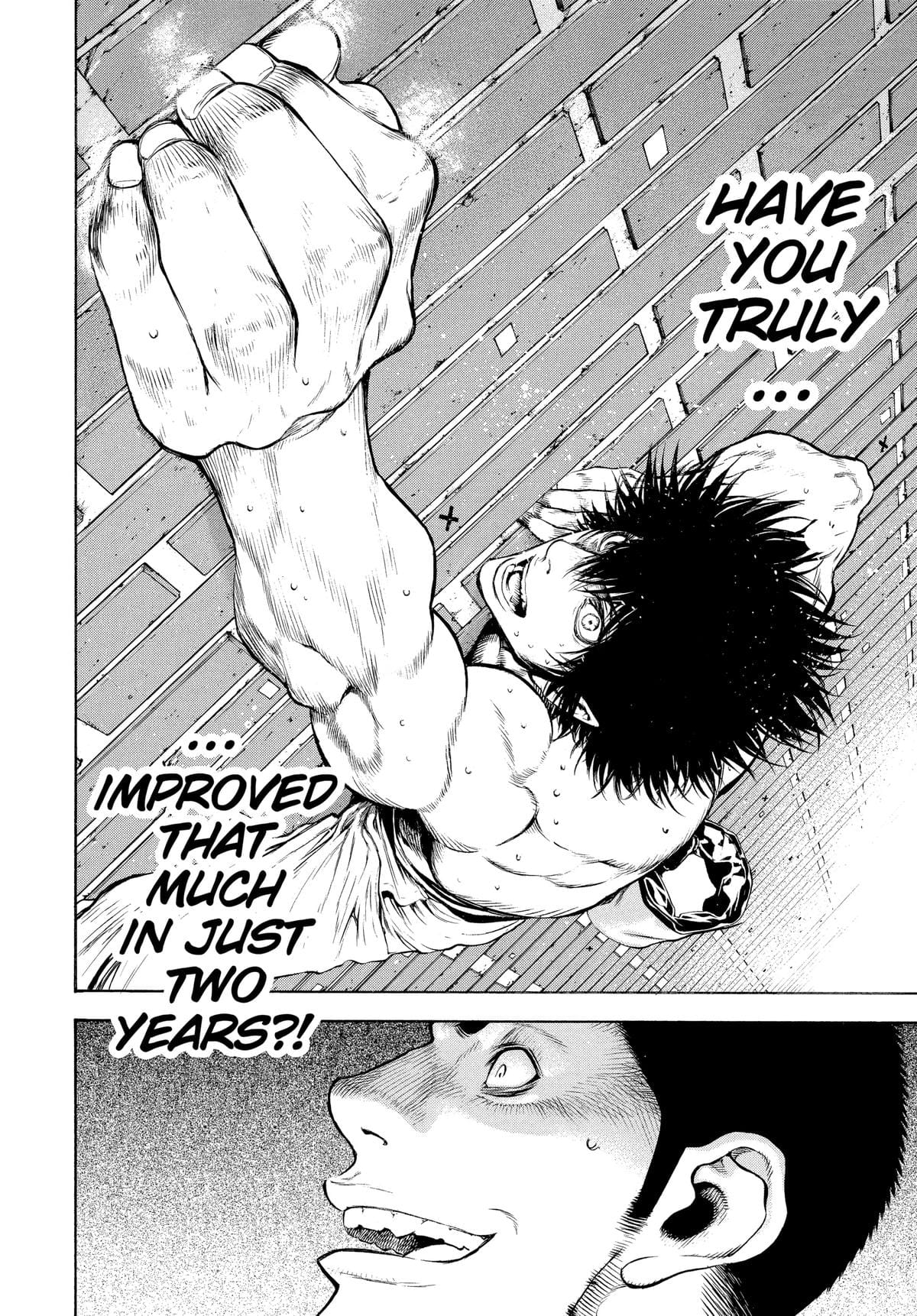

Rather than being a glorified glossary of the sport like its breezier contemporaries, The Climber, written by novelist Jirō Nitta and adapted into a manga by Shin-ichi Sakamoto, is essentially about a group of climbers and the folly and pyrrhic victories of their impulses—namely, those of protagonist Mori Buntarō. When we first meet Mori, who’s loosely based on the real-life legend Katō Buntarō, he’s an edgy transfer student already halfway checked out of humanity. After a run-in with a classmate who impressively scaled the school roof just to poke fun at Mori for being an antisocial prick, Mori repeats the climb, to the horror of everyone at the school, without a belaying rope. The instant he pulls off a ballsy double dyno jump to the school roof, Mori’s life shifts into a new paradigm as he chases an insatiable high for climbing, a sport the manga frames as his supposed salvation.

(Viz Media)

