As far as I can tell, the Moby Dick marathon is a thing simply for being a thing. There are a surprising number of gatherings dedicated to getting through Herman Melville’s dense 1851 whaling classic in one uninterrupted go. You’re probably familiar with the outline of the book–“Call me Ishmael,” Ahab, the white whale–but might not know that the plot is actually the minority of its roughly 600 pages and 135 chapters, plus epilogue. If you know about the rest of it, you’re probably asking what my friends asked me when I told them I was going to a two-day Moby Dick marathon in Mystic, Connecticut: why?

My “why” is because I’m a sucker for anything that requires endurance. It’s because I used to go to the Mystic Seaport Museum as a kid and couldn’t pass up the chance to spend a night in its recreated historic village. It’s because Mystic’s marathon takes place on a tall ship called the Charles W. Morgan, America’s oldest still-floating commercial vessel and the last survivor of a 19th century American whaling fleet. I also went because, for much the same reasons Ishmael says he goes to sea in the book’s opening lines–"whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet"--the marathon sounded like the opposite of the way I spend most of my days camped out in front of my computer, pinned between the despairing onslaught of the news and the relentless pressure of running a business. I wanted to be with strangers I didn’t know from online, with a paper book before me; I wanted ropes and wood and water; I wanted to do something weird and silly and most likely miserable that was about as far from my daily life as I could get.

The 2025 marathon, which ran from July 31st to August 1st, was the Seaport’s 40th, making it the longest-running such event, though not as well-known as the most famous iteration in New Bedford. I imagined huge crowds, a ton of pomp and circumstance, an abundance of rules to keep attendees from wandering off into the museum grounds at night or falling into the river. I kept worrying at the Seaport’s ticket page in the week before, wondering if I should buy general entry in advance in case the museum’s sizable grounds sold out. But instead it was a small group, numbering less than 30 overnight with more during the day. Besides asking us to not eat onboard the Morgan, Seaport staff seemed to trust that anyone who showed up could take care of themselves and their temporary home. One regular participant said she felt like the Seaport doesn’t even really advertise the event; I’m not sure if that’s to keep it small since there’s only so much room, though the overnight reservations were capped at 100, or just how the Seaport operates.

After the event, organizer and Melville scholar Mary K. Bercaw Edwards told me that when things started in 1986, they basically decided to do it in honor of Melville’s birthday and because Mystic had a whaling ship, eventually whittling the event down from a week (they were done with the book after three days, she said) to 25 hours. Organizer Jan Larson, inspired by Ulysses marathons, told The Washington Post in 1991 that she’d initially had trouble selling the event to the museum’s board: “a Moby Dick reading is not exactly something that's going to pull Mom and Pop and the kids off I-95. They thought it might actually turn people away."

I spent a few years in my 20s living on a WW2 rescue boat turned ferry turned home for various queer punks and art weirdos. During the marathon I told several Seaport employees about the summer I called the Seaport’s shipyard for help when our boat sprung a leak, recreating the consternation on the other end of the line as I explained that no, I wasn’t in Mystic and no, the boat had no hope of getting there, ultimately admitting that I just needed to talk to anyone who wouldn’t hang up when I told them my boat was old and made of wood.

The employees I told this story to reacted with the same polite bafflement as those folks at the shipyard did back then, but it at least let me start a conversation with them about their own “why”s: what brought them to the Seaport, why they could recite maritime history or had strong opinions on sea shanties or knew how to row a whaleboat. Niche interests or careers in museums had brought them there, or they’d grown up going there like I had, or they just knew boats. Through the event, I admired the way employees were on hand to keep things running but also seemed happy to be part of it, maintaining the boundary between worker and attendee with professionalism without making me feel like it was my fault they were stuck so late at work, something I felt worried about because I’m me. At one point an employee showed us a spot where we could come and go from the event after hours, and they seemed unruffled when I joked that they shouldn’t give me the knowledge to basically sneak into one of my favorite childhood haunts at will.

