Is it worth sticking with a bad job if you’re good at it? What if you aren’t? What does taking responsibility mean in a lawless place? Mouthwashing is an abrasive psychological horror game about jobs, leadership, responsibility, mental illness, and what happens when those things careen into each other with violence. It is often disgusting, occasionally touching, and one of the tightest narratives I have played all year.

Spoiler alert: Mouthwashing is about 3 hours long, most of which is narrative. This article discusses elements of the plot, some of which might be more impactful as a surprise. If you wanna go in blind, you have been warned.

Mouthwashing is a first person horror game by Swedish developer Wrong Organ. Four months have passed since the space freighter Tulpar was driven into a head-on collision with an asteroid. In the process the captain, Curly, was left with severe burns. The crew has four months of food left on the ship. Resentment and mental illness that were already present are starting to get worse. The situation is made worse by two revelations: that after this job the entire crew is going to be laid off by their employer Pony Express (implicitly in favor of automation), and that the entire reason for the voyage that stranded them was a cargo hold full of Dragonbreath X brand mouthwash.

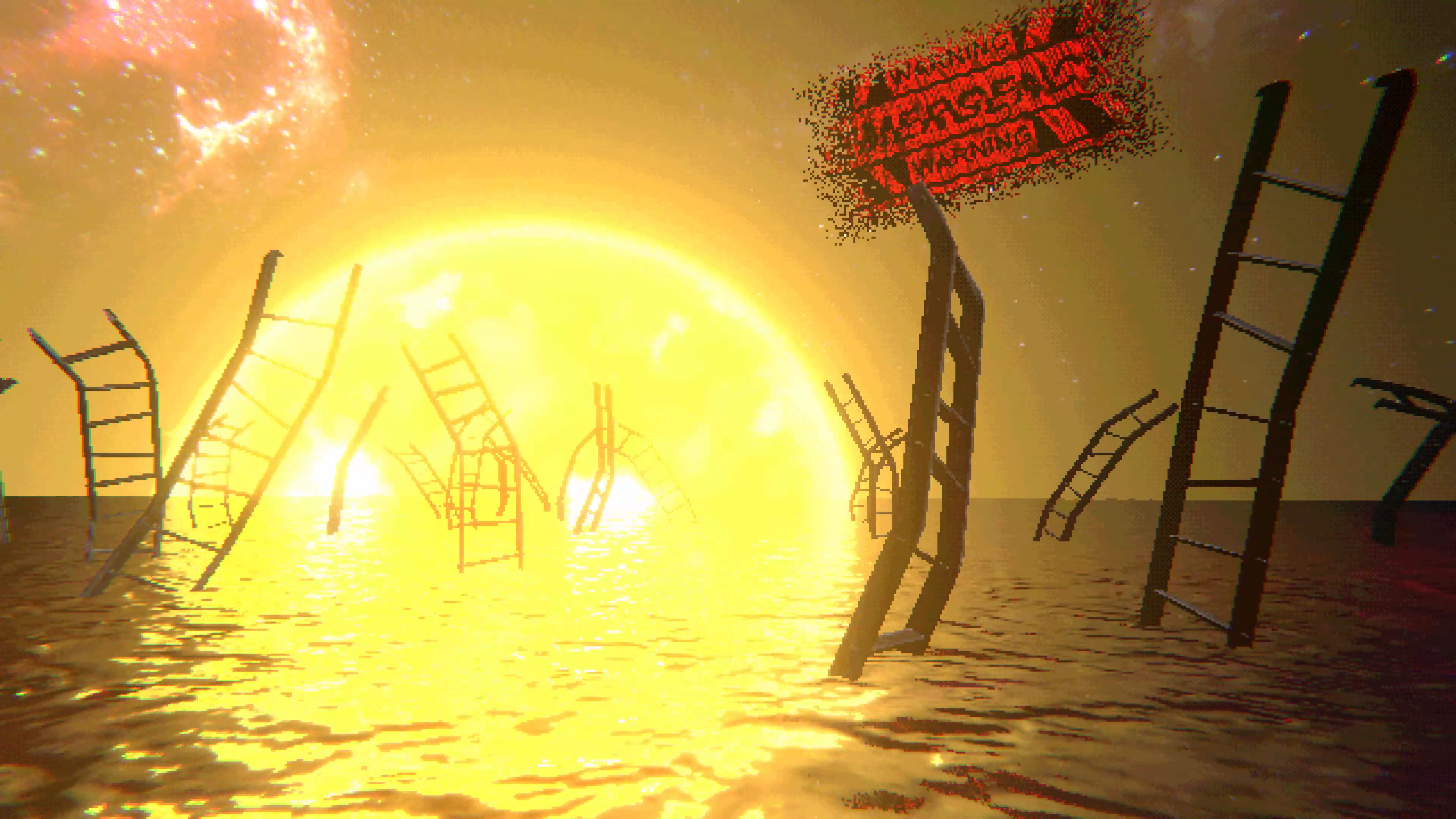

The structure of Mouthwashing is nonlinear, jumping back and forth between the perspectives of Captain Curly and his co-pilot Jimmy before and after the crash. These jumps take the form of sudden data moshing transitions and complex interactive dream sequences that serve as metaphors for the plot and collapsing mental state of the crew. Before the crash, we see the web of relationships that led to the ship being driven off course – Curly knows he is a good captain who can do better than this job but sticks with it because it is safe. Jimmy, his long time friend, slightly envies him for that.

After the crash, Jimmy takes over for Curly’s duties as the de-facto leader. Curly was heavily burned in the cockpit when the ship crashed. He is now unable to speak and heavily bandaged; only force-feeding him a slowly dwindling supply of painkillers will silence his cries. Other members of the crew are not taking it well either: The discovery of a mountain of mouthwash and impending mass layoffs prompts Swansea, an older man with a family and not much work left in him to break a 15 year sober streak and bully Daisuke, the gullible intern, into a dangerous and toxic drinking binge. Anya, the ship’s nurse, buckles under feelings of inadequacy and other severe health and interpersonal issues. Jimmy, now in the role of captain, convinces himself he can fix a situation that may not be fixable.

