COVID has hung like an albatross around Death Stranding’s neck since lockdown. The original game was released, almost prophetically, at a time when people were exclusively connecting online, akin to the chiral network that players are tasked to complete. Like 9/11 and the social violence of misinformation on the internet in Metal Gear Solid 2, Death Stranding accidentally wielded The Lathe of Heaven more powerfully than it ever had before in any Kojima-directed game. But being anchored to a physically and mentally traumatic event that everyone on Earth experienced is a difficult thing to build a sequel on. Kojima himself has said in the 2022 announcement that Death Stranding 2 was already written prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but that he rewrote the entire thing from scratch following that experience.

“I also didn’t want to predict any more future, so I rewrote it” Kojima joked at the 2022 Game Awards through a translator. The trailer ended with the uncertain tagline: Should we have connected?

It’s a strange thing to call a Kojima game “breezy,” let alone the follow up to Death Stranding. But there is a simple joy that permeates Death Stranding 2: On The Beach: winking fun that, while present in the man’s entire career, is now fully unleashed like an unruly dog. In Death Stranding 2, Kojima is having a blast. It is a joy that I find infectious, and the correct choice tonally given everything that the first Death Stranding had come to represent.

When Death Stranding 2 was announced it was done in a shockingly straightforward way. While there were hints of its development, none of the normal puzzle box horseshit that Kojima pulls was on display here: no mummified Joakim Mogren, no fake severed USB drive arms, no beguiling trailer hidden inside one of the best short horror games ever made. Just the man stating in a matter of fact way that they were making another one of those, and asking, are you ready for more? I wasn’t sure, given the bloated ending of the original Death Stranding. But the ease of that simple announcement belied a sensation that has carried through the entirety of my second playthrough, a commitment to lean into the things that were fun in the first game and throw out or tweak the things that weren’t.

“The blues they send to meet me won’t defeat me”

