Releasing a free-to-play short game based on Silent Hill was always going to be a losing endeavor. The comparison to P.T. looms heavy in everyone’s mind as a link in trust that is forever severed. So, why did Konami make the short, free-to-play Silent Hill: The Short Message?

The Short Message begins with a still warning the player to seek help if they are at risk of self-harm or suicide. I will repeat that warning, since that is overwhelmingly a theme of this game, and one that you should be warned about before reading.

Self-harm and suicide are not an uncommon theme in the series, nor ones that I believe to be off-limits when contextualized correctly. The main character, Anita, awakens in an abandoned building called Villa in a town called Kettenstadt in Germany. Through a series of notes it is revealed that the complex is abandoned due to two economic shocks: the first was the 2008 financial collapse; the second was covid-19 scaring Chinese investors. Since then, the building has become the haunt of several local graffiti artists, but also the site of many teenage deaths by suicide. This premise is the most interesting part of the game – the concept that the twin shocks of 2008 and covid can haunt a place, creating an evil that can forever haunt you, is felt by most people. But what ends up following is a mechanically infuriating and clunky attempt to reconcile with the concepts of bullying, social media, and teen suicide.

-Spoilers for this game follow-Anita is searching for her friend Maya, who is a Japanese graffiti artist who has an obsession with cherry blossoms, to the point where her handle is “C.B.”. She is obsessed with how the cherry blossoms die at the peak of their beauty. If the symbolism was not clear here, another note politely explains the shifting attitudes that Japanese society has towards “hara-kiri”, suicide generally, how Westerners misinterpret the act often, and how the act originally was meant as a means of purging your transgressions from the world. Anita searches for Maya, but can only find the remains of her art, her sketchbooks, etc.. I will give them credit: this does look like a teenager’s graffiti you would find in a squat in Germany, which is to say nice but a little trite.

Much of the game focuses on youth, bullying and social media. With the subtlety of a freight train, we are exposed to imagery of bullying and self-harm. Anita has a history of depression, has taken medication, has previously attempted suicide or cut herself, and has a history of being bullied. She comes from an abusive home, or at least that is the memory we are confronted with. We see Anita remember the ways in which she is bullied for badly using social media. She is chided by others for her bad selfies. This part is fair game and true to life, although it is funny to play a game where Twitter is a focal point while the site is dying and functionally unusable because of bots. The concept of the internet as a haunted space that drives people to real harm is also fertile ground, but the game doesn’t do much with it that was not already covered decades ago by either Serial Experiments Lain or Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse. Mostly the extent of the social media critique is just Anita being mad that someone else has more followers, and texting her friends.

There are things this game does well. I kind of like the ending, in a weird way. The monster design by Masahiro Ito and music by composer Akira Yamaoka feel right at home, and I was happy to see the use of FMV in certain cutscenes in the game. More games should do this. As a preview for what the Japanese side of this Silent Hill reboot is capable of (to say nothing of the disastrous Silent Hill: Ascension or the Silent Hill 2 remake which looks, well, bad), there is more there than there isn’t. The game plays with interesting themes of recursion and looping, ones that thematically tie in to the ideas of suicidal ideation, although it is ultimately weak tea when weighed against P. T. or the best of the series. And just a reminder: you still can’t legally download P.T. – I would like to be able to do that again just for the sake of preservation!

Part of what makes The Short Message frustrating is the overt lack of subtlety and its mechanical clunkiness. The only substantial interaction you have with the game is to look at objects and notes, and to run away from the (well-animated) monster Scooby-Doo style. You could derisively suggest that this clunkiness is true to one facet of the Silent Hill experience, but The Short Message does not simply live within the shadow of Silent Hill, it lives in the shadow of P.T., one of the most mechanically interesting horror games in history, a beautiful puzzle box that it took the whole internet to solve, and a point of pain that many fans are still pissed off about.

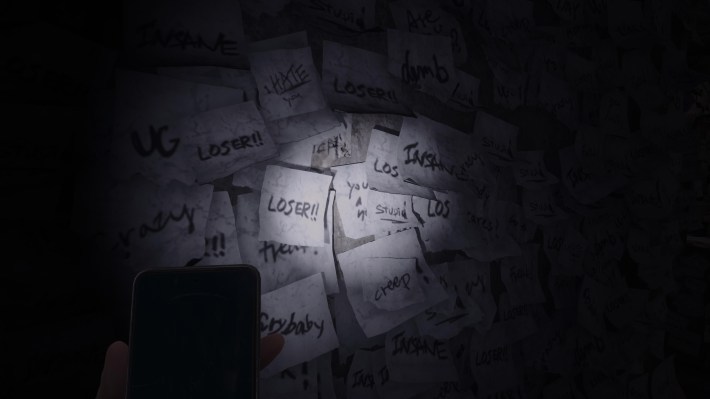

There’s groan-worthy images in this game, like a locker full of bloody razor blades and walls full of sticky notes with mean names written on them. The entire last boss fight, if you can call it that, is a frustrating hide and seek maze hunt that is less scary than it is irritating. The game also doesn’t come to satisfying conclusions to many of the threads that it lays down, which leads it to feel both forced in some ways and half-baked in others. At all times I get what they are going for, but the game is too small in scope to have fun, too obvious in the wrong ways and too frustrating in others. Multiple times I found myself saying “alright, I get it” out loud.

A recurring theme in The Short Message and much of Silent Hill is that of being cursed because you cannot acknowledge a wrong: that there is a fundamental transgression or sin that haunts you. Silent Hill is often depicted as a hell, a punishment zone that you will be trapped with until you can admit the sin you have shoved to the margins of your mind. Silent Hill as a series is also cursed like that. No company in gaming history imploded quite as spectacularly and publicly as Konami. They alienated a beloved game designer and put developers on janitorial duty in their gyms. It has felt perpetually strange for them to simply show up and pretend like that did not happen. And while I do not begrudge Silent Hill lead producer Motoi Okamoto or anyone involved for attempting to right the ship, this fact will forever haunt them like a ghost, chasing them, punishing them until they find a way to finally put it to rest.