I'm sorry, it's been way too long since we ran a Platform blog! So let's make amends by looking at one of the prettiest games of 2024, Wild Bastards, and chatting with the folks responsible for said prettiness.

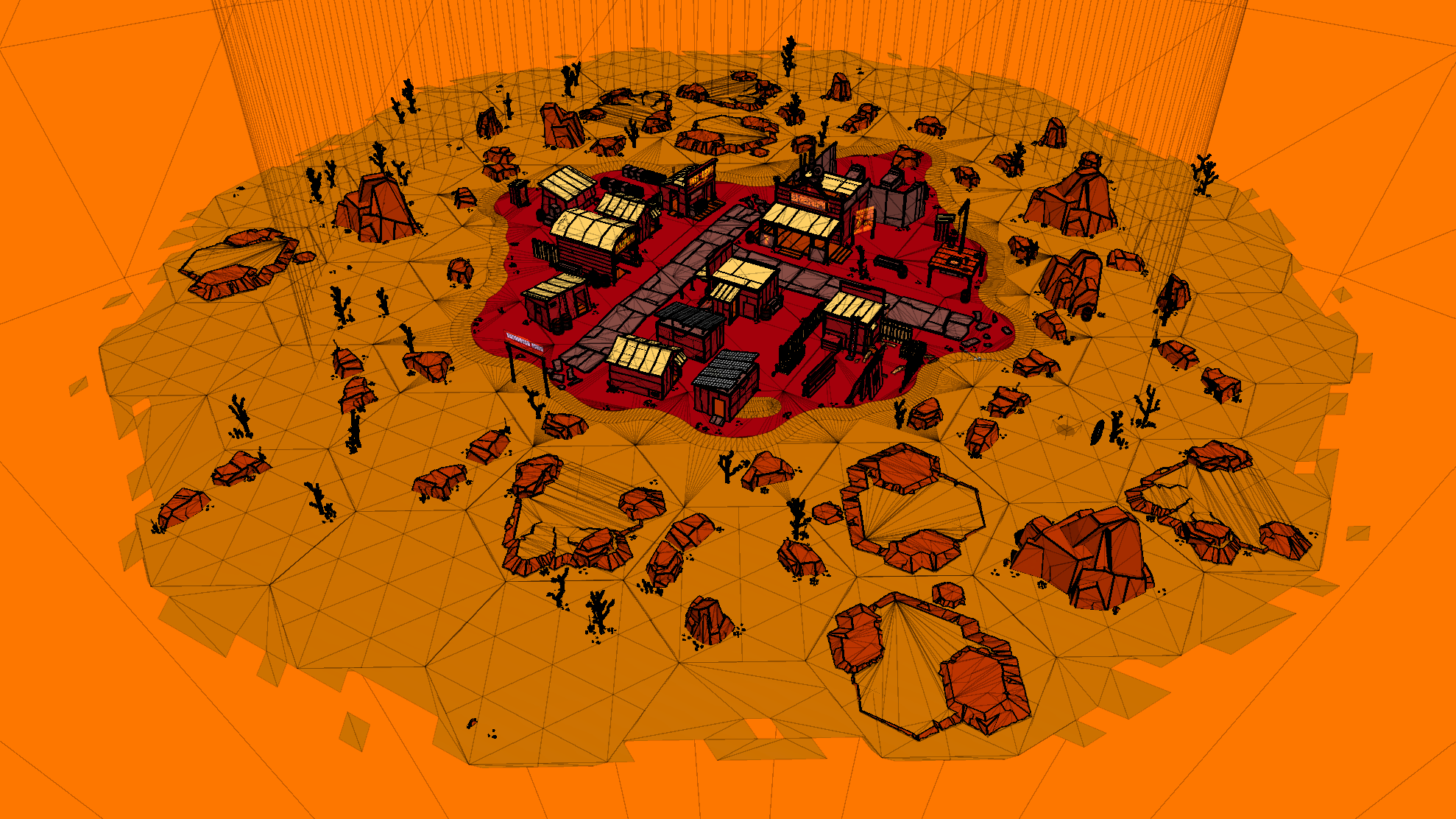

Wild Bastards made my Games Of The Year list for several reasons, but for Platform blog purposes it definitely helped that it was a continuation of developers Blue Manchu's commitment, across 2019's Void Bastards and now this, to an art style that's instantly recognisable for its sharp lines, memorable character designs and bold colours.

