Black Myth: Wukong does not, ultimately, care what I think about it. To the degree that criticism matters (reporting being a different beast), mine has never mattered less. There is something liberating and refreshing about that. The Journey To The West themed game is a breakout hit, selling 18 million copies in 2 weeks, primarily in China but not insignificantly internationally. It is a very good game – bold, ambitious, and constantly innovative. It is also a little lopsided at times, charming in some ways and less so in others, both of which speak to the relative newness of developer Game Science in producing this kind of game. It is a game that matters quite a bit to the future of games; its ambition should not be ignored.

You can learn a lot about a country by looking at what movies gross the highest there. Many times you will find several American movies on the list due to our outsized cultural presence, but in the case of China it will be movies like Wolf Warrior 2, Detective Chinatown 3, The Battle at Lake Changjin – a mix of comedies and military flicks that you don’t usually watch in the States. Have you ever heard of the movie YOLO? It grossed $479.5 million dollars and came out this year. Though there have been attempts at breakout crossover hits from China (Zhang Yimou succeeded brilliantly with Hero, only to direct the laughable The Great Wall later) most are made for domestic audiences. Though Black Myth: Wukong is almost jarringly in this vein, it differs a little in part because of the nature of gaming and the specific quirks of digital distribution.

Though nobody needs to know how many people are playing a single player game, it is impossible to miss a gargantuan $70 million blockbuster single player game just sitting fully wrapped on Steam beating Counter-Strike in concurrents. Through sheer gravity in a digitally distributed marketplace, it attracts attention in a way that movies often struggle to do unless they arrive on a streaming platform. What’s more, there’s a degree to which gamers can just kind of roll with something if the game plays well and the spectacle is grand enough, and largely that is true here.

Black Myth: Wukong’s popularity in the West, to the degree that it can be quantified, reminds me quite a bit of the popularity of Telugu hit RRR in more ways than one. As pure spectacle, the appeal of that film is universal – you do not need to know history and geopolitics to understand why picking up a motorcycle and hitting a guy with it is pretty sick. But RRR is suffused with cultural, nationalistic and religious symbolism that goes beyond the basic literacy of many Western audiences. Most gamers who are not Buddhist probably do not know who Maitreya is and why they are in a video game, in much the same way that most Westerners who watched RRR on Netflix didn’t know who Komaram Bheem is, why there’s an extended sequence about the god Rama near the end, and the religious and political implications of such a scene.

That Black Myth: Wukong does not stop to explain itself adds to the confidence of its execution. Of course you know who Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie are! Everyone knows that. The game presumes you know Erlang Shen, Princess Iron Fan (Rakshasi), The Bull Demon King, and the demonic child Red Boy. Allusions are made to the shapeshifting bone demoness Baigujing. In the abstract you could argue that God of War does a similar trick, but the prior knowledge of the plot of Journey to the West is far more load bearing here. Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty also does something similar, but it is nowhere near to this level of scale, polish, or success, and it is helped in the West by Dynasty Warriors being a long-running franchise. Compounding this is the fact Black Myth: Wukong is not an adaptation but a sequel to Journey to the West. Save for the very beginning, you do not directly play as Sun Wukong but the “Destined One,” an entirely different monkey attempting to take up his mantle. That the Destined One is a taciturn, silent protagonist is a bit disappointing to me given that Sun Wukong’s whole deal is that he’s one of the biggest loudmouthed pricks in fiction, but this is ultimately a game that is attempting to comment on the story instead of telling it directly, which is the correct approach when limited to 6 chapters and 35-50 in-game hours. Many of the most successful movies about Journey to the West take the tack of either limiting the scope out of necessity or being loose with the source material (Stephen Chow has starred in, directed and written many of these), because you just don’t have the time to do it in a non-serialized format.

I would be remiss to talk about this game without touching on the reporting about sexism surrounding developer Game Science, as well as the very strangely worded list of do’s and don’ts sent to streamers by Game Science collaborator Hero Games. I’m not the best person to analyze the potential misogyny of the Chinese gaming scene or game development culture, but trying to draft this game into a Western culture war has always struck me as funny given how tame the actual plot is. Though it does not necessarily reflect on the development of the game, women are well-represented in the story, although much of that happens much later in chapters 3-5. None of the political issues present in the influencer guide are commented upon in the game itself. For all the controversy surrounding the game’s development and release, the actual text of the game is anodyne in the way that most blockbusters have to be, and which is unsurprising given its source material.