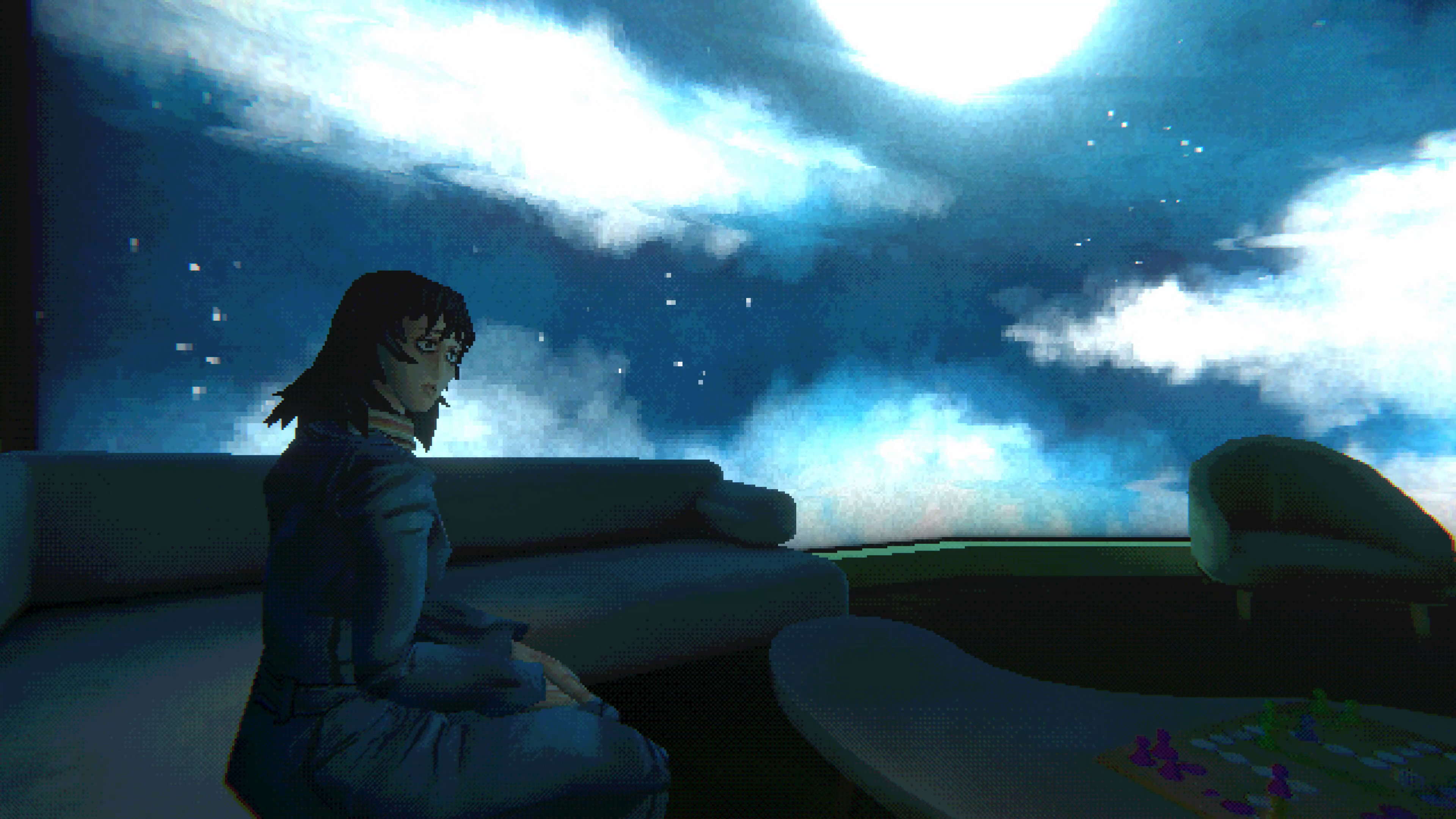

There are brief moments of hope in that despair, fleeting glances of interpersonal joy between the crew members. Swansea as a cantankerous grease monkey and Daisuke as the green intern have good chemistry early on. Jimmy and Curly clearly have built up a legitimate, albeit strained, friendship over the years. The Tulpar is filled with the bare minimum amenities for the mental health of the crew, which they still manage to enjoy. Pony Express has rationed a single birthday party for the crew which is joyous before it isn’t. In one flashback prior to the crash, Anya and Captain Curly stare at the wraparound OLED that imitates the night sky in the lounge, and she points to a dead pixel on the screen that she cannot unsee. “I have to believe that our worst moments don’t make us monsters,” Anya repeats often. The game allots you tiny rations of joy, so much to make starving to death feel worse.

Mouthwashing is of a piece with a lot of art I enjoy. It shares a currently in-vogue chunky PS1 style like the recent Artic Eggs and Crow Country, both of which I enjoyed. It is in the same tonal neighborhood as many of Kojima’s freakier stylistic touches in games like P.T., Metal Gear Solid 4 and Death Stranding. I was also reminded of the 2018 Swedish science fiction movie Aniaria and Claire Denis’ High Life from the same year, both of which deal with the violent and psychological consequences of being marooned in space.

But above all Silent Hill looms heaviest in my mind, appropriately timed given the upcoming remake of Silent Hill 2 by Bloober Team. Mouthwashing is a game about longtime coworkers and friends pushed to their breaking point, about the things we do to each other and what we think we owe each other. The people here are damned, like James Sunderland and everyone he meets in Silent Hill 2.