I was stunned by how many people at the marathon read to me as trans or queer. A trans guy friend attended the beginning with me, and we kept nudging each other to point out this or that person while hoping we didn’t seem like we were gawking. We wondered if they could tell we were trans too, joking that while two short bearded bald guys seemed like an unmissable indicator, especially when we opened our mouths to read from the book, maybe that doesn’t scream “trans” to younger people these days, when you don’t often see trans guys as deep into their transitions as us in media. At one point I awkwardly pressed myself into conversation with someone and, when they brought up their transition, eagerly revealed “I’m trans too,” only for them to nod and keep talking as if I’d interrupted to tell them the sky is blue. When I asked them “why are there so many trans people here?” in my most high-gossip tone, they just said that Moby Dick is a pretty gay book.

I was desperate to talk to anyone who looked the least bit trans or queer, but I felt like they weren’t as surprised to see me here the way I was surprised to see them. Over the course of the marathon I reflected on how maybe, for my friend and me, seeing so many trans people out in the everyday world is still a marvel and a rarity, where for folks decades younger, it might just be normal. Growing up in Connecticut, I didn’t know any queer people outside of the nascent internet; I was bullied by my peers and left to that bullying by teachers. (After I graduated high school, many of them wrote me to acknowledge my experience and explain how they could have been fired for their own identities, something I’m only slightly more sympathetic to today.) When I worked at a camp in my hometown the summer before I started testosterone, one little kid who clearly had gender stuff of their own once, when kids started arguing about whether I was a boy or a girl, solved the argument by brilliantly announcing “Duh, she’s a boy!” Through that summer I went out of my way to praise them to their mom, all while ignoring other parents who would look at me with disdain or call me “it” when they thought I couldn’t hear. Seeing so many trans people at the Seaport, I wondered what it would have been like to see them there when I was little, what would have told me there was a place for me in the world the way I hoped I had for that kid at camp.

It felt movingly full circle to spend time in a place that figured so big into my childhood with people who shared my identity, and it gave the event a communal feel that would come to sustain me from noon on Thursday to 1pm on Friday, when I hunkered down with all these folks to carry Melville’s entire wandering book from its start to its finish. When I’d forget my way around the museum in the dark, or couldn’t find a spot to get out of the rain, or when I’d get lost in a journeying sentence and needed someone to tell me where we were, it was beautiful to look up and have another trans person to guide me.

The marathon began with a shockingly tall actor, later performing a play about Melville, reading the famed opening chapter on the deck of the Morgan. Attendees arranged ourselves wherever we could, from sheltered benches to the floor to against the masts. A sign-up sheet went around to pick a chapter to read yourself, and a large board with a magnet kept track of what chapter the group was on. Our read-aloud skills ran the gamut. I rushed and mumbled my way through Chapter 15, where Ishmael and Queequeg eat at the Try Pots. My friend, a kids’ book author and ex-librarian, loudly and legibly dispatched Chapter 18, where the pair sign up aboard the Pequod. One woman who read was utterly inaudible and had unfortunately picked a long chapter, which at least let us bond with some of our fellow attendees as we struggled politely to follow along. Someone who would read many times over the night did brilliant voices for inn-keeper Mrs. Hussey and paused to go “yikes” at one of the book’s many troubling, dated lines. I overheard some people jockeying and bargaining for their favorite chapters, while others, like me, just grabbed whatever was available.

Since it was still museum hours, my friend and I took breaks to explore the Seaport. We missed a good chunk of the early reading, though I told myself it was OK because I’d read maybe a third of the book before. I ducked into one of the food shops minutes before it closed to cram down a sandwich; attendees were encouraged to bring their own food but had to keep it in their cars until the museum closed, and since I’d taken the train I’d come armed only with nuts and beef jerky in plastic bags.

Back on the Morgan, we alternated between reading along, listening, and getting to know the people around us. We fell in with two folks whom I later learned had just met that day by sitting next to each other; one of them was here for the fourth time and had stayed overnight twice in the past, though was spending the night in her bed in Mystic for this one. She and her husband, I learned later, had both been editors at a prominent running magazine (she told me I “looked like a marathoner” when I turned the subject to running, a thrilling compliment) who’d retired to the town. Along with some friends she’d adapted short versions of classic books, including Moby Dick, a copy of which she presented to the organizers at the end. During a break for people to get things from their cars, she told me, with what I read as the love of suffering of a distance runner, that there had never been breaks in the past. But I could understand the desire for it; it felt rude to wander in and out while people were reading, but it was also hard to sit quietly for that long, reading Melville’s winding prose, and the hard deck of the Morgan and the muggy weather didn’t make it much easier.

