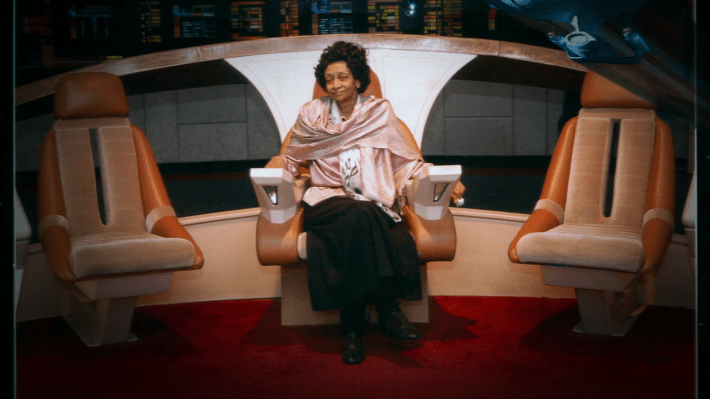

I love Chris Elliott. He’s a brilliant comedian whose legacy is often reduced to Cabin Boy, a good movie whose flaws are entirely the fault of Tim Burton for being a dipshit and screwing the production over. Elliot had two Cinemax-produced specials in the 80s, Action Family and FDR: A One Man Show, both brilliant high-concept specials that, for years, have existed exclusively as YouTube uploads with the worst quality imaginable.

Two years ago, I saw a screener tape with both specials and decided to transfer it. I finally put one of them online recently, but only after building an entire capture rig, modifying several VCRs and LaserDisc players, learning to encode video with python scripts, and getting into the most cutting-edge method of archiving VHS tapes and LaserDiscs: VHS-Decode and LD-Decode. And I did all this because I realized something that if nobody is going to preserve the films, shows, comedy specials, live television, and home movies that I love, then the person to do it has to be me.

Where has all the media gone?

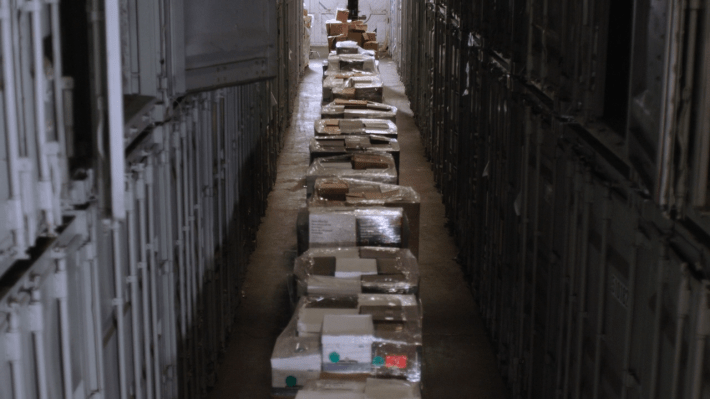

Before getting into preservation generally, it’s worth considering how we got here. Why is so much media lost or badly preserved? A recurring reason is that the people in charge are sometimes, but not always, asleep at the wheel. Media is forgotten or stored improperly, and humidity and heat have destroyed more of our history than we will ever know. Sometimes companies handle the material sloppily (I’ve blogged about the use of AI before, but there are countless examples in audio too).

Other times it is a lack of foresight. Have you ever wondered why Dragon Ball Z sounds awful in Japanese? It’s because Toei threw the original audio away after they broadcast it, transferring the original to film but leaving only an inferior optical audio track. It did not sound like that originally. And yet, because multiple people recorded high quality VHS home recordings of DBZ and the fandom tirelessly sourced those tapes and cleaned them up, original broadcast audio of the series exists, albeit in a legal gray zone that Toei can never acknowledge. It is only because of that work that the series can persist in as close to its original form as possible. The best version of Dragon Ball Z, it turns out, is not the one you can buy.