Black Myth: Wukong is a work of gargantuan ambition and enthusiasm tempered by growing pains. Part of this has to do with general pacing and level layout. As some of the largely positive reviews have pointed out, the basic layout of the levels are confusingly similar at times, compounded by arbitrary invisible boundaries, and are easy to get turned around in, particularly since the game doesn’t have a map. This improves a bit as you move away from the first chapter and see other zones that are not just a forest, but levels remain labyrinthine. Sometimes this adds to the general mood of the game. The lack of a map makes the secrets you find feel particularly special. As the game progresses, the settings become increasingly imaginative and robust. You begin to anticipate the ways that the stages wind and twist. In a spider cave later on in the game (note: if you are afraid of bugs, this game is not for you), this is combined with a lot of verticality.

The game does not start on its best foot after its bombastic opening. The combat can feel uneven and sluggish until you hit the second chapter to third and everything finally clicks. Much of this has to do with the general rate at which the game drip feeds you your full moveset, and the pace of combat only makes sense if your full suite of abilities can be cycled and cooled down. Both God of War and Lies of P have similar issues with tech tree windup. In fact, I found many comparisons between Wukong and Lies of P, which seem to find their footing and confidence as they progress. When everything does finally snap into place, the game’s combat becomes as tight as a drum.

Both Lies of P and Black Myth: Wukong are innovative and unabashedly “soulslike,” although the latter is only punishingly brutal in parts and does not contain the signature roguelike elements of a Souls game. FromSoft’s influence is unambiguously present, not just in terms of storytelling, combat and tone, but also in terms of general visual language of the monsters and world. “Between Sekrio and God of War” is how I have been pitching what Black Myth: Wukong does. Both Wukong and P are also shockingly good first attempts at action adventure games, from companies that had little to no experience in it, in ways that add to and at times outdo the games they are influenced by.

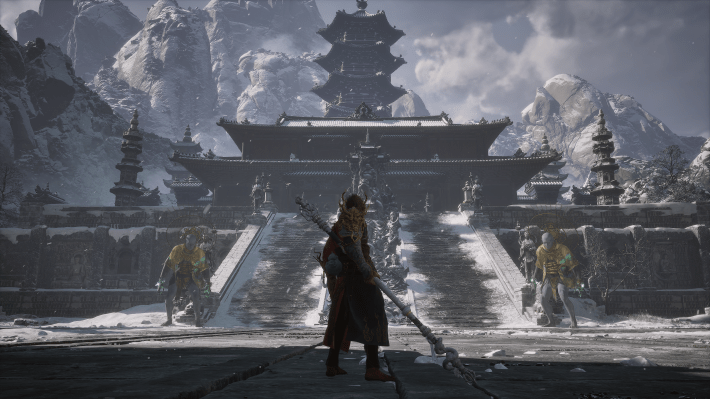

There is a shocking degree of creativity on display in how Game Science has decided to render the universe of Black Myth: Wukong, from towering, trans-dimensional pagodas in snowy climates to dense spider caves. It looks gorgeous, many of Unreal Engine 5’s bells and whistles like Nanite have been turned on, and the game makes extensive use of particle effects in several fights, from billowing smoke to snow and sand or leaves. One fight makes aggressive use of floating pages of Buddhist scripture. Black Myth: Wukong is also a poorly optimized game at times, although definitely not the worst I have seen, with framerates often plummeting suddenly in certain areas. But what strikes me is the sheer confidence, the boldness of every choice in the game.There are no half-measures in Black Myth: Wukong; it is clearly the work of a company that has yet to hit its stride, but which is trying to make a scene with its arrival.

