It’s hard to think of a more iconic opening sequence in RPG history than the intro of Final Fantasy VII. After a CG cutscene that was groundbreaking in 1997 and still slaps today, the game quickly makes its intent clear: the player is here at Midgar’s Sector 1 Mako reactor to do terrorism.

This article contains spoilers for the original Final Fantasy VII, FFVII Remake and FFVII Rebirth

The explosive sequence that follows sets up the game’s initial conflict between the planet-killing capitalists of the Shinra Electric Power Company—who are literally extracting the world’s life force for profit—and Avalanche, a resistance group clearly modeled after real-world environmental activists like the Earth Liberation Front (ELF). But unlike many games released at the time, FFVII starts off by firmly establishing the eco-saboteurs as the good guys.

The game’s main conflict has been on my mind while watching university students protest Israel’s ongoing attacks on Gaza. The protests emerged on campuses across the country several months after the release of Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, and while I normally find it cringe to reflect on real world horrors through the lens of video games, the timing of the uprisings—and how they’ve unfolded—made it impossible for me to ignore the political impact of the original FFVII.

Nearly everyone I’ve ever talked to who played FFVII growing up has told me that its opening scene was a pivotal moment in their political awakening. In 1997, the idea that militant insurrection is sometimes necessary to create political change hadn’t really been explored in a major video game before. Even those that dallied in the topic hadn’t so viscerally placed players in the role of protagonists engaged in violent resistance, or made clear why they believe these actions are moral and justified.

In the 80s and 90s, the ELF’s militant actions included sabotaging industrial equipment and defacing corporate property, causing material and economic damage to those responsible for environmental destruction. This made them one of the first groups to be targeted by the US government as so-called eco-terrorists, inspiring the “Green Scare” and new laws that later became the framework for the government’s ever-expanding “War on Terrorism.” There was debate at the time over whether or not the methods of these groups were effective or too extreme. But in FFVII, the stakes are made clear: The planet is literally dying, and blowing up a reactor whose sole function facilitates this ecocide is a practical and material response to avoid, or at least delay, a world-ending global cataclysm.

My goal here is not to compare a fictional resistance struggle with Palestine’s 75-year anti-colonial struggle or with the international movement that has risen in support of it. But as a Jewish woman who used to identify as a hardcore, pro-Israel Zionist, replaying FFVII’s story via Remake and Rebirth has made me realize how deeply this game’s ideas resonate—and how many of them went completely over my head as a kid.