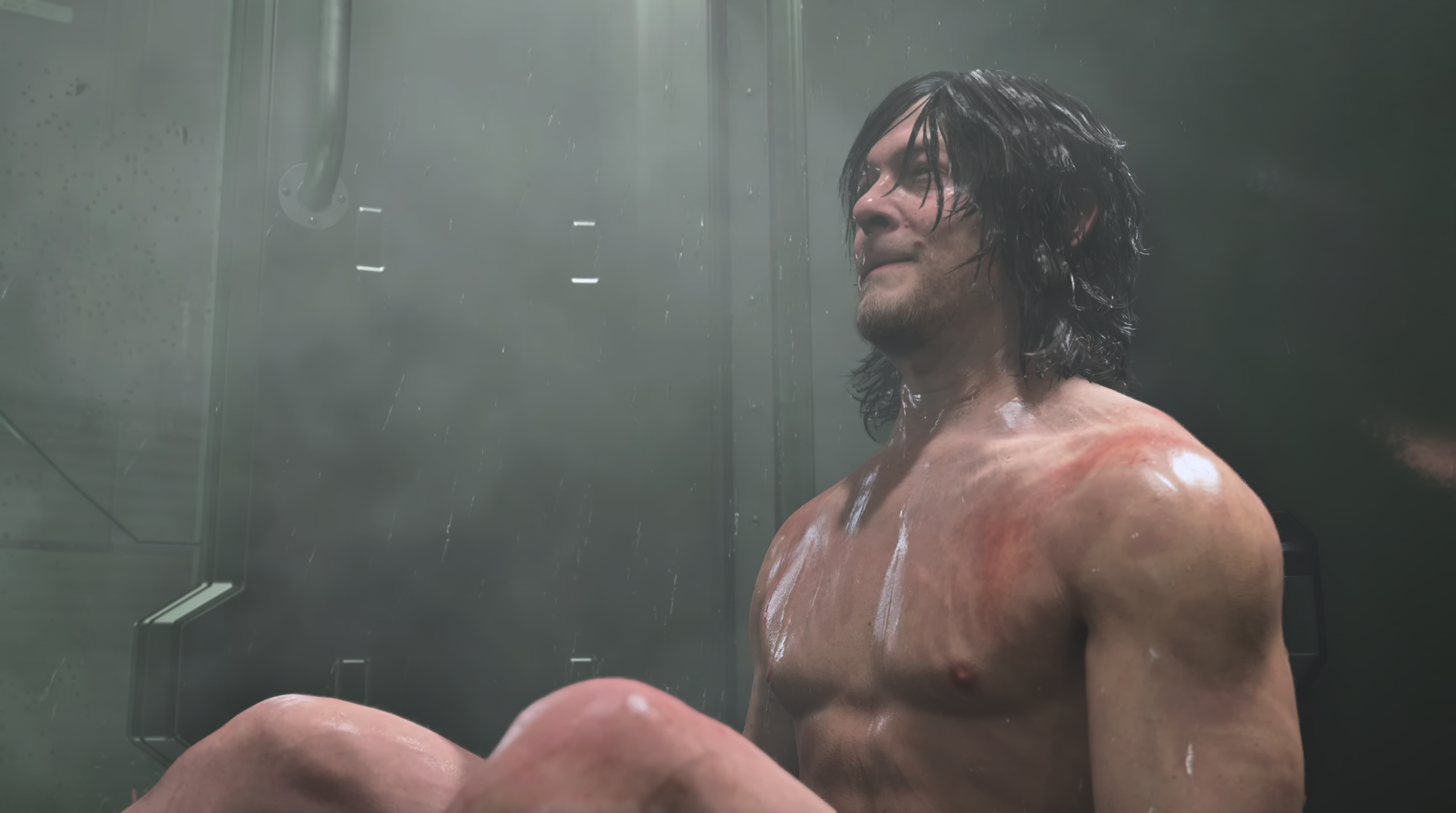

Death Stranding 2 picks up following the events of the first game, with Sam (played by Norman Reedus) raising Lou (aka BB-28) in a shelter near Mexico. Lou is now a toddler, and Sam is a doting single father. Fragile (played by Léa Seydoux) enters into Sam’s life once again, trying to get the legendary porter back into the game to help connect Mexico to the Chiral Network. After getting back into the swing of things tragedy strikes, and Sam goes back to his old ways as a means of just moving forward, this time connecting the continent of Australia to the network.

It is not particularly easy or illuminating to summarize the events of the first Death Stranding, although the game does have a rough summary of what went down in case it’s been a minute. It is unfortunately a game that requires, bare minimum, binging a big Youtube compilation of the cutscenes if you haven’t played the first. It is also a pointedly similar game to the first one, with the same core gameplay loop and boss structure.

Sam still schleps between unconnected shelters and bases like the most daring deliverista-slash-FIOS-technician (his job itself a modern interpretation of Japanese porters known as Bokka). You are rewarded with new tools and resources by increasing the connections between people, and those resources can be then invested into building the infrastructure of the world in the form of roads, buildings, monorails, and now mines. You also will have to fight an occasional big sloppy field boss fight (which can be straight up skipped) or a series of complex boss fights akin to the Mads Mikkelsen fights in the first game, with the Clifford Unger character instead being replaced by Luca Marinelli doing his best impression of Snake from Metal Gear Solid.

I have seen the game called iterative by some and “the same game” by others. I think the first part is technically true but misses the point and the latter is a little uncharitable but speaks to something important. Namely, that the quality of life improvements in the Director’s Cut and the global brain damage of COVID can make it difficult for anybody but diehard fans to parse what is actually new in this game. But I should be clear that Death Stranding 2 is categorically a better and more enjoyable game than its predecessor. The first Death Stranding took its sweet time to get off the ground, whereas Death Stranding 2 comfortably shoves you into what would normally be the midgame, with vehicles and weapons given to you early.