Legality and rights are often the biggest issue. For years until 2022, you couldn't watch Beavis and Butthead without the original music videos (which is the entire point of the show). Likewise Daria used to include licensed music, which has been removed in subsequent releases, and now the only place you can get the original version is through unofficial channels and home recordings. So many things are stuck in a legal limbo, which is often out of the hands of even the creators. Daicon III and IV, the short films that launched Gainax, exist in such a gray zone because they used countless copyrighted characters and music from the Bond movie For Your Eyes Only and the song Twilight by ELO.

And then sometimes there’s just stuff out there that is never legally made available out of laziness or because it’s not worth the effort for big companies. Even before the era of David Zazlav shooting Wile E. Coyote in the head for tax purposes instead of as a funny gag, the number of TV series, TV movies, and stand up specials that never left the vaults of companies like Warner Brothers, HBO and Viacom are countless. The lucky ones got released on Blu-ray or DVD. Some exist in the much more difficult zone of tape and LaserDisc. You can track down some of Martin Short’s Prime Time Glick in solid quality, but not all of it because they only released a best-of DVD and the rest have to be sourced from tape. Did you know there’s a pretty solid John Lithgow/James Garner detective movie called The Glitter Dome? Did you know the creators of House Party made a Twilight Zone-esque black sci-fi anthology movie called Cosmic Slop, starring George Clinton, with a segment based on a story by one of the originators of Critical Race Theory? I do, because neither exists on streaming, and now I own them on tape and LaserDisc respectively. Both of those are good movies, and both were made by HBO. You know what else HBO broadcast? Possibly the greatest magic special ever made, Ricky Jay And His 52 Assistants, directed by David Mamet, which I and others have been trying to track down in better quality for ages.

And even outside of commercially-made art, home videos and live television get lost in time. Commercials that define an era exist only as bad rips or memory unless lovingly preserved. The average person doesn’t know where to begin when it comes to transferring a box of mouldy tapes that have long since outlived the VCR that produced them, family memories sitting in a box to be forgotten until they one day make their way to a dump.

There are countless people attempting to fight the good fight. A lot of them are professionals in boutique distribution and programming, attempting to untangle legal messes, track down tapes and reels, and preserve them in a legal, high-quality form. Some larger companies do great work when it comes to programming and restoration, but often it's smaller companies like Vinegar Syndrome, Discotek Media, and Third Window Films doing the lord’s work. Other times, a government or private grants steps up to preserve essential media. Tokyo Pop, which I reviewed and loved, only got restored because of a company called IndieCollect and money donated by Dolly Parton and Carol Burnett. And then sometimes it’s just someone with a tape deck or a DVD drive who finds something they want to put on YouTube and Archive.org and just does it for the love of the game.

On a certain scale, the space between those groups can be shockingly fluid. A person can start off doing encoding and fansubbing and move into legitimate distribution and preservation. At the end of the day, everyone just wants to save what they love, however they can. As an aggregate they all are trying, but the forces of entropy and capital are so tremendously massive, so impossible to fight, that more often than not it just comes down to a single person deciding one day to make an effort.

I love this tape. Where did I go next?

Part of the problem with preservation, at least when it comes to just analog video, is that it’s been difficult to teach yourself how to do it correctly. I ostensibly have a degree in film and video, and there are intricacies I am still attempting to work out. Much of the knowledge of how to archive and encode video is split between academics, people who work in distribution, several forums like Doom9 and Videohelp, private encoding groups, the knowledge bases of open source software, and talented but depraved anime nerds. All of these different groups have different approaches to the topic. Some are old men perpetually stuck in their ways and workflows, and the forum culture mentality makes a centralized, soup-to-nuts learning experience for analog media difficult, although this has been changing. The lack of clarity on where to start often leads a lot of well-meaning people to take badly ingested footage and do some AI nonsense to it like Topaz and call it a day. Do not do this. While some of these tools are situationally useful, my stance on this sort of thing is clear: Garbage In, Garbage Out.

https://aftermath.site/true-lies-4k-uhd-blu-ray-james-cameron-peter-jackson-park-road-post