To learn more about how the game's visuals came together, I spoke with Blue Manchu's three artists: Ben Lee, Dean Walsh and Irma Walker.

BEN LEE

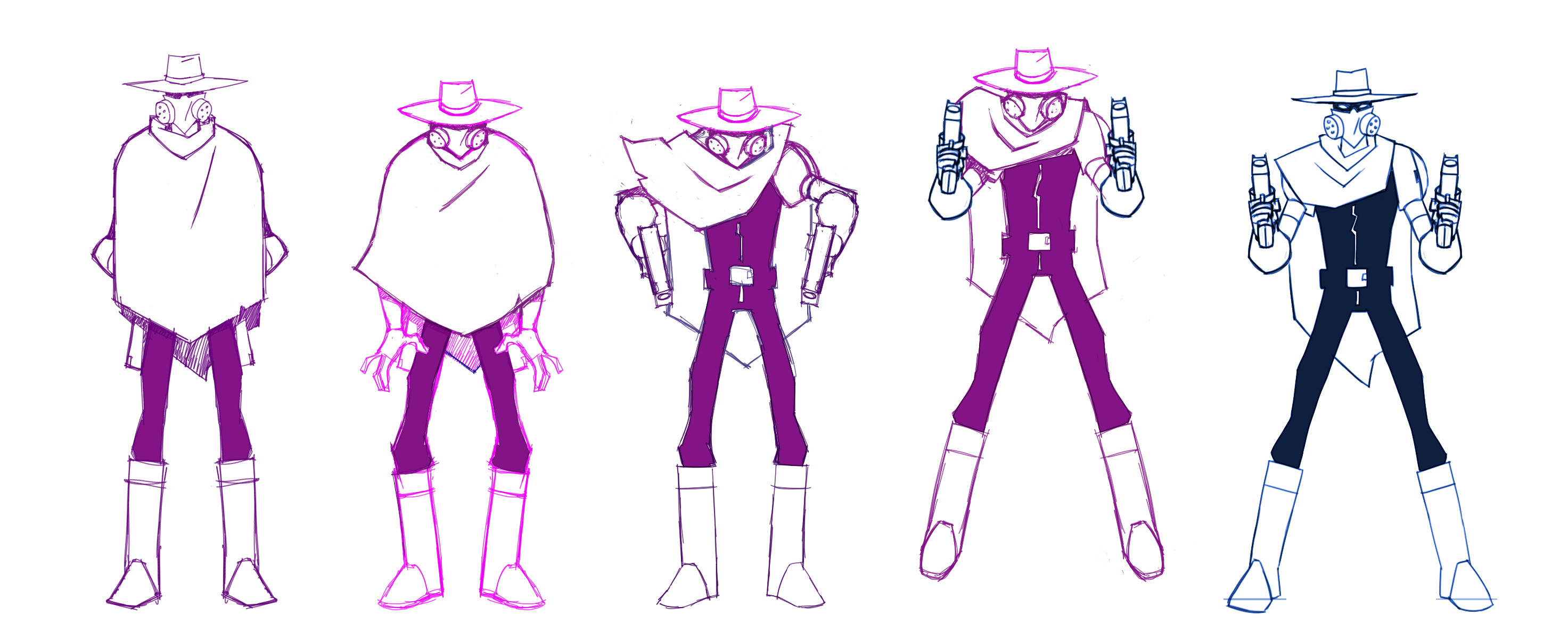

Ben served as Creative Director on the game, but indie dev being indie dev, he was also unofficially everything from art director to concept artist to a 2D illustrator.