After my friend went home, with no excuse to leave the ship, I started to feel the gravity of the hours before me. I worried that my attention was too burned from the frenzy of social media to actually sit through the book; I call myself a reader but I struggle with books these days, and even sometimes have to watch something on my computer in the background to keep myself engaged. I put my phone on airplane mode, as much to keep myself from checking my email as to preserve its battery. I chastised myself when my mind wandered, though I also reminded myself that surely no one was going to spend the next 25 hours doing nothing but reading every word.

Here’s where the challenge of Moby Dick comes in: The actual plot is probably the thing the book spends the least pages on, with the majority of it taken up by basically whatever came into Melville’s head. When we got to the first of these parts, Chapter 32’s “Cetology” and its scientific efforts to catalogue different whales, a groaning cheer went up for the person who’d chosen to read. Defector worries these chapters are “filler” and “pretentious,” though also writes that “what Melville achieves, what many of the best books achieve, is a consuming rhythm, an internal logic that makes it so almost any digression feels motivated, interesting, even important. Here is a novel that follows men trapped within the groove of a destructive and dying industry, one whose violence and cruelty is held up as one of the few remaining paths to glory.” The book is full of random-feeling plays and songs; there are long explanations of whales and parts of boats; there are stories about the Pequod’s crew or from passing ships that meander and circle and obscurely reference until if someone offered me a million dollars to say what was going on in them, I don’t think I could. Back in the spring I’d gone to an opera of Moby Dick, and during the reading I was glad I had; when I’d start to despair that we were lost on an ocean of meaninglessness, I could remind myself that no, really, there’s a novel in here somewhere.

It was, frankly, frequently boring. But that’s what I’d wanted; beyond the absurdity of the adventure of a book-reading marathon on a boat, I wanted to disconnect from all the noise in my head, wanted to see if I could just be here and do this, to look at what was in front of me. It felt not dissimilar to a whaling voyage; as Melville writes,

In this tropic whaling life, a sublime uneventfulness invests you; you hear no news; read no gazettes; extras with startling accounts of common-places never delude you into unnecessary excitements; you hear of no domestic afflictions; bankrupt securities; fall of stocks; are never troubled with the thought of what you shall have for dinner–for all your meals for three years and more are snugly stowed in casks, and your bill of fare is immutable.

The museum closed at six, and with just marathon overnighters left, I realized I was in it now. I chatted with a Seaport employee I’d previously seen performing sea shanties, a lifelong passion of theirs. When I asked them if 2021’s sea shanty boom had been good for their career, they told me that actually the biggest effect they’d seen was from the soundtrack to Assassin’s Creed games, from which kids visiting the museum regularly make surprisingly obscure requests.

Night fell. Employees built little pockets of light from LED ship lanterns and lit a path to the bathroom building across the museum grounds. The cloudy skies turned to drizzles of cold rain, and I rued my last-minute choice to swap out my warm hoodie for a lighter one. I wrapped myself in my raincoat and the camping quilt I’d brought along, worried about the rest of the night if I was already chilly and damp. Meanwhile, the reading went on and on, people holding flashlights for each other and lighting up their books with their phones. I regretted not swapping out the batteries on the pocket flashlight I’d grabbed off the shelves of the hardware store before leaving town. As Ahab introduced his quest against Moby Dick in Chapter 36–“I’d strike the sun if it insulted me”--a hard wind rocked the Morgan in a moment that felt scripted.

But dramatic punctuations were few and far between–basically, it was just a little group of people reading an often-boring book in a growing rain. I started, legitimately, to panic. A flipside of the rut that drove me to the reading is that I’m pretty settled in my solitary ways, and I suddenly wondered if spending all night with strangers in what was basically some folks’ workplace wasn’t as up my alley as I’d thought. I became aware of the darker side of what had been my light-hearted quip about how I was basically stuck in the Seaport until 5pm the next day: There was nothing to be done if I got too hungry or too cold or needed a smoke or just didn’t want to be there anymore. I silently railed at Melville for writing such a long, boring book; I cursed all the weather apps for giving me conflicting forecasts. I didn’t even know any of these people, and for a moment, even surrounded by other queer and trans folks, I felt stupidly alone.