The topic of media preservation is so broad as to encompass several articles, but for the purposes of this article I am just going to focus on analog video. (There are people who do their own home scans of 35mm reels, which stems in part from the Original Trilogy forums). When I got the tape of Action Family and FDR: A One Man Show from eBay (also included on the tape was very bad and painfully dated Paul Rodriguez special I Need The Couch), I looked around for someone to capture it, but after a while I decided to just buy a VCR. Surely, capturing it shouldn’t be too hard, right? Wrong. It turns out that if you want to get the highest quality transfer possible, at least according to some people online, it requires a high quality SVHS player, one of several very specific capture cards, and both an internal and external time base corrector. It’s a tried and true method for a lot of people, and a valid route to go down, but none of these devices are produced any more, and the players that do exist break easily, meaning the supply of nice equipment is dwindling because repairing a VCR is a miserable, grueling task and most of the people that learned that are either dead or retired. I was stuck.

That was until I found out about LD-decode and its fork, VHS-decode.

Don’t “transfer,” Decode

When you “transfer” a tape, you are not making an identical copy in the strictest sense. The machine reads the signal on the tape, which is stored as FM RF, and turns that signal into audio and video. If you are digitizing that output, it is then interpreted by your capture card. Any hardware in the analog to digital path has a meaningful impact on the final digital product. The entire signal chain is inherently lossy and subject to the quality of each individual component. There is a more interesting and scientific way to archive analog media that gives better results with far greater control even with consumer hardware: instead of introducing several variables between you and the signal, just cut out the middleman and archive the FM RF signal on the tape. By archiving the FM RF signal, you are making as complete a copy as is possible to work from. You can then use that archive to create workable video, audio, and in some cases extract data and metadata.

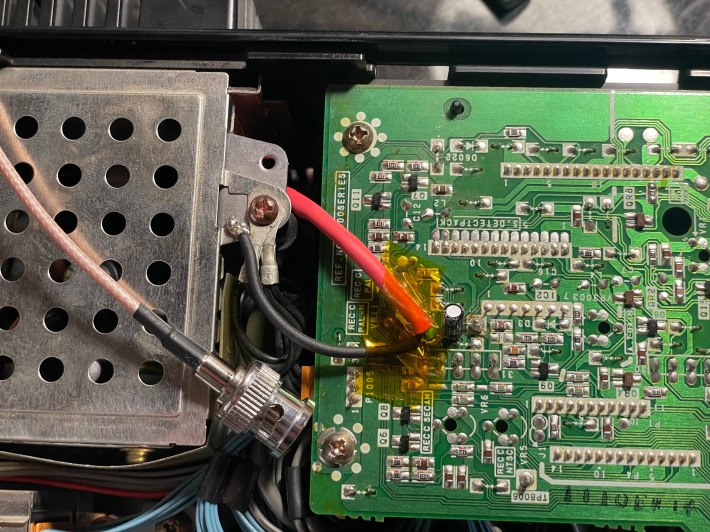

To do this, you’ll need to open up your VHS player, LaserDisc player or camcorder and either connect some cables or do some light soldering.

Before getting into the steps required to do this, a little background on the history of the software and methods behind this process is in order. In the 80s, the BBC commissioned a modern day, computerized version of The Domesday Book, a manuscript of the Grand Survey that was made at the behest of William of Normandy, for its 900th anniversary. This project was called the BBC Domesday Project, and used LaserDiscs in then-new LV-ROM format, which contained both analog video and computer data. Over a million people participated, and the discs included thousands of photos.

"[The BBC Domesday Project was] the first ever crowd sourcing of data," Ian Smallshire told me via Discord, when asked about his motivations for preserving the discs, "with a million school children involved to the mapping and GIS [Geographic information system] side where you can plot heatmaps over aerial photographs and maps. The discs also included thousands of photos along with maps of the UK to enable a Google Maps-style zoom into any location to select regional photos. There is even a Town, Farm and some houses that have a Streetview-style interface 12 years before Google existed."

If you don’t know what a LaserDisc is, it’s a big record sized disc that was the precursor to both CDs and DVDs, but did not achieve the same market penetration as tape and DVD in America. But unlike a DVD, the video on LaserDiscs is analog. It is a strange and wildly important format. Sometimes it contains uncompressed CD-quality audio in addition to the analog audio. Sometimes, it had Dolby Digital. LaserDisc was used for video games like Dragon’s Lair and the LaserActive, and eventually LaserDisc had High Definition as early as 1994 in the form of MUSE (which also has its own branch, MUSE Decode).