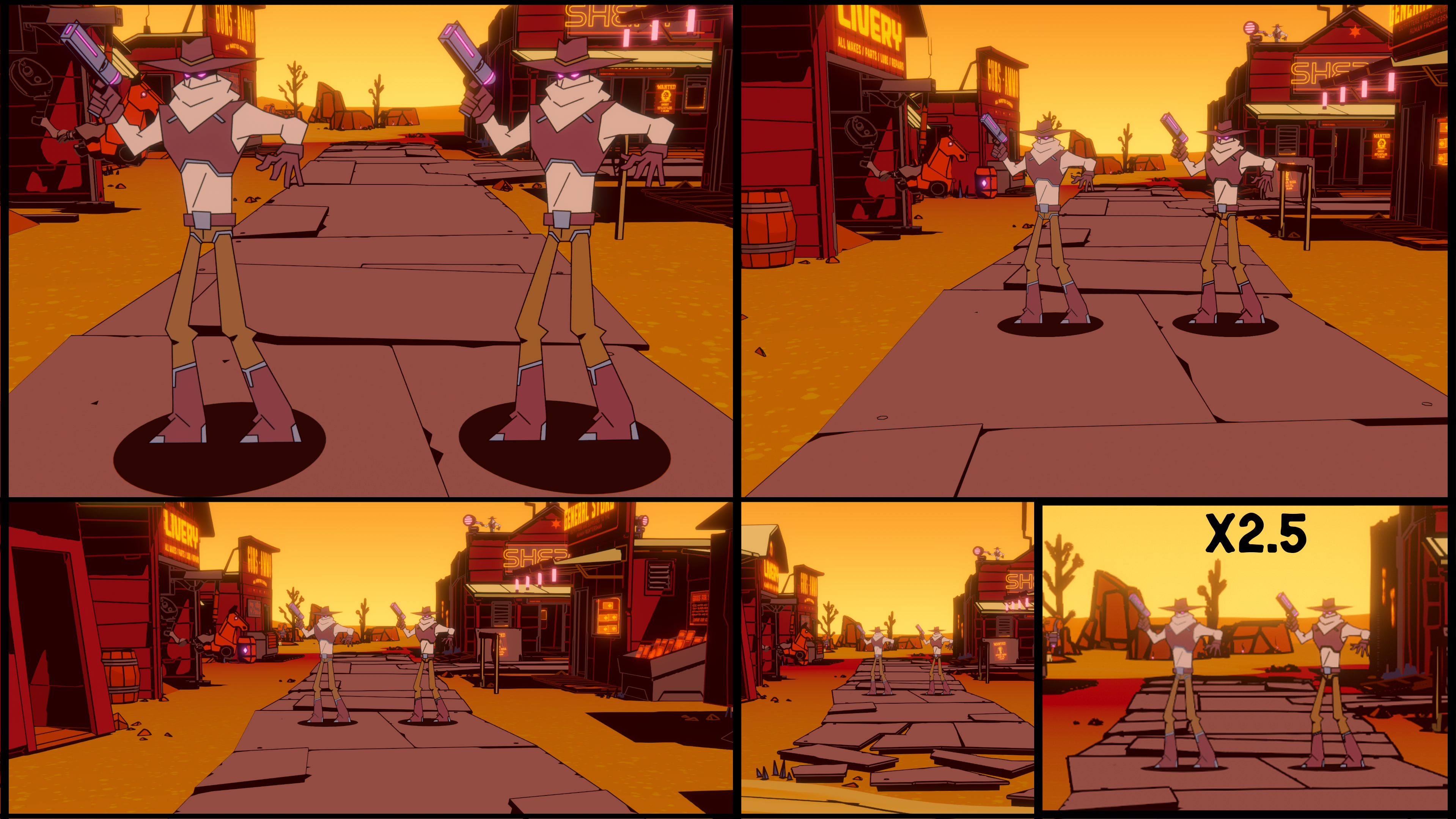

Lee says that, as Creative Director, his chief influences came from about where you'd expect a game that looks like this to have come from. In video game terms, Lucasarts' classic Outlaws--a 90's first-person shooter that employed 2D sprites for its enemies in a 3D space, just like Wild Bastards--was of course a big inspiration, but Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Westerns also played their part.