Combat in the first game was largely something to be avoided, lest killing an NPC cause what’s called a voidout—a giant temporary crater that happens in the universe when a dead body is not properly disposed of. Death Stranding 2 tacitly acknowledges that, while interesting, the experience itself of avoiding combat wasn’t as fun as going clown mode on a base of baddies. Weapons are implausibly non-lethal by default now, and the game just throws more tools than you can handle to deal with enemy threats. The grenade launcher is an MVP, and I found myself using it as a “get out of jail free” card in tough situations, but I found myself preferring melee whenever possible. There is an argument to be made that the game is “too easy” (I disagree with this a little when you hit the big ass mountain), but to me the game hews closer to the large open world of Metal Gear Solid V, a game that I feel has been more harshly reappraised in the years since its release but one that I still find a joy to play.

I thank my lucky stars that I did not have to review this game under embargo. Death Stranding 2, like its predecessor, is a game that is not structured to be rushed. There is an even greater emphasis on infrastructure this time around, and the decreased stress of every interaction gives it an almost cozy feeling. I refused to continue in any story mission until a road to that destination had been at least halfway built, and by the time I hit credits I had built every road and monorail, restored every mine, found every base, and built what was functionally a zipline ski resort on top of the one giant snowy mountain that takes up 50 percent of the mass of Australia. I clocked over 90 hours in the game, and at no point did I tire of it.

“Something special, just for you.”