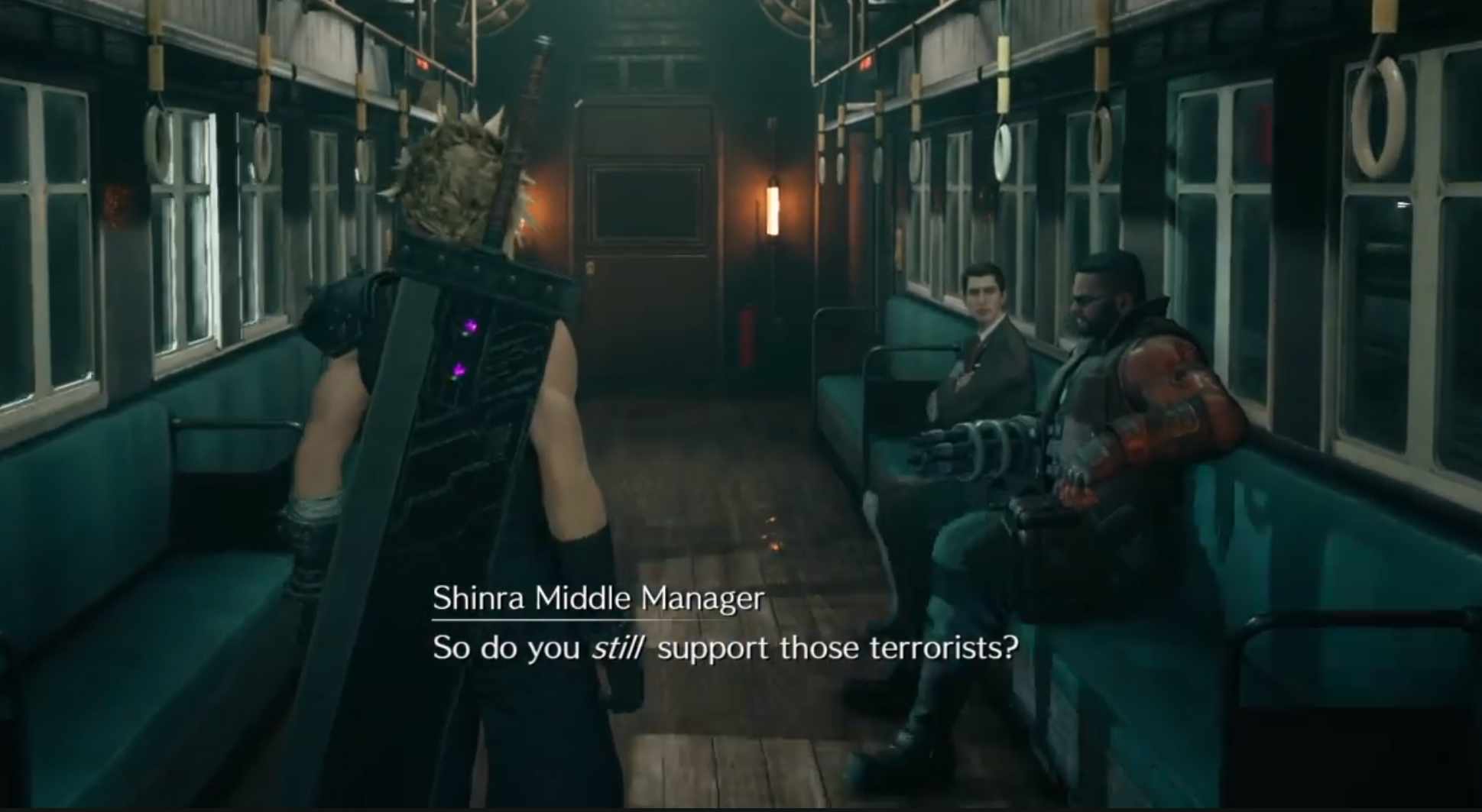

A common criticism goes like this: Many people empathize with the goals of fictional resistance groups like Avalanche, but can’t seem to connect the dots when it comes to the real-world resistance struggles they’re based on. This has always fascinated me. FFVII not only forced players to consider the righteousness of militant actions, but illustrated two of the most important ways that real-world governments historically respond to them: first, by using the media to scapegoat and smear resistance groups and their supporters, and second, by enacting disproportionate violence as a form of collective punishment.

This allows the state to project the consequences of its own violent excess onto its political enemies, thus justifying further violence against them. Shinra’s destruction of Sector 7 in the original FFVII is the most obvious and extreme example, but Remake takes this a step further, changing the story to show that it was actually Shinra—and not Avalanche—responsible for the deadly aftermath of the reactor bombing in the game’s opening. Monsters—which Shinra protects some, but not all, of its citizens from—are also a result of the company’s experiments to create biological weapons of war. Even Sephiroth, who fully replaces Shinra as the game’s main antagonist in Rebirth, is a living reminder that the apocalyptic crisis the world faces is a direct result of a fascist government’s insatiable greed and colonial ambition. Without Shinra, after all, there would be no Sephiroth.

Characters on the pro-Shinra side, meanwhile, describe the company at best as a necessary evil. The power of Mako quite literally keeps the lights on in Midgar, and most citizens can’t imagine living without it. This always reminds me of something I was taught early on in my Zionist education: the idea that a powerful nation-state is necessary to ensure our safety. I was taught that violence done in my name—the details of which were often omitted or obscured—is unfortunate but justified. Like many young Jews, I learned about the Holocaust from a very early age, and this was all the proof I needed to know that our comfort and way of life—our very survival as Jews, I was told—was at stake.