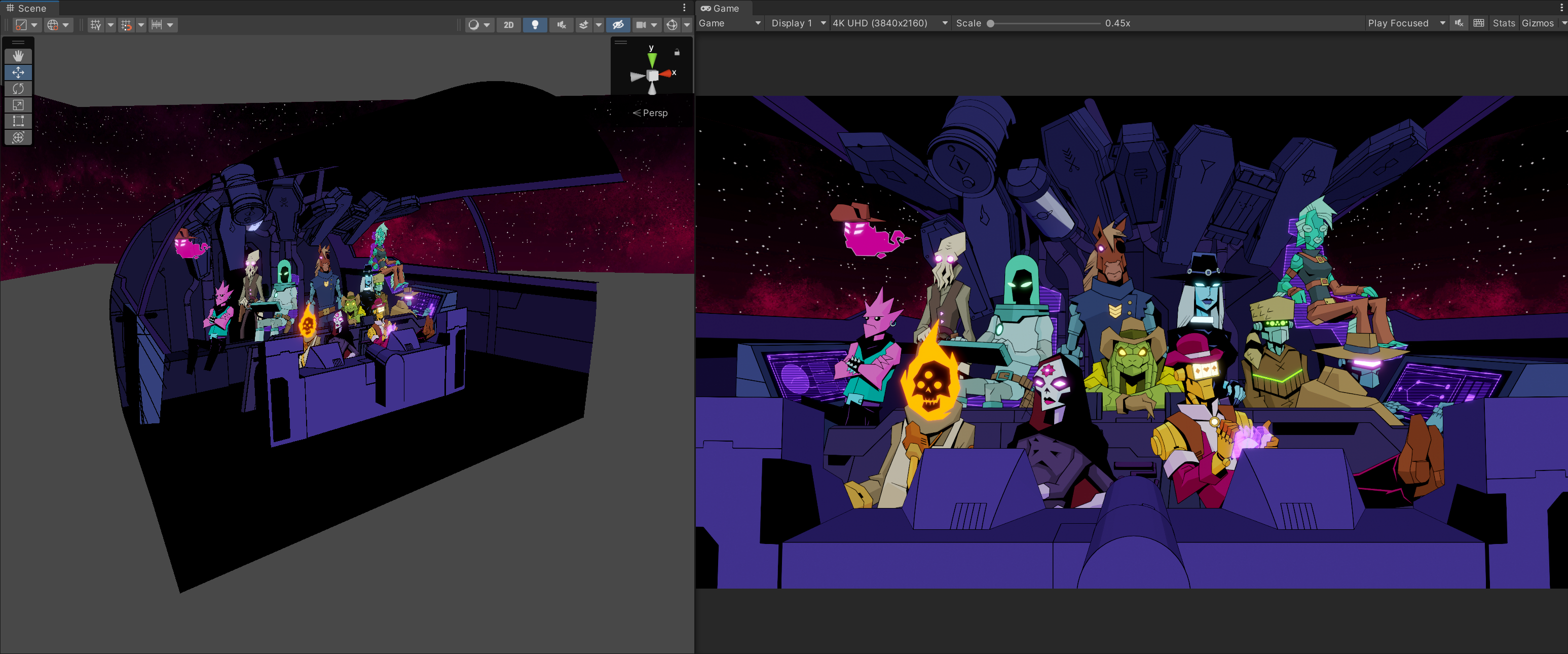

"Void Bastards was very focused around looking like a literal comic page come to life", Lee tells Aftermath. "Wild Bastards moved away from this completely and leant more in a film/animation direction. It's much more widescreen and hyper-saturated looking.

"Given that I design the visuals in our games, and in most cases hand draw them myself, this means that the way I draw kind of naturally ties the games together, even when I don't necessarily want it to."

While Lee both designed and animated the enemies in Void Bastards, this time around the game's increased roster of bad guys meant some of that work was handed off to animation studio Look Mom Productions (part of Blue Ant), a shift that he says gave Wild Bastards its own "unique look".