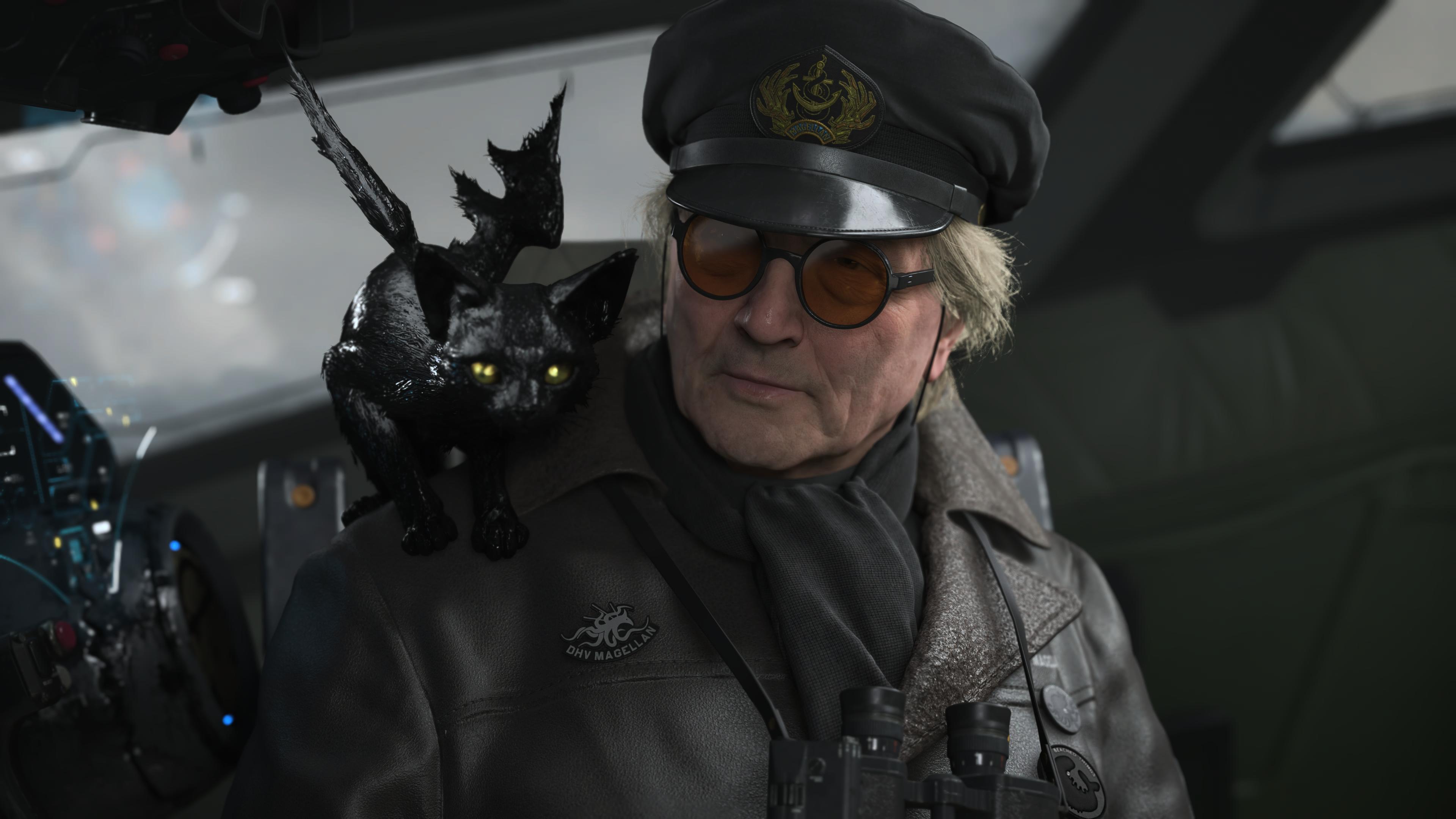

On top of more enjoyable combat and a breezier, meditative pace that rewards slowly building out infrastructure, the game sets as the focal point the DHV Magellan: a ship traveling on the tar currents that connect the metaphysical and physical planes of existence. As the game goes on, the ship collects characters from the previous game as well as newly introduced ones, including the captain Tarman whose likeness is based on Mad Max director George Miller. This conceit is the beating heart of the game, as characters are no longer isolated individuals trapped in their respective spaces, but friends and comrades working towards a common goal.