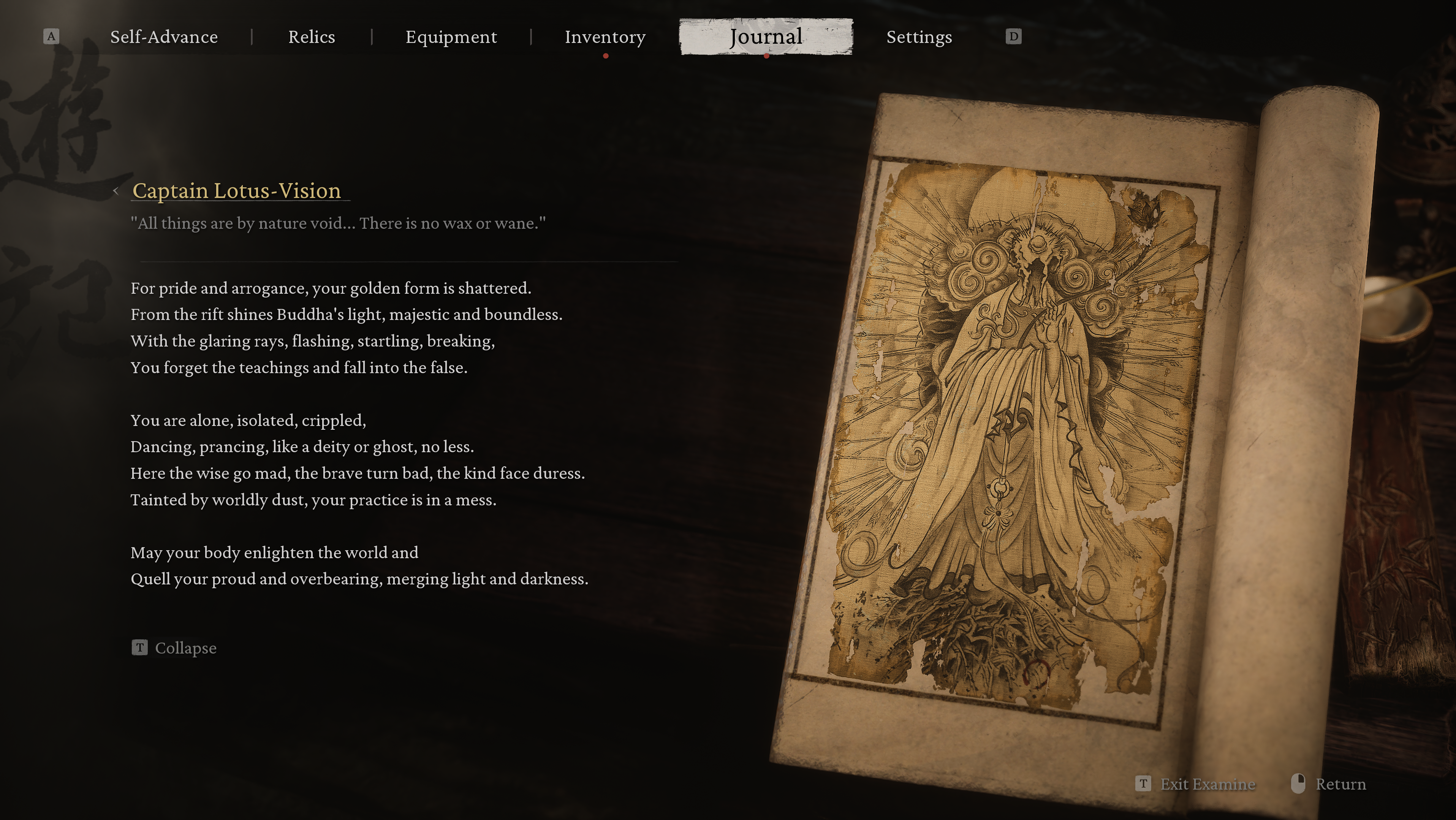

What really elevates the Black Myth: Wukong is the sheer density of it. Much of the production (although not polish) is on par with some of Sony’s best first party titles, but no part of it feels extraneous or watered down. You fight more than 100 bosses in the game, and a shocking percentage of them are not repeated. The ones that are repeated are done with good reason. Creatures and characters from the original novel are not only rendered and interpreted faithfully down to minute details, but every one of them has a dense, Final Fantasy XII style bestiary illustration and lore entry complete with poetry. Elaborate in-game animation and motion capture, fantastic voice acting, and wildly creative choices are around every corner. The headless sanxian player, played by Xiong Zhuying, is one of my favorite cameo characters in a long time. The elaborate anime segments between chapters, done by accomplished animators like Chengxi Huang and Hiromatsu Shuu, are jaw-dropping not only in their complexity, but in the way that they add to the backstory in a way that is parallel to the plot. Each one is unique, often animated in entirely different styles and mediums, with each feeling incredibly distinct. It’s like if you put an Animatrix-tier animation anthology in the middle of a Final Fantasy game. Even the way the game’s combat fuses existing gameplay conventions with new behaviors plucked right from Sun Wukong’s story is shockingly innovative. I can think of some games that do some of these things well, but none that do all of them well.

The more I played Black Myth: Wukong the more I was struck by its sheer ambition. For more reasons than are expedient to reiterate, blockbuster games have felt stagnant, broken or conventional lately. The ones that are operating at this level are often coasting on a prior success or are severely half-baked. Black Myth: Wukong is something new, huge and unique – a AAA non-gacha success story out of China that, though imperfect and messy in its release, does what it does well and is worth taking seriously.