DEAN WALSH

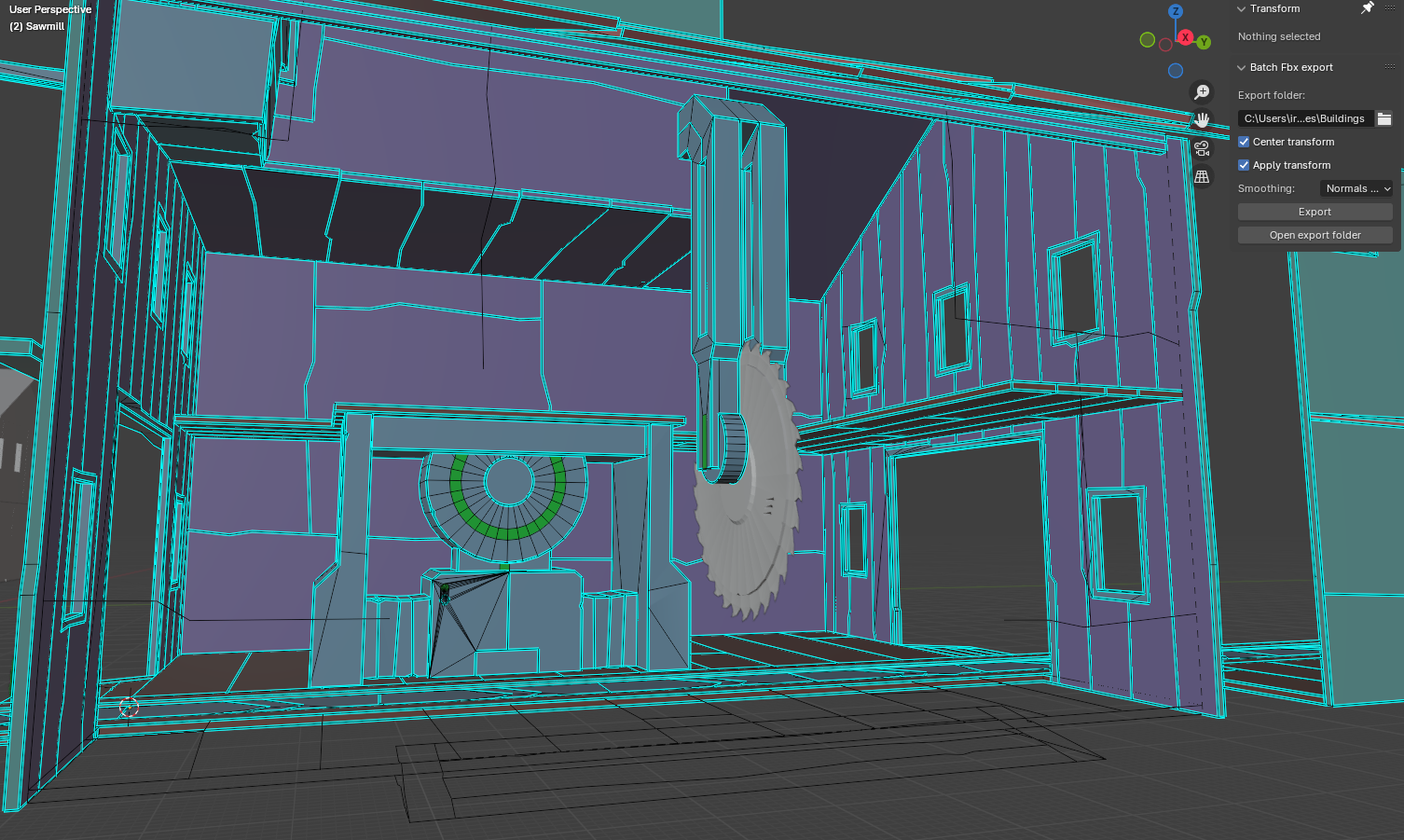

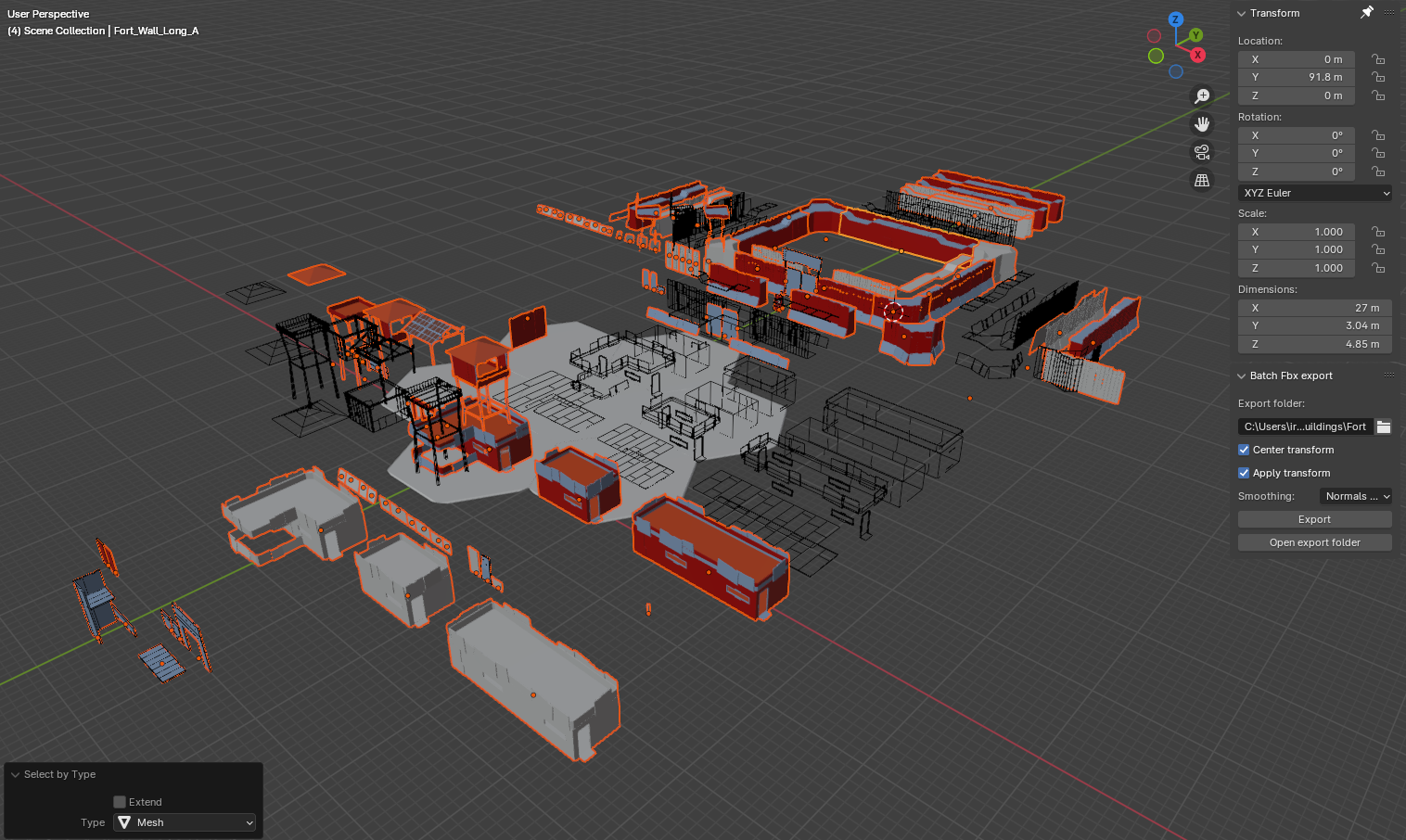

Dean Walsh was 3D Art Lead and Technical Artist on Wild Bastards. "I designed and implemented the asset pipelines for building and importing all the art", he tells Aftermath. "With such a unique game that tends to be a bit more involved; at Blue Manchu we model the 'linework' as geometry rather than as 2D textures applied to the surface of a 3D mesh like you would see with most games. I ended up building most of the shaders too, which define how the light and colour mixes."

Pointing out that both Void Bastards and Wild Bastards have a superficially similar look, I asked if the team has a label or firm structure for it. Nope, turns out it's just...vibes. "I wish we had a term but so far we tend to be describing it more project by project, because, while similar games, they certainly have different approaches."

