I deeply regret not playing Slitterhead sooner. I was excited for it before release despite not knowing what it was exactly, and when it came out in November the reviews were divided. This can mean a game is deeply flawed, exceedingly abrasive or both. Slitterhead is both, but more the latter than the former for me. It’s an imperfect game that takes wild swings in gameplay not seen since the PS3 era and one that, like Kunitsu-gami, feels like it should not exist. Slitterhead kinda rules.

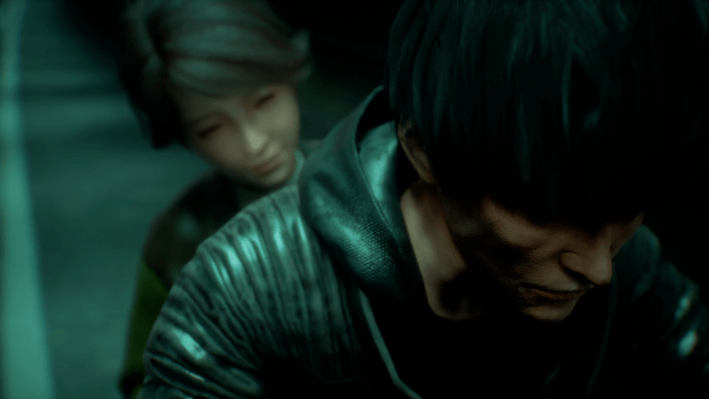

Slitterhead is the product of Keiichirō Toyama, the creator of Silent Hill, the Siren series and Gravity Rush. That is an incredible pedigree unto itself, and you can see the DNA of those titles in this one (particularly Gravity Rush which I was not anticipating). The game takes place in a fictionalized 90s Hong Kong and more specifically a version of the Kowloon Walled City called “Kowlong.” You take the form of a possessing spirit that comes to be known as Night Owl. You have no corporeal form per se, but instead control the bodies of regular citizens, using each person as a jumping off point and utilizing the power of their blood to form makeshift weapons.

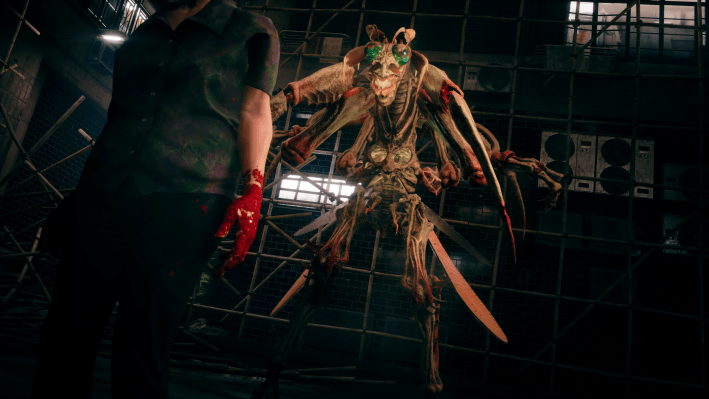

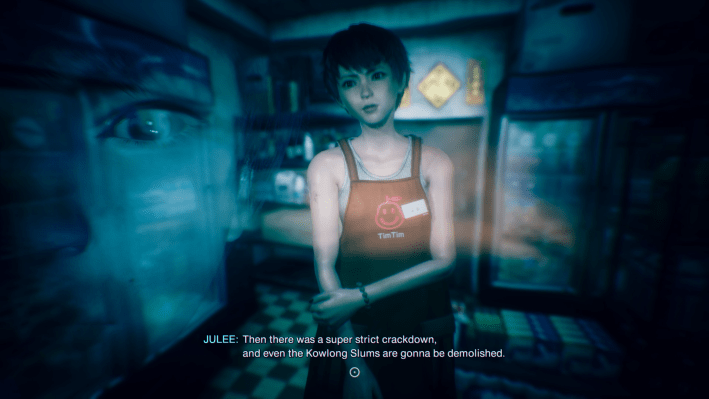

Hong Kong is being overrun by parasitic insect creatures known as slitterheads, which inhabit the bodies of otherwise normal humans and burst out of their skulls to feed on brains. Your goal initially is to hunt them down, although your memory of who you were and the events previous to the game remain foggy. What’s more, the slitterheads’ motivations are unclear. As Night Owl progresses through the game he becomes acquainted with special humans known as “rarities” who resonate particularly strongly with his power. These characters each have their own playstyle and add up to something that resembles your party. They exist as both the source of exposition in the plot well as the primary way you build your skills.