Mouthwashing is meant to leave a queasy feeling in the pit of your stomach, and it succeeds at that. Sometimes it touches its subjects with the subtlety of a sledgehammer – extended torturous sequences of cruelty that may be too abject for some to handle (although even an obvious metaphor rendered maximally can be effective). Other times it deploys itself with shocking nuance and humanity, gorgeous, layered storytelling that stays with you. But even when the experience gets too much to bear, it does so in a way that is narratively taut and stylistically jaw-dropping. You do not linger, and there is little fat in this narrative.

In many ways the experience is similar in size and shape to this year’s Silent Hill: The Short Message. Both games can be finished in one sitting, and technically do have puzzles, but only in a way to provide a slight interactive resistance to the player. But The Short Message, for all its faults, is fundamentally a far more compassionate narrative. There is beauty and hope at the core of The Short Message, particularly near the end. Mouthwashing is pure hell. I am sure that it will leave a foul taste in some people’s mouths, although that is precisely what it sets out to do.

There are severe depictions, both literal and metaphorical, of interpersonal abuse and self-harm, and while it could be argued that those should be signposted a bit better, I don’t think the game makers have a responsibility to pull their punches when engineering The Void. To quote Claire Dennis at a Q&A for High Life, “I am not a social worker.” Mouthwashing is a game about ambition, capitalism, and the delusions that people in power create for themselves to justify gaining and exercising that power. What does being a manager do to your soul, particularly when a role in management is often an economic lifeboat? And how many horrors stem from working within a system built on a foundation of exploitation and cruelty?