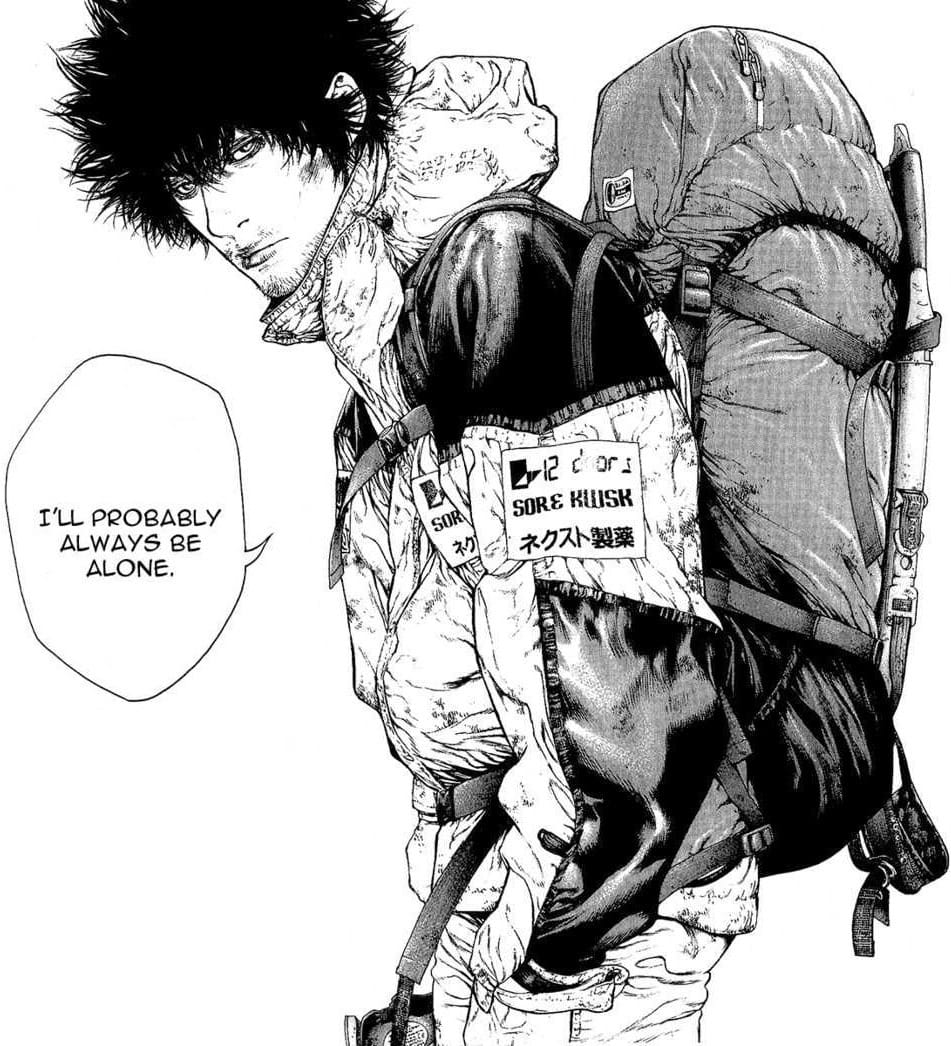

At the onset, Mori’s got everything your typical shonen protagonist would have: a built-in rival in his former bully turned climbing senpai, a mentor in his homeroom teacher and climbing coach, and a cute girl cheering him on from the sidelines. All signs point toward a clean, redemptive path to being a normal guy. But climbing doesn’t save him; it drags him deeper into himself. Mori doesn’t want to tether himself to a partner—he wants to be a solo climber, and if he could help it, he wants to be a solo climber without the lifeline of a belay rope. What follows are chapters, cleverly stylized as “climbs,” that amplify everything fundamentally broken in Mori long before they ever offer a way out—which he frequently refuses—as the manga tracks his psychological descent with grisly patience, from dropping out of high school to the isolating, obsessive adulthood that cements his effigy as the “immortal climber.”

Part of what makes The Climber so arresting is its insistence that the logic of “the ground” does not apply to the logic of the mountain. Down here, cutting a belay rope is unthinkable. Up there, if it comes down to severing that line or dying alongside your partner, you cut the rope. The manga never sensationalizes this binary choice of extremes; it simply presents the reader with the reality of a world where survival demands choices that would make no sense to anyone not already resigned to the possibility of dying for having made the climb in the first place.

(Images: Viz Manga)