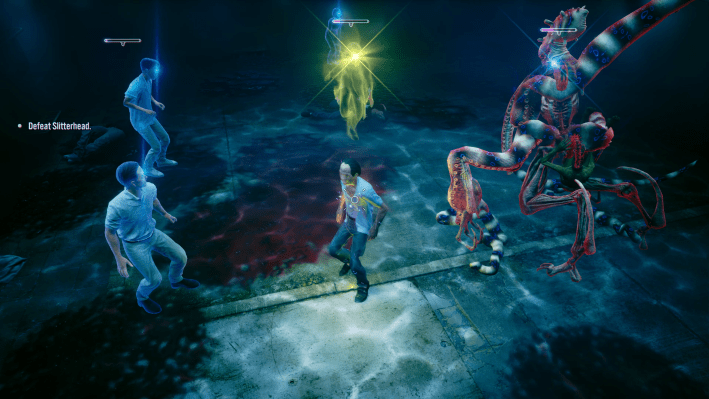

Combat in Slitterhead is a process of jumping between civilians and rarities, juggling the unique ability cooldowns of your characters and using the ability to shift rapidly between characters to confound foes. In addition to this, the ability to shift between characters is often used to hunt slitterheads, solve stealth puzzles, and rapidly jump though the dense, vertical terrain of Kowlong. When I said it most closely resembles Gravity Rush, this is the reason.

If that entire explanation was a lot to take in, it’s because Slitterhead is structurally confounding and a difficult game to place, although its similarities to Siren and Gravity Rush are crystal clear if you’ve played them. If I dig deep enough, I can pull up other games it reminds me of, but it has been a very long time since I’ve seen a game that is so thoroughly itself. How would you even begin to describe to a friend how this game works? “Well it’s sorta like Phantom Dust but if it also worked like Messiah or Ghost Trick or the PSP-only Parasite Eve spinoff The Third Birthday, and there’s also some Prototype and Edge of Tomorrow thrown in there.” If you understood at least half of those words, congratulations: you’re statistically 40 years old and have a specific kind of taste.

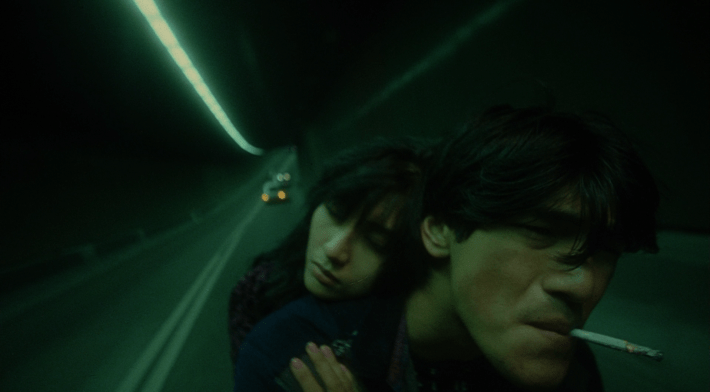

On top of all this, the setting of this game is straight up ripped from possibly one of my favorite eras in cinema — early 90s Hong Kong. This is very intentionally a Wong Kar-ai ass video game — in one of the opening cutscenes they literally recreate the iconic motorcycle shot from Fallen Angels. Toyama explicitly pulled from the work of Wong Kar-ai and Fruit Chan work when creating Cowlong. “I felt sad that I couldn’t get to witness that chaotic aspect from the 1990s.” This game is like Durian Durian meets Yakuza: Dead Souls. There is a close, lived-in density and lushness to the setting that is just so satisfying to inhabit. On top of this, Silent Hill composer Akira Yamaoka did much of the soundtrack, and it is one of the most varied and interesting works he’s put out in a while. There’s tracks that just sound like menacing burps. One track is just a noise band screaming in Cantonese, it rips.

