Early in the prologue of 2014’s Dragon Age: Inquisition, your spymistress Leliana sets the tone:

“‘Blessed are the peacekeepers, the champions of the just. Blessed are the righteous, the lights in the shadow. In their blood, the Maker’s will is written.’ Is that what you want from us? Blood? To die so that Your will is done? Is death your only blessing?”

There are many such lines of raw, uncut Catholic agony sprinkled throughout the game—and Leliana, a roguish party member from the first game who returns with style, is an ideal herald for such painful evangels. After all, she represents one of the core themes of Dragon Age: the struggle with one’s faith.

As a fully paid-up recovering Catholic who now worships a Goddess suspiciously Marian in nature, I relate to Dragon Age’s Chantry church, its eponymous Chant of Light, and the moody Caravaggisti tones it’s all sketched in. It truly is I Can’t Believe It’s Not Catholicism, replete with Swordlady Jesus, Absent Daddy Figure, The Apocrypha with Political Implications, and Wildly Off Key Yet Weirdly Moving Music.

But the beauty of the series’ portrayal is that it speaks to faith in the more general sense as well. Faith in a cause, faith in oneself, reaching into the darkness of the future and praying that history doesn’t bite your arm off. You must have faith to believe in any cause, and you must struggle with it, knowing you will never receive a final answer. Dragon Age is a highly theological series that nevertheless understands faith as a pillar of even the most thoroughgoing secularism.

The centrality of this idea to the series makes the ruthless elision of faith in Dragon Age: The Veilguard dissonant in ways that would annoy a devout Chantry sister. That absence is baffling considering the game’s story is almost entirely about would-be gods: Solas/Fen’Harel, Ghilan'nain, and Elgar’nan, the story’s three main villains. Veilguard builds a tower of lore atop the Trespasser DLC’s decade-old revelations about the Evanuris, the Elven pantheon. They were not ‘true’ gods, but ascended mortals who commanded powerful magic—and with it, an empire that Solas sought to topple.

The nature of this revelation is cosmic, to put it mildly. These are the Elven peoples’ gods, whom the Dalish, in particular, are raised to both revere and preserve the memory of. Now, two of them, the aforementioned Elgar’nan and Ghilan'nain, have revealed themselves to Thedas as power-mad panto villains hellbent on blighting the planet and cackling in sexy accents. You’d think this would occasion a crisis of faith somewhere in the same postal code as Leliana’s multi-game struggle with her own faith in the Maker.

Leliana appears to your Grey Warden in Dragon Age: Origins as a woman on a mission from God (i.e., the Maker). The Maker, she says, speaks to her and urged her to join the Warden and their gang of misfits on their quest to save the world. But that wild claim is tested again and again; the guardian spirit of the Temple of Sacred Ashes challenges her directly.

“And you… why do you say the Maker speaks to you, when all that the Maker has left? He spoke only to Andraste. Do you believe yourself Her equal?”

Leliana responds with doubt and struggle, faith’s truest handmaidens. In the end, she avers, “I know what I believe!”

But the truth of the claim is left ambiguous. Who do you believe? Leliana or the spirit?

Dragon Age is good at this sort of thing. Leliana again struggles with her faith after the destruction of that very Temple, several years later, claims the lives of Divine Justinia—think of her as the Chantry’s pope—and countless other believers who were trying to stage a peace conference between the warring Mages and Templars. No wonder she asked if death was the Maker’s only blessing.

And further along in Inquisition you meet a figure out of the game’s mythology: Corypheus, one of the Magisters who—stay with me here—broke into the Fade, that realm of dreams, and assaulted the Golden City that sat at its heart. According to Chantry lore, this indiscretion supposedly precipitated the Maker withdrawing from the world and cursing Thedas with the Blight—an oily corrupting evil that nurtures the zombie-like darkspawn who plague the world. But during Corypheus’ best monologue, he thunders to you about his evil plan and concludes, “Beg that I succeed. For I have seen the Throne of the Gods, and it was empty!”

Proof that there’s no Maker, surely? Well, who do you believe? An evil would-be god who’s high on his own supply? Or your own faith that the Maker has some grander plan here? Or neither, if your Inquisitor’s inclinations lay elsewhere?

The game does not answer this question for you; you can only draw your own conclusions.