I turned my internet back on to look up late night trains (none) or hotels (too expensive). I took an unnecessarily long walk to the bathroom. On the return I stood for a while looking down the deserted street of historic buildings that lined the water, trying to encourage myself with the fantasy of telling my childhood self they got to sleep here before remembering that I wouldn’t even be sleeping. I ducked into the shadows to take a couple surreptitious pulls on my vape, hating myself for breaking the rules against smoking on museum grounds but feeling both desperate and pathetic about needing to pull myself together.

The rain started falling colder and more frequent; I anxiously counted the hours of how long it would be until I’d be back in New York in dry clothes. I was disappointed in myself for how quickly my big adventure felt like it had turned into the bad idea that caused my friends to react with horror when I first told them about it.

Around 10:30pm the reading paused for a performance of sea shanties by the employee I’d talked to before. I huddled close under a sheltered part of the Morgan, trying to take advantage of the reprieve in what was starting to feel like some racist dead cis guy's oppressive, self-indulgent book that I’ve never had strong feelings about anyway, trying to convince myself I hadn’t made some horrible mistake. I kept having to remind myself to listen. I prided myself on recognizing some of the songs they sang, accompanied by concertina and bones, and was excited to learn some new versions. I reminded myself again of what I’d come here for, pushing myself to just be in the moment instead of endlessly narrating the ways I felt somehow deficient for whatever task was ahead of me. I reminded myself that what I love about going on big adventures out in the world is the chance to meet other people and learn about their lives, to be in worlds different from my own. That’s happening right now, I growled, forcing my attention back to the music when my brain would start to gallop with some worry.

I was relieved when the organizers announced we were moving the reading inside the Morgan to get out of the weather. I navigated the narrow stairs down to the ship’s blubber room, a long squat compartment in which most everyone would bang their heads on the ceiling beams during the night, even me who was too short to reach them. It was warm down here, and well-lit, and knowing I wouldn’t be too cold or my flashlight wouldn’t die helped me chill out. I staked out a corner among some barrels, shamefully posted about it despite my vow to keep off the internet, and tried to arrange myself away from the rain burbling through the ceiling.

Once everyone was situated, the reading went on. I read Chapter 57, “Of Whales in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood; in Sheet-Iron; in Stone; in Mountains; in Stars” (that’s what kind of book this is!). The chapter calls people "savages" with such frequency that I regretted not reading it through before picking it, though I got some sympathetic sounds when I groaned "good lord, Melville" at yet-another instance. Once my chapter was done, already tired though the clock was just reaching midnight, I settled down on my quilt for the middle watch.