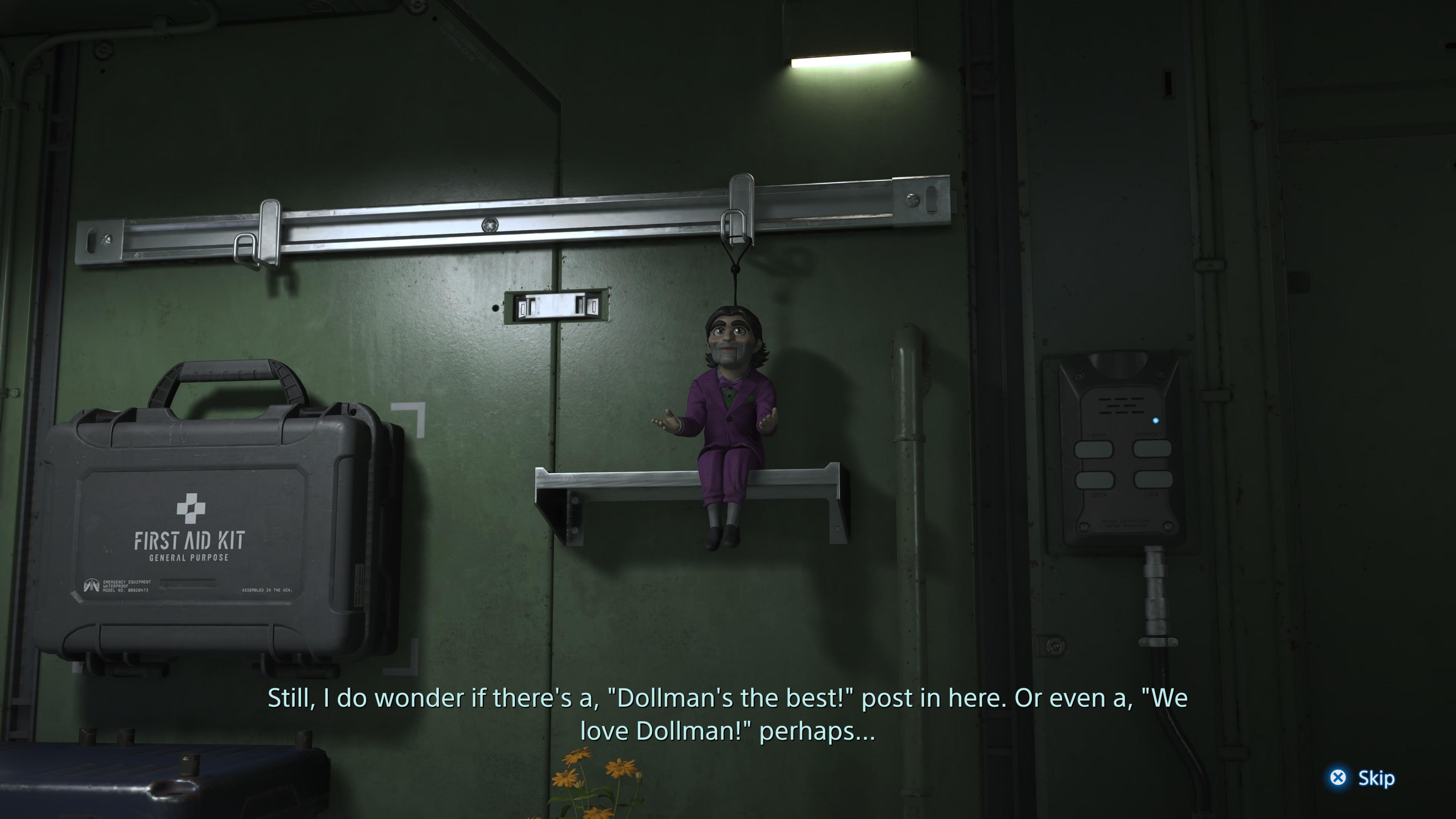

Of all the new cast members, the one you interact with the most is Dollman. Dollman is a guy whose Ka, or soul, was trapped inside a doll. His body moves in a troubling, jerky way which makes him appear as though he is animated via stop motion. He also serves the same purpose that codex calls in previous Kojima games; a means to keep the player on track with the most obnoxious and obvious exposition humanly possible.

At first this made me deeply loathe Dollman, but I am pleased to report that I was wrong. Dollman rocks. He’s like if Jigsaw’s puppet Billy was your homie; a chipper bit of positivity and a more enjoyable vehicle for information. When the game lets you know that you can chuck his ass into the air and use him to scout terrain or enemy encampments, I was fully on board. We love Dollman.

Dollman gets to the center of what makes Death Stranding 2 distinct instead of a route regurgitation of the previous game: it’s goofy as hell. Another prime example of this is the return of Higgs, played by Troy Baker.

I cannot stress how much Higgs sucks in the first game. It’s not that he was simply repugnant, he was irritating too. Well now he’s back, he’s worse, and that was absolutely the right move. Higgs in Death Stranding 2 is a queeny-cyborg-cowboy-ninja who is constantly chewing the scenery. I believe it was Ian Broudou who pointed out that he’s basically that one dril tweet that goes “the jduge orders me to take off my anonymous v mask & im wearing the joker makeup underneath it. everyone in the courtroom groans at my shit.” Troy Baker is clearly having the time of his life hamming shit up, and both this and his uncanny Harrison Ford impression in the MachineGames Indiana Jones video game have elevated him as an actor in my personal esteem. A jarring amount of pathos is yanked out of him in the final act, an incredible feat for a character that’s basically every Jared Leto acting impulse shoved into one weird robot.