After all, you meet Divine Justinia herself in the Fade, later on. Her spirit guides and even saves you. Or… is it really her? Perhaps it’s just some spirit of Curiosity or Virtue that’s filched the late Divine’s memories. When you ask her, she is deeply equivocal, telling you, in essence, that the ‘truth’ of her nature is for you to decide. There are no Answers.

Only more mysteries.

Whom or what do you believe? And how do you wrestle with the doubts and contradictions thrown your way?

Veilguard, rather astonishingly, does none of this.

The game’s best segments involve Solas’ memories—specifically, his regrets. They’re brilliantly written, and make for some solid gameplay that allows your Rook to literally, physically explore the deepest, most forgotten history of the realm that made Thedas everything it is today. It’s bitterly satisfying, often dark, always moving.

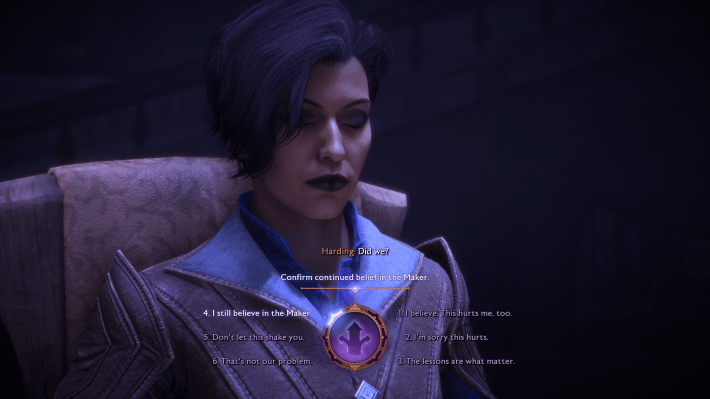

In response to one memory, your party gathers to discuss the theological implications of what they’ve witnessed. Emmerich remarks that, if true, this memory of Solas’ might disprove the entire Chant of Light. And Rook? Well, they can respond with some variant on “whoa, that’s crazy.” And then it’s never brought up again.

The same is maddeningly true of Bellara, whose response to the gods she was raised to believe in being evil mortals is, at least early on, more bathos than pathos. There is one (1) conversation she has where she expresses anxiety about how Elves might face even more discrimination and abuse from humans because of Elgar’nan and Ghilan’nain’s depredations. Rook is afforded one (1) possible response to this, and then the matter never surfaces again. Not even in Minrathous, where the word “alienage”—the ghettos to which Elves are confined in human cities—is never mentioned.

The truth of the Evanuris is profoundly consequential, theologically and politically. The flame that the Dalish had striven to keep alive for centuries was a wicked lie—to the point of being a cruel joke. Their myths were nothing more than the propaganda of tyrants. Solas’ revelations offer a profound challenge to the Chantry’s teachings. Yet no one seems to struggle with this. Ever.

Dragon Age never made fools of the faithful. There was always somewhere for faith to live, and it was revealed to be the fountainhead of virtue as well as evil. For every zealous, abusive Templar, there was a true Champion of the Just; for every conniving sister, there was someone like Leliana or Seeker Cassandra, for whom faith was an inspiration to do good in the world. And there was something quite beautiful about the fact that your Warden, your Hawke from Dragon Age 2, your Inquisitor, could explore ancient secrets few were privy to, yet only find more mysteries than answers. This is a realistic and respectful reflection of faith—it’s a beautiful, lifelong struggle.

Veilguard, by contrast, is a parade of Final Answers that the game has little interest in exploring. While there are hints of doubt entertained about Solas’ regrets, there is an overriding sense that you are, essentially, looking at objective recordings of history.

This is in stark contrast to something Solas himself said in Inquisition about the Fade—the realm of dreams and spirits where these memories play out in Veilguard. Your Inquisitor can ask him what he’s seen in the Fade, and he gives an example drawn from the series’ own history, such as the Battle of Ostagar, which opened Dragon Age: Origins. Teryn Loghain MacTir left King Maric (and your Warden) to die to a horde of darkspawn by calling an early retreat.

You can excitedly ask Solas what ‘really’ happened. But, he says, there is no Truth to be found. Only the reflection of peoples’ experiences and memories. Thus, some view Loghain as a hero who saved the army from a vainglorious suicide march by a naïve king, and others view him as the traitor who condemned the king and the Grey Wardens to death. There is no truth, only perspective. The elemental stuff of history.