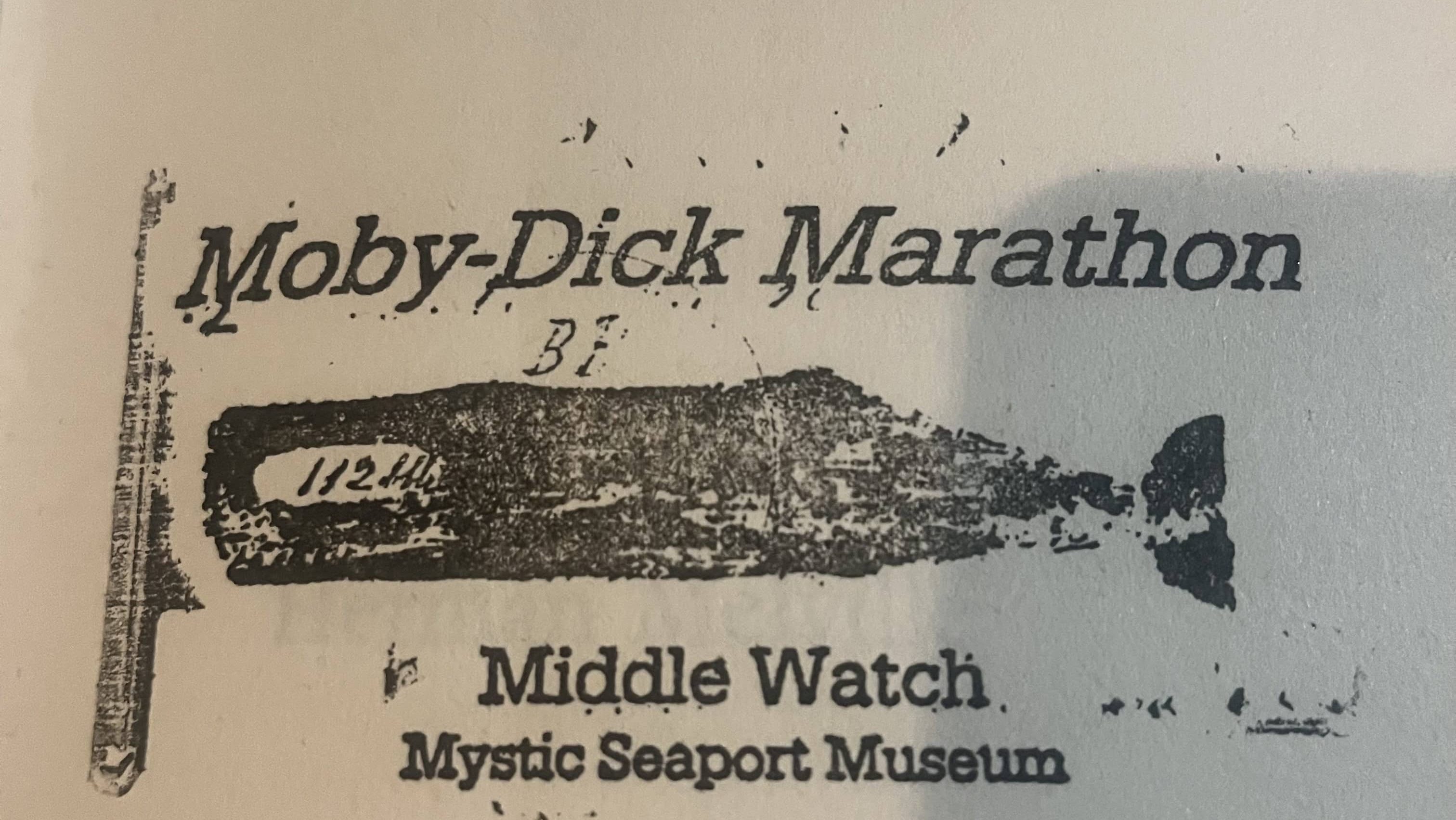

An email about the event details read that “For those who stay through the ‘middle watch’ (midnight to 4:00 a.m.) there will be a special whaling logbook stamp to commemorate the event.” I was curious what a logbook stamp was, and was also not above being bribed with goodies at this point. As an employee later said to me, this is the worst part of the night for a Moby Dick marathon. Beyond the fact that it’s far later than anyone should be awake still reading a dense classic, you’re what the employee called “deep in the book” now, hundreds of pages from the early chapters of meeting memorable characters and setting sail, but still hundreds and hundreds of pages from the Pequod’s crew finally spotting the white whale. There’s nothing before you but an open sea of what more often than not feels like bullshit, digressions into anything and everything and even stories that start with strong hooks wandering off into Melville’s ramblings. I have no doubt all of this is very rewarding to pore over and really come to grips with, but trying to digest it all for the first time when I was already exhausted from my early morning travels was a challenge.

I built my stuff into a little nest among the barrels, using my raincoat as a levee against a growing puddle, and laid down to follow along. Eventually, I decided to nap for a chapter until the applause for a finished reader woke me, read along for a chapter, and then nap for another. These arrhythmic gulps of sleep were less restful than I expected, still believing I could stay up all night like I used to before I hit my 40s. I had to keep contorting myself into a narrowing strip of dry floor as the rain found new gaps in the ceiling. Meanwhile, Moby Dick just kept going, the pace of different people reading aloud far slower than my own reading speed and making me feel like we’d be trapped in it forever.