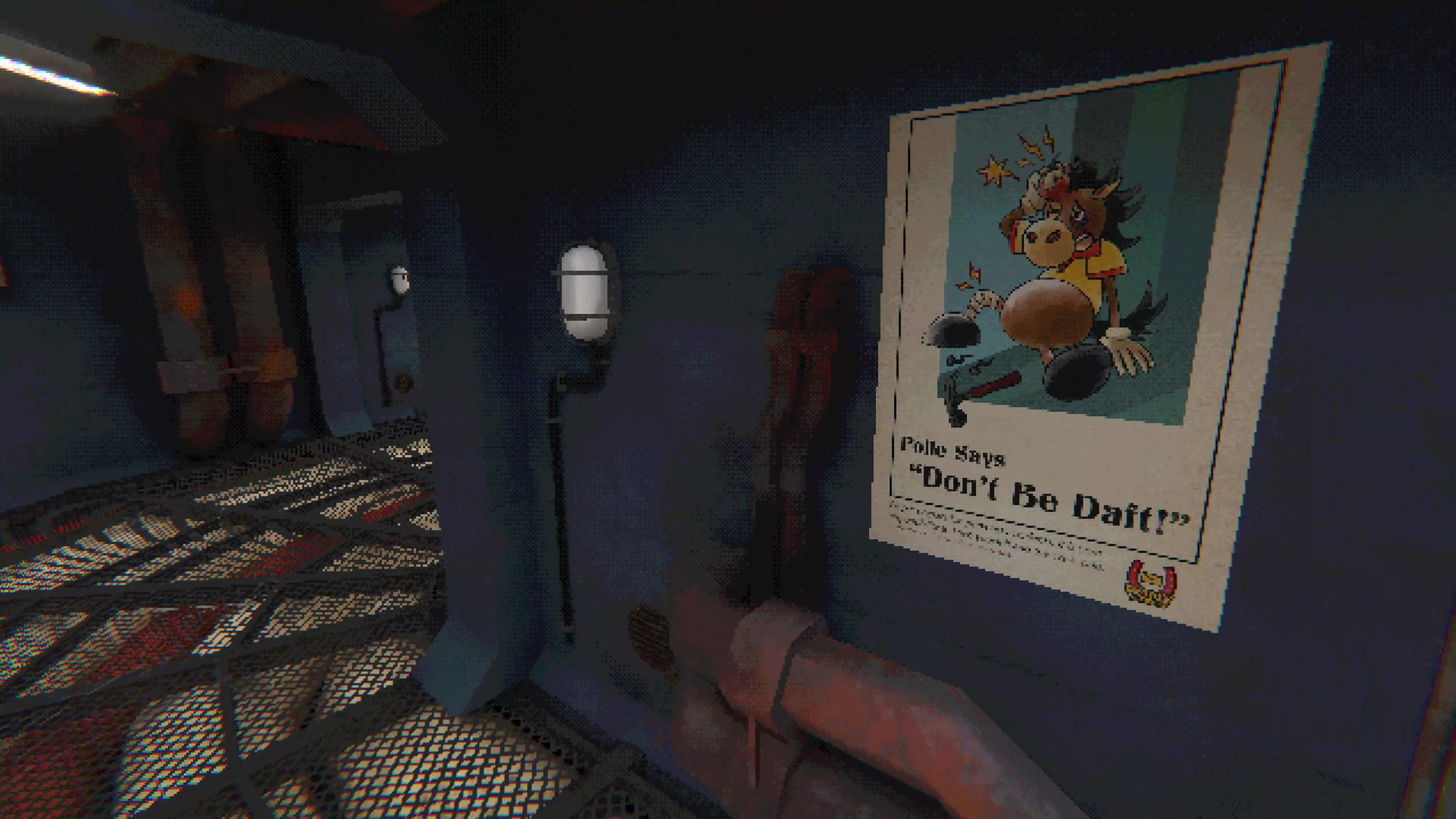

There is another recurring character in Mouthwashing outside of the crew, a garish generic pony mascot for the Pony Express company named Polle. His goofy face is plastered all over the ship’s safety posters, and a lifesize statue of him stands in the common area caterwauling to passersby, his eyes locked in a Five Nights At Freddy’s style rictus. During one of the many metaphorical dream sequences, you must slowly creep through a warehouse of crates of mouthwash to avoid being caught by a dragon-like horse monster. Though you can see him thrash, and indentations where his serpentine neck have crushed the catwalk, his body and face are invisible except briefly when viewed through a special blacklight given only to the captains of the ship. Your only hint in beating him is a single note at the beginning, but it also sums up the game quite nicely.

“A blind beast, aimless and restless. You can’t run from it.”