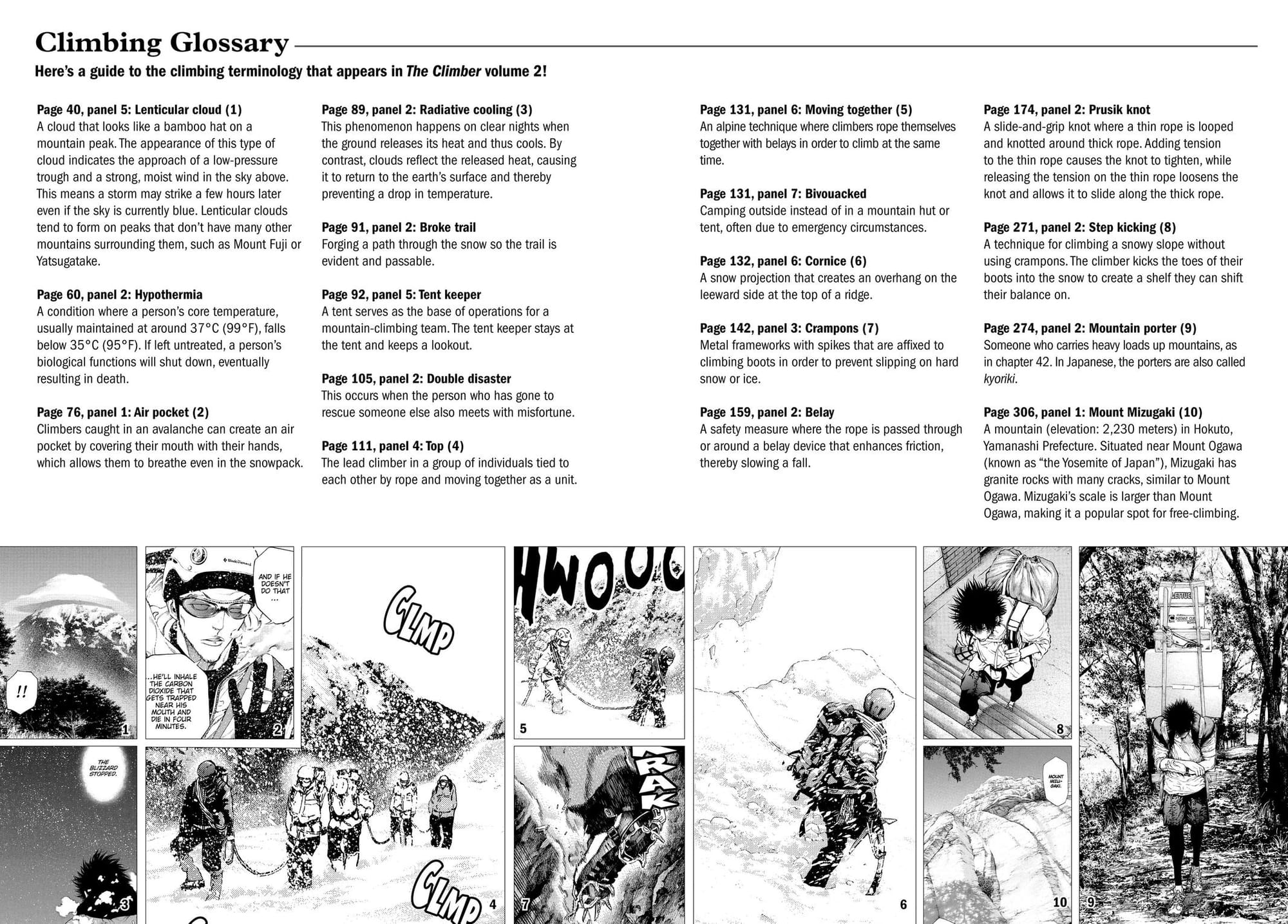

To keep readers grounded without slowing the pace, each volume includes a glossary of climbing terms—clean, unobtrusive, and genuinely helpful—as well as interviews with real climbers explaining why they do what they do. But as the series reminds you, just because you can cut your ear off doesn’t make you Vincent Van Gogh. The Climber interrogates the “Why do you X?” refrain that runs through other art/athletics‑driven stories like Look Back or 100 Meters, only here the characters are often too far gone for a redemption that isn’t self‑destructive. Real egoists, the manga argues, are R.U.N.s: revolting, ugly, nauseating, and shameless—and The Climber is packed with them.

No arc better epitomizes the ambitions and the hubris of an egoist than The Climber putting its characters through the wringer in their attempt to conquer K2, one of the five tallest mountains on Earth, and also the deadliest. Given the mountain has killed one person for every four who reached the summit since the year 2021, totalling to around 96 deaths for every estimated 800 climbers who summited by the year 2023, the odds of The Climber’s egoists being successful are dog water considering its climbing team would climb the bodies of their partners if it meant being the first to conquer its eastern face.

(Images: Viz Media)