It wasn’t until later in life that I began to see holes in this narrative, which weaponizes generational trauma to manufacture consent for state violence. It started by reading the many historical examples of resistance groups, and how they’re often painted as criminals and terrorists who seek only to destroy the average citizen’s way of life. We’ve seen that narrative a lot in recent weeks, as police and university administrators inflict violence on students protesting genocide while demolishing their encampments. The news media and politicians use their platforms to snarl at students and their allies, calling them “outside agitators,” “terrorists,” or worse. In early May, President Joe Biden admonished the student protesters, declaring that “order must prevail” and stating—ahistorically and without a hint of irony—that “dissent must never lead to disorder.”

Such declarations rarely, if ever, stand the test of time. The “order” that Biden is demanding is the very same that Martin Luther King, Jr. excoriated in his Letter From Birmingham Jail, where he famously described “the white moderate [...] who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” The “negative peace,” in this case, being the comfort of school administrators and pro-Israel faculty amidst a complete absence of safety and justice for Palestinians in Gaza, where every last university and approximately 62 percent of homes have been destroyed by Israeli occupation forces, using US weapons and funding. As always, those calling for this “peace” are in reality calling for a status quo that prioritizes their feelings of comfort in the imperial core over the lives of those who suffer the violence of the state.

Those condemning the protesters also use the predictable and age-old tactic of declaring pro-Palestinian demonstrations “antisemitic.” I’m intimately familiar with this narrative, because I was taught it as a teen. The explicit goal is to conflate any criticism of the Israeli state with hatred of Jews—something the US Congress is currently attempting to codify into law. This false idea attempts to justify an eliminationist campaign in Gaza that has already killed over 35,000 Palestinians, completely destroyed the majority of hospitals, and created an artificial famine by cutting off aid and medical supplies.

History shows us again and again that balancing the comfort and safety of one group atop the destruction and oppression of another never goes well for anyone involved. Those who cheer on state violence against resistance movements are not remembered fondly, and the extraction and exploitation of colonial powers eventually comes back to haunt those it was supposedly done to benefit.

Shinra served as an early guidepost in my understanding of how these oppressive powers think and act. Although the conglomerate falls into the background as a secondary rival throughout most of FFVII, every societal ill the player encounters can be traced back to it. In a polarizing scene toward the end of the game, Avalanche leader Barret Wallace does a surprising mea culpa, expressing regret for the group’s reactor bombing. This scene always struck me as good character development, but also forced and awkward. While Barret and crew wouldn’t be the good guys if they didn’t care how their actions might harm others, the speech seems to miss the bigger picture.

By forcing the planet to a point of crisis, Shinra guarantees the undoing of its world order and all the mess that comes with it, including Avalanche. When the very ideas of “order” and “peace” become cover for a controlled decline that inevitably leads to disaster, the only options remaining are to either accept that fate, or oppose it by any means necessary. We see glimpses of a reality that “has accepted its fate” in one of FFVII Rebirth’s multiverse timelines, where ex-SOLDIER Zack returns to Midgar as the last remaining Mako is drained from the planet. These are some of the bleakest scenes in the game, both because the citizens of Midgar have lost all hope, and because Shinra’s soldiers nonetheless continue to maintain “order” as everyone awaits their demise—an extinction event that Shinra itself has orchestrated.

Shinra may be a fictional world government from a video game about magical twinks with giant swords, but it draws vividly from a history of real-world imperialism. That history shows us that sometimes, states must be pushed to the brink in order for any real change to occur. Before being assassinated by Israeli forces in 2017, Palestinian activist Bassel al-Araj wrote, “The beginning of every revolution is an exit, an exit from the social order that power has enshrined in the name of law, stability, public interest, and the greater good.”

This “exit” is necessarily destabilizing and scary, and no one’s safety can be guaranteed during the struggle that ensues. But the only alternative to building a better world in the unknown is to accept the world we’re already in—calmly waiting until the Lifestream runs dry.