To have faith is to know that silence is sometimes as eloquent as song. The Dragon Age series makes much of the absence of the Maker—the one true god, according to the Chantry. The Chantry, as the name implies, is all about song. Its biblical equivalent, the Chant of Light, is meant to be sung (though, as anyone familiar with the droning non-singing of Catholic liturgy knows, the definition of ‘music’ is quite loose here too). But for all that, it’s still important to wrestle with the Maker’s lack of an answer, as Leliana did in that Inquisition scene.

Dragon Age’s earlier games thematise silence beautifully. When the series presented you with mystery, it enjoined you to embrace the silence and think with it, to embrace the beauty of all you didn’t know and might never know. Veilguard is quite noisy, however. It barrages you with cosmic truths that are inarguable. The answers that seemed to elude believers like Leliana. This would be more manageable if you could wrestle with those answers, but that isn’t forthcoming either.

For all these cosmic revelations in Veilguard, neither of the two Dalish-raised members of your party—Bellara or Davrin—seem interested in engaging with the obvious questions. The Evanuris are simply evil and must be defeated. There are no Andrastians to struggle with their faith in the Maker. The only Chantry in the game—an Imperial Chantry, no less—is mostly a combat zone. There are no Hahrens or Keepers to struggle with Elven faith. We meet exactly one believer in the collectivist Qun, in a game that takes place in Northern Thedas where the endless war between the Qunari and Tevinter is far closer and impactful.

It's not a coincidence, I think, that Veilguard’s best bits are places where the game finds space to portray doubt and struggle, and just a little of that all-too-precious silence. After Solas’ sudden but inevitable betrayal—which necessarily occurs after you unavoidably send one of your companions to their deaths—your Rook is riven with doubt and recrimination. It’s a long dark night of the soul in a Fade prison where you’re tormented by the consequences of your leadership. At last, the flagellant’s whip from Inquisition had returned. And it is here, of course, where you confront a terrible truth: your beloved mentor, Varric, had been dead this entire time. In the Fade prison, Varric himself—or perhaps another spirit wearing his memories?—helps you come to terms with this.

Even if it, by itself, wasn't enough, I still found myself saying: “There, at last, was the mystery I was waiting for!” Yes, it was objectively true that Solas had messed with your Rook’s mind, hiding Varric’s death from you and manipulating your memory of him. But who was this in the Fade?

As in previous games, you’re left asking the most important question Dragon Age ever asks: whom, or what, do you believe?

We learn a lot from such questions. But even this pivotal moment couldn’t redeem the fact that such struggles were too thin on the ground throughout Veilguard; it was a rare point of light amidst a relentless procession of Answers that you can’t even begin to wrestle with.

My recent replaying of Inquisition spoke to my spirit in a way Veilguard didn’t—a spirit battered by the events of a brutal November, a rending of the ideological sky that has me questioning my own future as a trans woman in rather existential terms. Inquisition’s approach to faith soothes the broken heart of a believer who still wants to believe, even when the sky itself is torn apart. It is a balm in the way that a good song is when it gives voice to your exact mood.

What much of Veilguard offers is not uninteresting, but it felt strangely unequal to the current moment, despite all the ingredients being there. The terror of ancient evils continuing to haunt us, the shattering of old certainties, institutions that were never supposed to fall, failures so systemic that the only hope seems to lie with those of us in the cracks. And yet, the lack of any kind of struggle with faith—theological or political—makes it all feel soulless at times.

There was one other notable exception, and it’s worth closing with.

Neve Gallus, Veilguard’s enchanting noir detective, had a storyline that ended up making me cry precisely because of how much ground it managed to make up in the faith department, despite it being a thoroughly secular story.

She’s on the hunt for an old foe, a cultist who is tormenting the residents of the Dock Town slum in Minrathous. The cultist had slipped through her fingers before, in part due to the city’s enduring corruption. She has a crisis of faith. What good are her efforts to save the day and help Dock Town when people like that damned cult leader can just keep coming back and hurting people without ever experiencing a single consequence?

“Sometimes it feels as though the city itself stabs me in the back,” Neve says with painful relatability.

I lost it then. That was the first time Veilguard broke me. It was the cry I needed, when this cruellest of Novembers came stealing hope away. The second time I broke was in the Fade, faced with Varric’s mystery.

The point of these struggles with faith is not to find an Answer. It is to cry and find a reason—your very own reason—to keep going.