But through the course of the middle watch my experience changed. I’d later talk to attendees who also admitted they weren’t really able to read the book during the marathon and planned to read it again at home, but I eventually gave up on the idea of being studious and just let the night unfold. There became something lovely about waking up from a doze to find the book still going on without me, a handful of the most intrepid late-night readers calling out their chapters from wherever they were in the room, occasionally buoyed by staff taking a turn. I’d lift my open book from my stomach and slowly but inevitably figure out where we were from some unique phrase, then read along until the book would tip toward my face. I’d surface from sleep into someone murmuring about whales’ eyes or tails or spouts, into Pip falling overboard, into the endlessness of the Pequod’s crew processing blubber and meat and oil and spermaceti, into Ahab getting a new leg made for reasons I missed. Melville writes that “we account the whale immortal in his species, however perishable in his individuality,” and that’s how Moby Dick came to feel, knocking out chapters without even making a dent in the book. But it didn’t feel bad the way it did in my panic up on deck. It felt comforting, like I didn’t have to worry I’d miss anything or let anyone down. It felt like we were moving the book forward as a group, strangers carrying the moment for each other so we could all see it through together. It’s not a feeling I have often in my life these days, and it felt magical to find it in such weird circumstances, though I’m sure sleep deprivation gave it some of its weight.

At 4am an employee announced we’d made it through the middle watch, to tired claps and cheers. They invited us to come get our stamp, and I tiptoed through sprawled bodies to find them. They pressed a little inked image of a whale adorned with the words “middle watch” onto the title page of my book. As I navigated back to my spot, the next reader began.

Around 5:30am I climbed above deck to find the sun starting to haze through the clouds. Despite the fact that water coming down on me inside had made any more sleep impossible, the air was hard and rainless, like the Morgan was making its own weather. I took a little walk through the crunching puddles of the shell-covered wharf, marvelling again at how it felt to be near the big ship at such an unusual hour. Below deck, the reading soldiered on, and I signed up to read another chapter. Around 7 I heard people sweeping the deck and preparing the Morgan for its regular day at the museum; at 8 we took a break for people to stow their stuff back in their cars and to move the rest of the reading to the Seaport’s meeting house so the ship could have visitors. Employees brought some coffee, a welcome alternative to my plan to make cold instant in my water bottle.

Before the reading started again we had the opportunity to take whaleboats out on the water. I tend to think I’m too cool for such novelties or worry that I’m inconveniencing the people providing them, but I told myself to get over it because this was too special a chance to pass up. The sea-grizzled older man organizing things asked if anyone knew how to row, and when no one else in my group raised their hands I admitted I’d rowed some crew in college. I regretted this (I was, in the words of my coach, a “team builder,” though a shit rower) when the man put me in a key position at the front of the boat and told everyone to watch how I handled its nearly 20-foot wooden oar. But it came back to me quickly, and I did my best to follow our captain’s instructions and lead everyone in a row past the front of the Morgan into the river, where he proudly told us few people get to see the boat from this angle. He told us facts about whaleboats and how to handle them, then instructed us on how to turn around and row back. I peppered him with questions as we went–how did he know all of this, where had the Morgan sailed, what was it like to sail with it, why didn’t it sail anymore–that he politely but briskly answered. As it was surely intended to, the small boat against the size of the Morgan drove home the picture Melville paints, how frightening and flimsy whaling must have felt, with nothing but wood and metal and ropes between whalers, their quarry, and the sea.

Inside the meeting house, with people who hadn’t spent the night bringing new energy to the reading, the book moved along through the morning. I read Chapter 117, “The Whale Watch,” where Ahab is given prophecies about his death in such a casual way that I didn’t even realize that’s what they were until they came up again in later chapters. The back parts of the book finally return to having a plot, with the bulk of what most people know of Moby Dick–chasing the whale, the Pequod sinking, Ishmael becoming the lone survivor–happening in the last 50 or so pages. The writing becomes more focused and easier to follow, and everything rushes–as much as Melville can rush, anyway–to its conclusion.