“LD [LaserDisc] comes from a totally different era - back in the 80's through mid-90's, it was the only common way to get ~100,000 pictures (albeit in SDTV quality) in an electronically controllable mass-produced way,” ld-decode author Chad Page, who goes by “happycube” online, told me.

The variety of the formats and uses, data and analog, presents a huge issue: How do you make an actual archive of a massively important document like the Domesday Project?

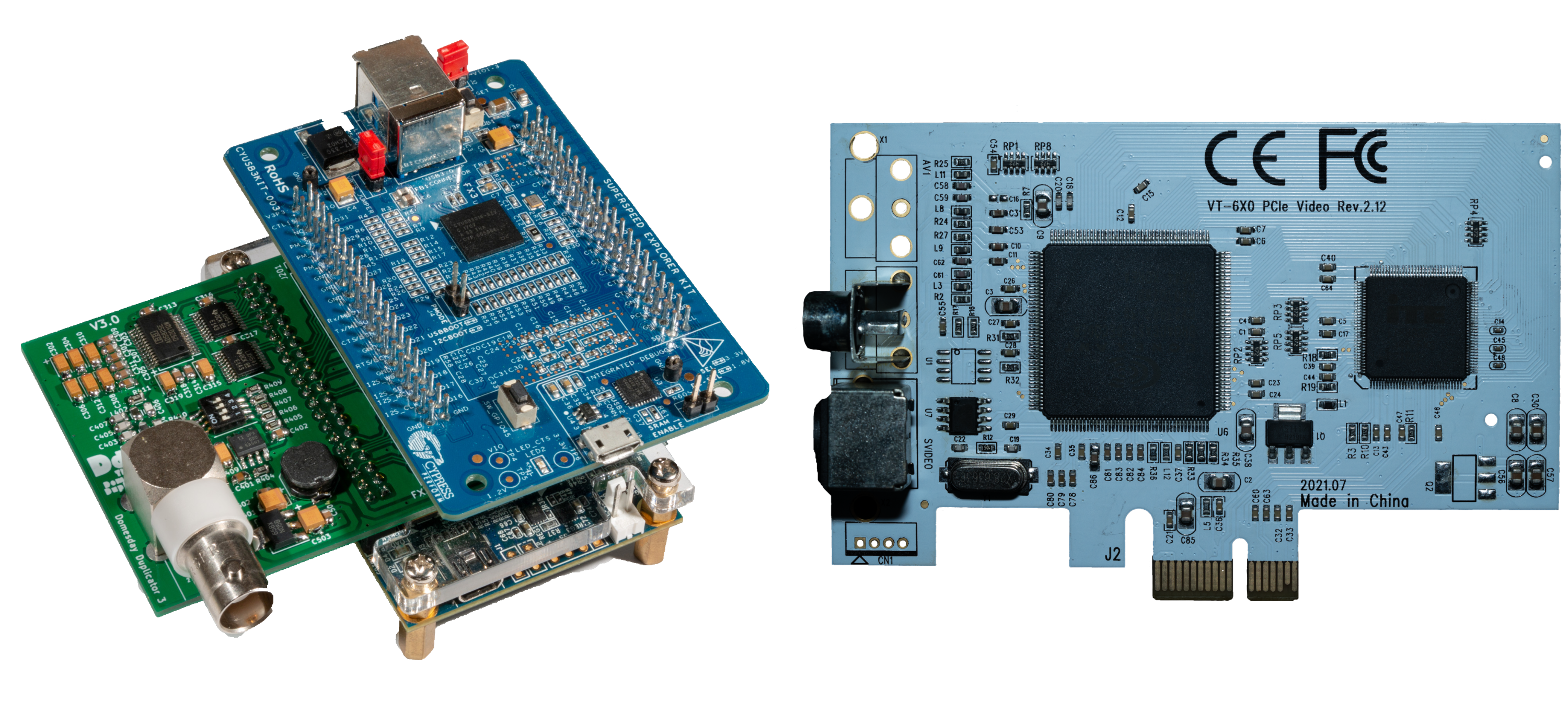

This led to a project called Domesday86 back in 2016 by Simon Inns and Ian Smallshire and the creation of a device called a Domesday Duplicator (DdD for short) by Simon – a custom circuit board sandwiched between two development boards. This device captures the raw RF signal from a LaserDisc player at 40 million samples per second, which has to be modified on a hardware level, a process colloquially called “tapping.” This involves finding the RF point on the device and connecting a BNC cable to that and a ground point. Eventually this merged with Chad’s project, ld-decode, a suite of tools for taking that pure FM RF file and decoding it into a previewable composite signal in a file format .TBC that can be analyzed, tweaked, and adjusted before exporting into the final product.

Eventually ld-decode was extended into a project called VHS-decode by Øyvind Larsen Nygård (who goes by oln online), which applies the same principles to VHS and a variety of other tape formats, although VHS is a different format with its own considerations and complications. Earlier experiments with VHS had happened, but nothing mainline, so Øyvind bought some hardware and decided to build something on top of the existing structure of ld-decode.

"I was interested in finding some better solution for capturing videotapes after being frustrated that there wasn't any proper gear being made for it" he told me over Discord, in contrast to the numerous community hardware projects around upscaling for game consoles "this was the closest thing to someone trying to make something new instead of just relying on 20+ year old hardware."

The project has extended to formats like Betamax, Umatic, Video8, Hi8 and more. The two combined projects have grown tremendously in scope, to the point where you no longer need a Domesday Duplicator at all and can capture any of the formats mentioned using a PCI-E card you buy on Aliexpress (these are called CX cards). New custom hardware is being developed for the project, and while the software was originally developed around Linux, it now runs natively on both Windows and particularly well on Apple’s silicon.