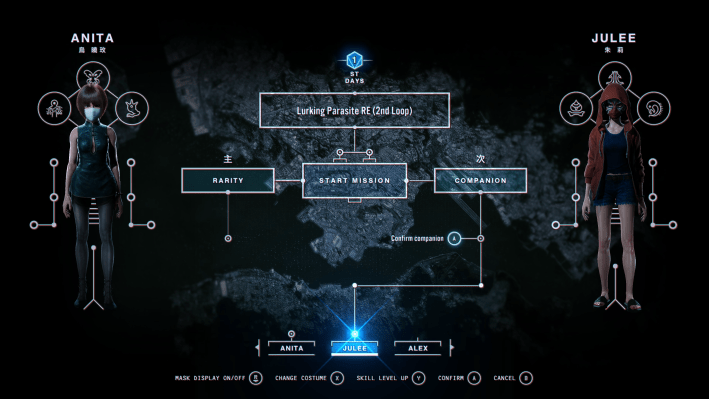

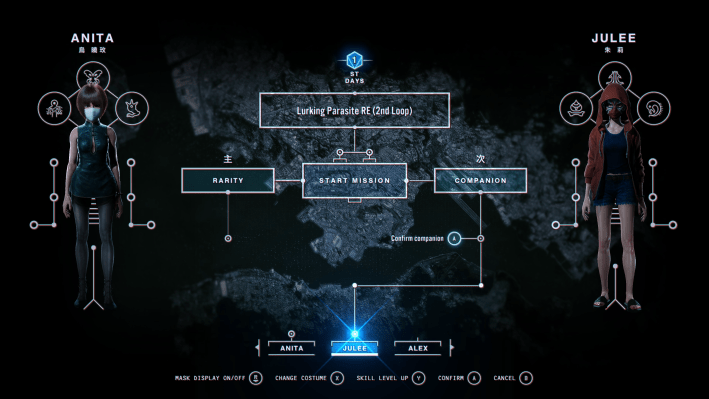

Oh, also the entire thing is a time loop story. In addition to having multiple characters you talk to between levels to progress the story, the game takes place in a three-day time loop, a tiny bit like Majora’s Mask. By returning to those previous days you change the fate of characters, recruiting new rarities and opening up new potential timelines. This involves replaying previous levels and using context clues from your rarities to find new paths in previously-explored missions. This quirk is both one of the game’s most interesting conceits and is also tied to its biggest flaw: repetition.

I love this game, but even I will agree with its harshest critics that it overextends itself. Not only does it repeat levels by design, but the core loops of the game are too similar from level to level. There's just not enough variation for the story it’s trying to tell, and as a result it overstays its welcome, sometimes to a grueling effect. That repetition can be exacerbated if you don’t know what tiny thing in a repeated stage you are looking for. If you don’t enjoy the game’s core combat, that would make playing the game feel like torture, but I love how this game feels on a base level. Cutting off a fleeing slitherhead by jumping into the body of a Chinese grandma like Agent Smith from The Matrix and clubbing it with a blood mace can wear a little thin after a several dozen times, but the actual sensation of doing it is so satisfying. What’s more, slitterheads are all fairly similar in a functional but not stylistic sense, which adds to a degree of monotony.

And yet, I found the combat in this game so unique and enjoyable that I was fine with that repetition through most of the game. The combos themselves are shockingly simple, but how the game manages moving in space is where the complexity lives. Blood is your main source of power and health in this game, and so fighting becomes a complex dance of managing that resource among all available characters and shifting perspectives to do health management. You mainly restore blood by sucking it up from pools on the ground. There is a parry system that involves using the right thumb stick while blocking to build up “Blood Time,” and while it has a tendency to halt the flow of combat, it makes it possible to dig yourself out of a hole if things are going south for you.

But what makes the game truly complex is the rarities. The cast of characters in this game are aggressively normal people — a sex worker, an unhoused alcoholic, an Indonesian housekeeper, a sexy doctor who chain-smokes. Each of them comes with a different perspective on the slitterheads, and each has a wildly different kit. Edo the unhoused man plays like a glass cannon monk type. Anita, the sex worker, can summon civilians to the area. The cool doctor has a shotgun made of blood and can turn any character into a living bomb. A max of two rarities can eventually be taken on missions, and one of their abilities can be extended to civilians, so synergizing playstyles between rarities becomes a vital but also personal choice.

If I am being effusive, it is partially because we do not get a lot of games this weird. When people bemoan what old games used to be, they are not actually harkening back to an aesthetic but an ecosystem. The PlayStation has one of the greatest libraries in history because there’s a lot of weird choices on it. There will always be blockbusters and struggling indies, but there used to be much more room made for middle budget games that colored outside the lines a bit. Both Slitterhead and Kunitsu-gami are in that lineage, and they both take clearly limited resources and stretch them as much as humanly possible.

I am not the first to notice that Slitterhead feels like a PS3 game fell out of a time portal. It has the soul of an untranslated UMD that you had to import for $90 in 2006 cash. It’s the kind of title that Microsoft would commission and send out to die in Japan in an effort to sell an additional 20 Xbox 360s. This is a game designer’s game. Slitterhead is Dead Rising and Godhand and Chaindive and Boktai and Rule of Rose and Bullet Witch and every little freak game that sticks in your craw while so many games with dangerously large budgets pass through you fully undigested. It exists unstuck in time and beyond the binaries of good or bad reviews. It is an ambitious love letter to a Hong Kong of yesteryear that resists categorization and is wholly itself. It is not perfect, nor does it need to be. It deserves to be studied and dissected like a rare beetle because games anywhere close to it are in shockingly short supply these days.