The Pequod meets the Rachel, another whaling ship whose captain is searching for a missing crew that includes his own son; Ahab cruelly rejects the Rachel’s plea for help because its crew has seen Moby Dick. In Chapter 132, the person reading aloud cried as he recited Ahab’s speech realizing the consequences of his lifelong pursuit of the white whale:

Forty years of continual whaling! forty years of privation, and peril, and storm-time! forty years on the pitiless sea! for forty years has Ahab forsaken the peaceful land, for forty years to make war on the horrors of the deep! Aye and yes, Starbuck, out of those forty years I have not spent three ashore. When I think of this life I have led; the desolation of solitude it has been; the masoned, walled-town of a captain’s exclusiveness, which admits but small entrance to any sympathy from the green country without…

Ahab and Starbuck have a conversation I remembered from the opera, in which Ahab movingly tells Starbuck “lower not when I do; when branded Ahab gives chase to Moby Dick. That hazard shall not be thine. No, no! not with the faraway home I see in that eye!” Starbuck tries to convince Ahab to give up the chase and turn toward home, where they can both see their wives and children again. It’s a beautiful, tugging moment, especially when you know what’s coming. Reflecting on the sea weather, Starbuck nudges, “I think, sir, they have some such mild blue days, even as this, in Nantucket,” to which Ahab replies

They have, they have. I have seen them–some summer days in the morning. About this time–yes, it is [my son’s] noon nap now–the boy vivaciously wakes; sits up in bed; and his mother tells him of me, of cannibal old me; how I am abroad upon the deep, but will yet come back to dance him again.

But just as soon as Ahab seems convinced, he falls back into feeling fated to hunt the whale, asking “Is Ahab, Ahab?” to a Starbuck who has already walked away in disgust or despair. Shortly after, the crew finally spots Moby Dick.

They chase the whale over three days. (“Ah! how they still strove through that infinite blueness to seek out the thing that might destroy them,” Melville writes.) Whaleboats are wrecked in the clash (“the odorous cedar chips of the wrecks danced round and round, like the grated nutmeg in a swiftly stirred bowl of punch”) and eventually the Pequod is irreparably damaged. In the final fight, Ahab is tangled in the ropes and is dragged off by Moby Dick, shouting his famous lines

Toward thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool! and since neither can be mine, let me then tow to pieces, while still chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale! Thus, I give up the spear!

The Pequod goes down beneath the waves, and the final line of the story chillingly reads that, after all the great drama of the Pequod’s journey and for all we’ve learned about its crew, “the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.” Together, all of us read the last line of Ishmael’s rescue, floating on a coffin in the abandoned sea, from the epilogue: ”It was the devious-cruising ‘Rachel,’ that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan.” The meeting house erupted in cheers and a standing ovation. The way the book swings back to plot felt incongruous with the cerebral, meandering journey we’d been on since yesterday, but the rush of emotion felt earned. Ahab might not have defeated Moby Dick, but we’d defeated the book.

We took a celebratory group picture, and museum staff brought out a sheet cake for Melville’s birthday. Most people swiftly went home to go to sleep, but I was stuck at the Seaport for a few more hours before my train. I ate multiple pieces of cake, hoping the sugar would keep me awake. I asked museum staff more pestering questions that they answered before tactfully excusing themselves to go about their work days. I explored some exhibits I hadn’t visited yet before finally leaving the Seaport for good. In downtown Mystic, I wandered among crowds of vacationing tourists worried I was terrifying them with my dirty clothes and sleepless eyes, realized I was haunting creepily behind them at restaurant menus when I found myself too tired to navigate deciding whether to go inside for my first real food since the afternoon before. I’m not above admitting I had to hold back exhausted sobs when I found out my train was delayed, then running slowly, and it took hours longer than it should have to get back to my apartment in New York.

But after getting home and forcing myself to shower and (finally!) brush my teeth before crashing, I woke up Saturday morning to find myself drifting back to my copy of Moby Dick, now bristling with specially-made bookmarks and placards commemorating the event. Despite how long I’d just spent with the book, despite how much it had tormented and confused me, I didn’t feel done with it. I still wanted to be in its world, to read what I’d missed and understand what it is about Moby Dick that makes so many people decide to throw marathons for it. I opened it up to those familiar first pages, already knowing both the tortures and pleasures that awaited me, ready to take it all on again.