“VHS-decode is particularly interesting because there's so much random content where there's only one copy,” Chad told me. “There's so much more that could and is being lost and there's so much more that could and is being lost more than any one person could realistically - heck, literally watch.”

The process has its hurdles. Because you are archiving the pure FM RF signal, the files are sizable, although traditionally transferred uncompressed video is also fairly big. A single side of a LaserDisc can be upwards of 170 gigabytes when you initially capture it, although this varies depending on capture length and it’s also standard practice to compress that file down more than half the size to a FLAC file. Downsampling is also possible with tape formats. The storage problem will always be an issue, but that’s downwind of much larger issues involving storage. That said, they do make Blu-Rays called M-Discs that are large enough to hold these files (up to 100 Gigabytes) and which are supposed to theoretically last several hundred years. Also, you can get a very reliable recertified 20TB server drive for next to nothing as of this writing, so maybe it’s time to look into a NAS or even just a bunch of drives.

Because you are dealing with raw data, the actual process of decoding itself can be slow, although this will change both new hardware and updates to the project. I have my M2 Macbook Air hooked up to my Domesday Duplicator for both capture and decoding, and it goes along at a decent clip (about 9 FPS for LaserDisc, with faster speeds for downsampled VHS). The process of decoding also involves a little bit of knowledge of how to use the command line, but that’s easily found in the wiki and the community has worked hard on creating automation to lessen the need to do that. Another current limitation is that for VHS and other, similar tape formats, audio and video are captured separately, although contributor Rene Wolf has a mod to synchronize capture across multiple CX cards with provisions for linear audio, and a new piece of hardware called the MISRC being developed as a dual channel successor to the Domesday Duplicator.

That said, there are countless advantages to FM RF decoding. Because you are not reliant on your hardware for decoding and timebase correction, the variation from player to player matters far less. You can get an incredible capture setup with a cheap consumer VCR (I personally prefer Panasonic players), a cable, and an inexpensive card from Aliexpress. What would normally have cost at least a thousand dollars, now instead can be got for less than 100, although I have spent way, way more, albeit with significantly more work.