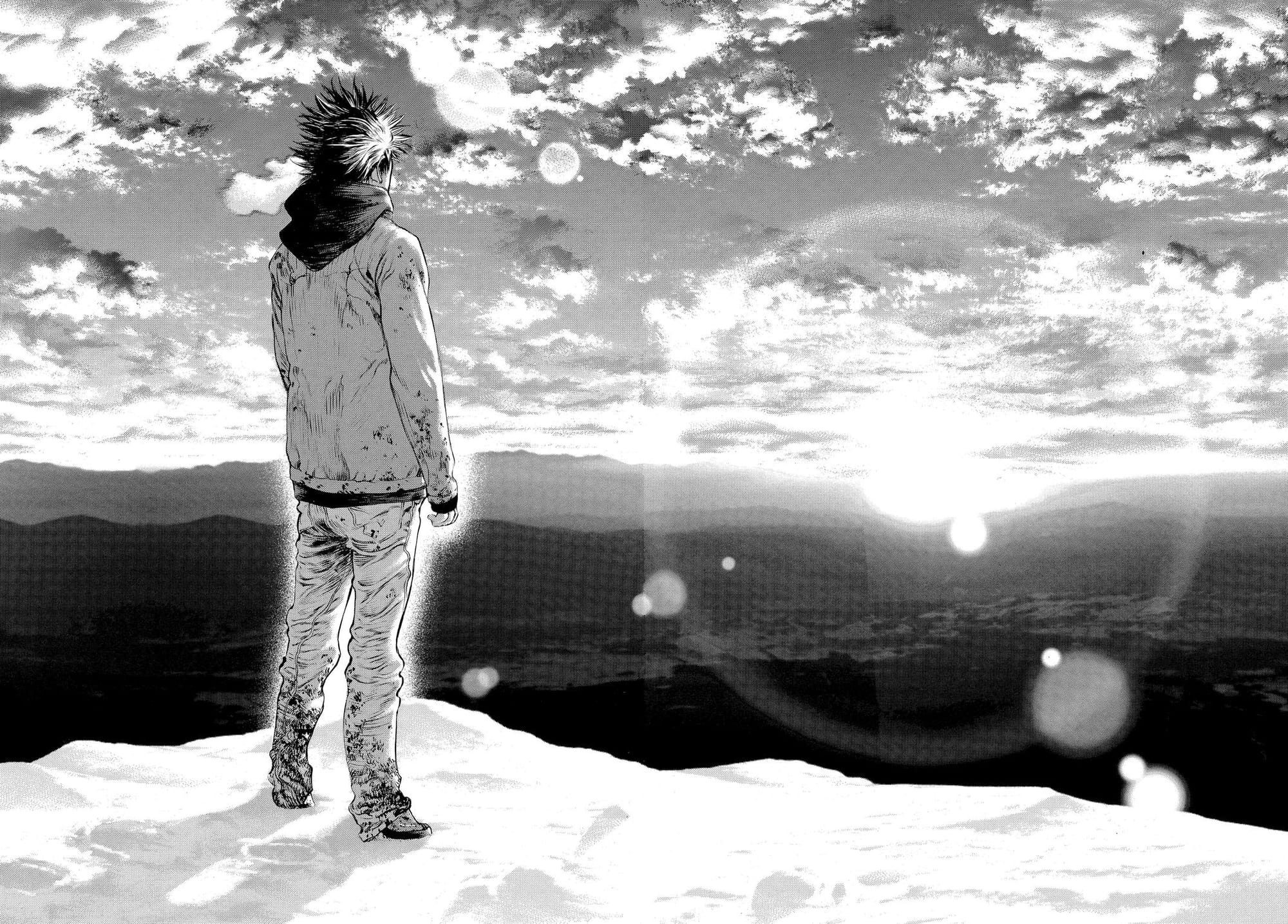

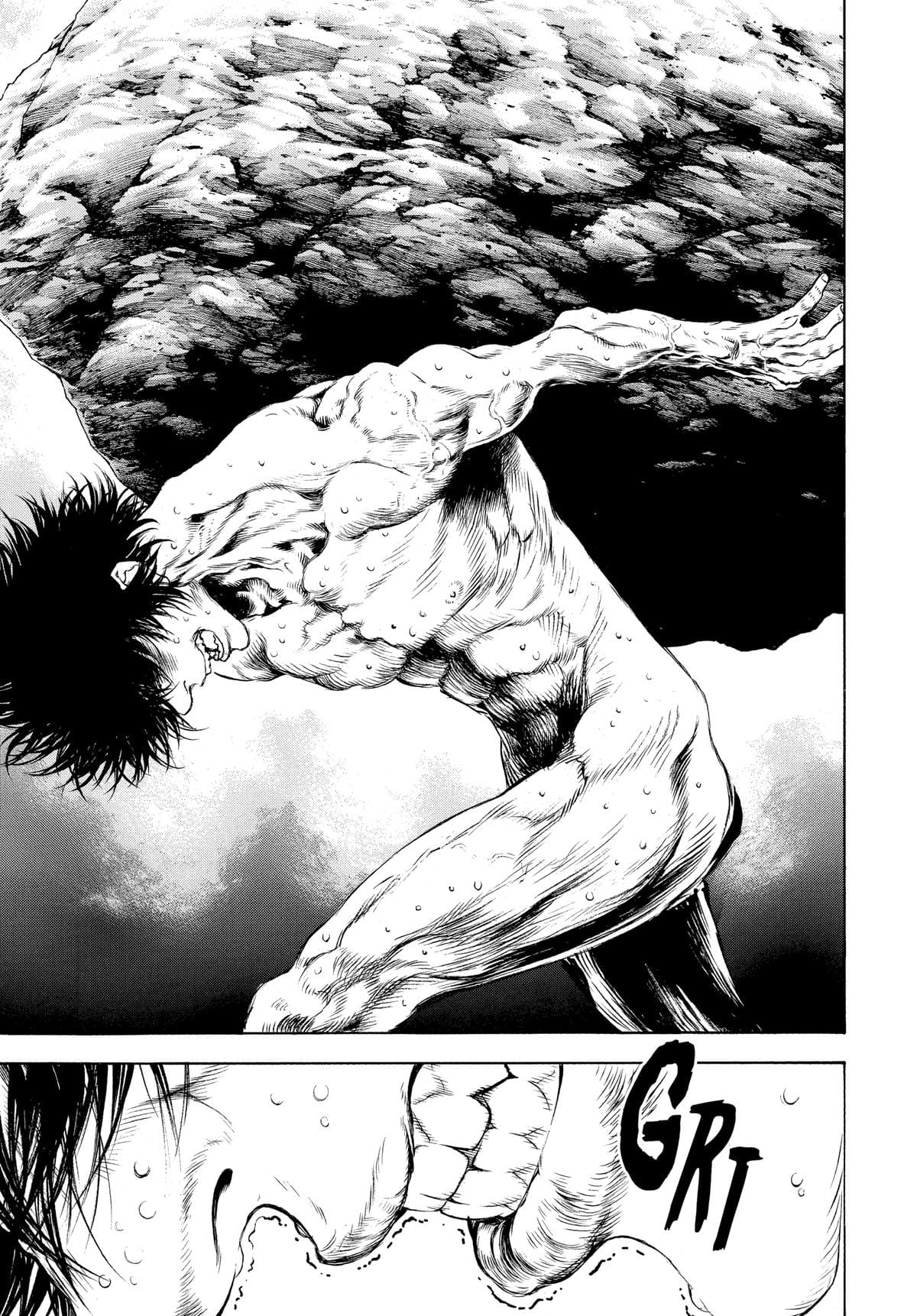

The Climber is also one of those manga where the artistry illustrates its point far more effectively than dialogue ever could. For 170 chapters, The Climber’s pages capture the true devastation of an avalanche, not as the usual cloud of powder sliding politely down a mountain, but as a catastrophic force of nature rendered through panels of skyscrapers and semi‑trucks plummeting downhill at blistering, irrational speeds. It’s a visual language designed to make you feel, in your bones, how dangerous climbing really is. And Sakamoto’s artistry drives that point home, shifting effortlessly between the magical realism of trippy, ethereal, dreamlike climbing sequences and the raw, uninhibited anguish his characters endure as they bivouac on the mountain and as they curl up in a husk below it, should they be fortunate enough to descend a climb by their own power without their frozen carcasses being helicoptered from a rocky metaphor for their own hubris.

The Climber’s answer to “Why do you X?” is a deceptively simple one. Mori doesn’t climb because he loves it, nor does he do it to be the best. He does it because it’s natural to go where you feel compelled to go. And, as in life, the path that demands the most courage is, more often than not, the one you’re supposed to take. Whether that place is the zenith of a man‑killing mountain, or its nadir, where the people who love you white-knuckle it out through deafeningly silent weeks for your safe return. Along his trek, Mori metamorphosizes from an irredeemable little shit into someone worth rooting for one brutal climb at a time.

By the time I tore through The Climber, taking many a “woosa” break, I felt I’d read a masterpiece on par with Vinland Saga. It gave me a new appreciation for climbing—and scared me straight out of ever wanting to solo climb a mountain, much less face life’s less voluntary obstacles alone.