The thing that I cannot shake from my time with Death Stranding 2 is how everyone involved is clearly having a blast. I have not seen a game in Kojima’s orbit that’s so much fun since Metal Gear Rising: Revengence, which is convenient because that’s my favorite Metal Gear game. The last four hours of Death Stranding 2 are some of the most absurd spectacle the man has ever been associated with. Kojima is constantly mugging at the camera through his characters, leaving silly, obvious references to his previous games as if to suggest that even he thinks it’s a bit absurd. Inhabiting the space often feels more like you are inhabiting Kojima’s instagram feed, like he’s gotten all the actors and directors that he personally enjoys together, put them in his weird little scanner, and he’s smashing them together like little action figures a la Rick Moranis in Space Balls. It is like he has reassessed his life, discarded the bullshit he’s tired of, and emphasized the stuff that he really loves.

“You of all people should understand. The loneliness.”

This is also one of the few times that I have played a Kojima game that feels ruminative instead of attempting to predict the future. Norman Reedus’ physical performance is notably haunting, conveying with his presence a man who has collected more hurt than he can bear. There is a clear message from the beginning that, as Sam enters Mexico over the rusted ruins of Trump’s border wall, the United States is a cancer on the world whose entire existence is extractive and violent.

Kojima’s metaphorical usage of pregnancy is still fairly sloppy and many of his characters are gender essentialist in ways that Maddy Myers does a fantastic job of cataloging, but I do appreciate that he leans much more heavily on the ways in which the state sees pregnant people as a purely extractive resource with little regard for their safety. And while he has yet to write a woman in his games as complex and self-assured as The Boss in Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, there are times where you can see him getting closer to that again.

But the more I think about the game the more I cannot see it beyond the albatross of COVID. It is an unprecedented scar we all carry with us that we have neither the strength nor the patience to interrogate any more. Death Stranding 2 swims in the various ways that experience hurt us: children were raised wrong with years of their childhood erased; people were pushed to mental oblivion in a state of lockdown that was neither alive nor dead, the state and capital have extended their grasp with violence and repression; and workers were forced back on the job without being given a chance to assess what had broken inside off them.

For all its goofiness, Death Stranding 2 is one of the few pieces of media to point out, if only obliquely, that every person on earth is damaged goods now. As Higgs, a former porter, mockingly screams repeatedly in a paroxism of pain at one point “I’ll take the damage and the goods. I don’t break that easy.”

“The physical sensation of movement is something that we all crave. That unity of body and soul.”

When lockdown finally loosened a few years ago, I noticed club music had changed. Places that had previously played mathematically dire Berlin-style techno suddenly shifted their tone, and people started playing sets that were goofy and fun, often full of aggressive breakbeats like a Toonami ad break. Nobody wanted to be reminded of the drudgery that came before, being trapped in the coffin of your own home. Everyone instead wanted to be present and alive in a physical space with people again. This needed to be fun, and we needed to be surrounded by people in a physical space.

“We survived the pandemic because of the internet and the fact that people were about to connect online. Now there are people who work for our studio from home and whose faces I don’t even know.” Kojima said to Wired in June “Live concerts were canceled, and everything moved to online streaming. I understand that it was inevitable during the pandemic. It was the same with school. Instead of playing with friends or learning from teachers, you watched a screen, as if you were watching a YouTube video.”

Kojima also credits the trajectory towards the (now failed in one sense) Metaverse as an inspiration “Communication between human beings shouldn’t be like that. You meet people by chance and see unexpected things. With the path we were on, all of that would be lost.”

Death Stranding 2 is the only game it makes sense to make when you are associated with something of that magnitude. AAA titles take a little longer to cook up than DJ sets, but the same impulse is there. It is a goofy, soothing, and occasionally introspective game about coming together with friends and family to heal. It is about being alive and physically present again in spite of an increasingly hostile world. And though it is often overwrought, lumpy in its pacing, and recursively referential, it is the game with a heart that is lighter than a feather, an oddly cozy game to play, a balm to a weary soul, and by far the most human thing that Hideo Kojima has produced in ages.