But the nicest thing about both the community is that they are active and helpful, particularly on Discord. Though there is a lot of information to ingest, the wiki is doggedly maintained by Harry Munday, who also has many other duties including managing workflow and documentation. There is a lot of variation between VHS players, and so installing a tap, testing it, and documenting the process is something that happens on the Discord more often than not. In the process of finding and then soldering a wire to the RF points on my VHS decks, with help and patience from the community, I also contributed photos which now exist on the community wiki.

“Decode is fully open source core code and workflow,” Harry told me over Discord, “with the whole emphasis on community of developers tinkering on each other’s work (insert commie joke) the docs are openly information sourced but, are not open source like a fandom wiki which is the only sane way to keep things in order.”

Once you have both a functioning capture device and a tapped VHS and/or LaserDisc player, you are ready to archive your media. You can then decode that file and look at the resulting file in a previewer called ld-analyse which lets you adjust black and white levels, make tweaks, customize how the image is decoded and isolate potential issues with your capture. From there you can export it in a variety of formats, most of the time an archival interlaced format called FFV1. From there, you encode it into a format that regular people can play, which is where Vapoursynth enters the picture.

Encoding itself is not as simple as installing Handbrake, although that works well enough for a lot of people. It’s a labor-intensive process to get correct, and one of the most fragmented parts of all of this when it comes to documentation, although there are plenty of simple scripts in the decode documents that will work for most people. There’s tons of tools that people use: ffmpeg, Staxrip, VirtualDub2 and avisynth to name a few, but Vapoursynth is the most modern and compatible one that a lot of encoders currently use, in part because it runs on everything. There are some solid yet incomplete guides out there on how to properly use Vapoursynth, outside of the official documentation. I basically use it to load, crop, encode, deinterlace (or remove 3:2 pulldown if it was originally film source), potentially filter my videos, and then run that through an encoder like x264 to get a decently-sized, clean video that most people can watch and store locally. It’s a thankless job, and it’s easy to screw up, but when it’s done great it’s a work of art you don’t notice.

The rabbit hole of endangered media

My interest in this project started with that Chris Elliot screener, but it did not end there. My good friend OK was obsessed with Projections, a series of short music videos from radical queer director Derek Jarman that only was released on VHS in Europe. The tape only cost 50 € and arrived from France smelling of perfume, but the two separate PAL-compatible VCRs that I bought set me back a few hundred dollars (the priciest one broke after a few months). But it exists now on Archive.org because of my actions, in a crisp quality for anyone to see. I did the same with Orson Welles’ movie The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, where Welles pontificates at length and inaccurately on the prophecies of Nostradamus.

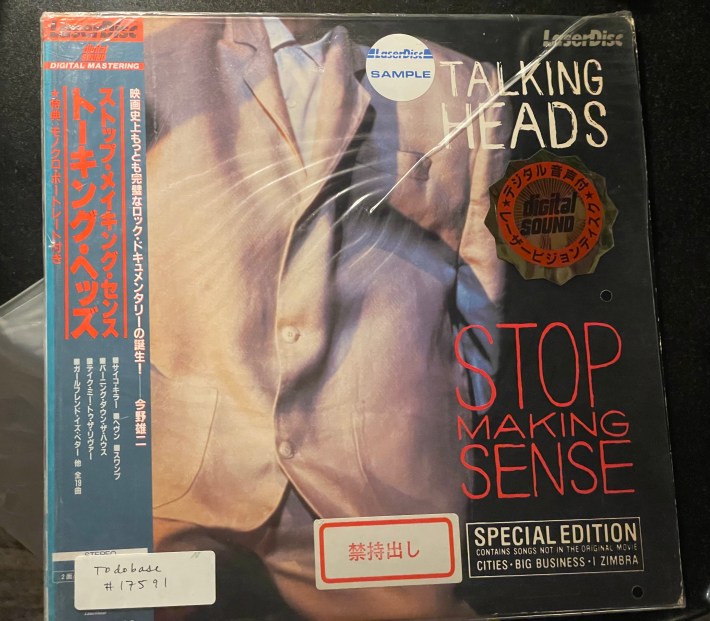

A friend sold me his LaserDisc player, which I modified and started to use to capture movies. I used it to help capture the LaserDisc release of Sweet Home, the Kiyoshi Kurosawa movie and foundation for the Resident Evil franchise. A portion of that disc capture went to a new transfer of the movie by Kineko Video. I also transfer the Japanese laserdisc release of Stop Making Sense, which was included in the recent rerelease of the movie, using David Byrne’s personal copy.

In this process I also helped the folks at the Video Game History Foundation capture a rare tape of lost levels and game art from Sonic The Hedgehog 2. The files now exist online for anyone to look at and decode, both in its raw FM RF state and as a completed video.

I have so many tapes and discs queued up that I’m excited to transfer. Did you know Toei made a disaster film called Prophecies of Nostradamus that got put under self imposed studio ban and has never been released on home video in Japan due to protest from activist groups about its depiction of post-apocalyptic humans? I didn’t until I bought a laserdisc of the weird American dubbed version from a guy who works at Fox News. In the 90’s UCLA did a version of Ernst Lubitch’s One Hour With You, and though that movie has a Blu-ray release, the LaserDisc is the only version with period-accurate yellow and blue color tints used to depict night and interiors. I also transferred Ted Turner’s bizarre colorized version of King Kong for a reader and academic who sent it to me, as well as the original Ninja Turtles cartoons someone sent me (which look atrocious on Paramount+) and now that same person was kind enough to send me the previously mentioned opening animations for Daicon III and IV on Laserdisc, which lead to the foundation of the studio known as Gainax and is debatably one of the first anime OVA in history, depending on how you define it.

I say this not to inflate my own ego but mainly to state that despite my history in video, archiving like this was new territory. My only goal in doing this is to fight as best I can for the art that I love, and to show everyone with the inclination that you too can fight rot and entropy, with both my actions and hopefully with this post.

The path is there for those who choose it

I don’t think everyone needs to be capturing and encoding media. I don’t even think that all media has to be preserved. This is a complicated skill to learn and requires a lot of time, resources and energy to do correctly. But preservation is not just a mechanical act, it's a moral position. It’s about being actively aware of media that isn’t publicly available, and to contribute in some small way, either by supporting small, boutique releases or directly contributing to the transfer of lost media. This only gets better if we help each other, if we exchange notes, and if we make the resources needed to do this kind of archiving as available to every community as possible.

If you’ve never heard of Marion Stokes, I would recommend the documentary about her life Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project. Stokes was a multi-talented woman who, from 1977 until her death in 2012, had up to 8 VCRs meticulously recording television 24/7. She believed that the media had the power to inform and misinform, to warp and lie, and that everyone needed access to complete public archives to seek the truth. Her tireless DIY archiving has yielded one of the most complete singular archives of television in history, a legacy that spans 77,000 VHS and Betamax tapes, an archive that is now, very appropriately, under the protection of The Internet Archive.

Stokes was singular, both as a visionary but also she was literally a single person, someone who chose to do something out of a sense of morality and activism. What she did was in many ways personally unhealthy, and the project took a toll on her life and relationships. But if she had never had both the means or will to do this massive and visionary undertaking, much of our history would be lost forever. Like the Domesday Book, Stokes’ archive has now shaped our understanding of a distinct period in history. The reality is that history is saved and shaped by countless single people. Capital and entropy are arrayed against our collective memory and, barring a massive systemic change, we will continue to live in a corrosive environment for preservation. And as time goes on, and as the last tapes and discs turn to fungus and rot, as the world gets more unstable, the task will get larger and more complex than simply saving tapes.

But until that change comes, if it ever does, think of the media that you love. Of old movies and tapes of live television. Don’t hoard, but simply take stock of where it lives, of its condition; is it accessible? Where? Because if it isn’t, then someone might have to save it, to spend 15 dollars on eBay on an out of print tape or DVD, dig around in an estate sale for live taped television, and unwittingly do everyone else a solid. I have decided that sometimes that person is me, but I am only one person. One day you may come across a YouTube upload that is unbearably poor, or see a listing of something you love more than anything else, a piece of obscure media that deserves far better.

And you too may decide, finally, that that person to save it is you.