"Wild Bastards is built around a dynamic sun-based light which also works with our inverted line work, so the lines when shaded swap to colour to give the unique shadow look. Void Bastards was much tighter sight lines, more black and all top-down lit via a dynamic low res light map, I was hand cutting in detail in shadows for that."

I asked Walsh if there was a single piece of work he did for the game that he was most proud of. "The enemy shader uses a second texture that we generate; it does a few things like tell the shader where they glow but also uses a thing called a signed distance field. This is a gradient that can make those lines thicker or thinner based on how far away they are in the level."

"It's a small thing but it keeps enemies from getting softer or less defined, since all the lines in the world do the same thing, so they look as if they are all inked in a comic with the same pen. As a non programmer and very much an artist, being able to fumble the tech to make stuff look the way we want is always a nice surprise."

IRMA WALKER

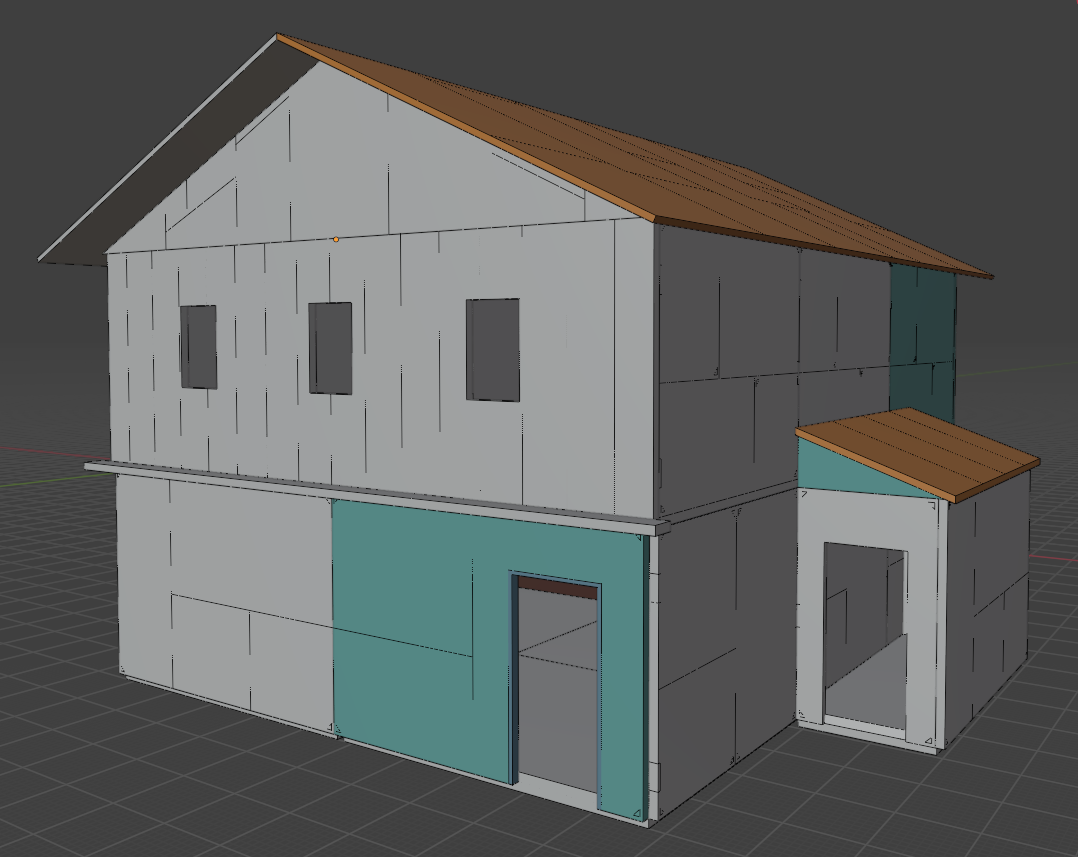

Walker was first brought onto the project to help out on some buildings. "Ultimately these would be deemed too bland to stay as they were", she says, "so as I continued working there my role expanded to creating models based on Ben's concepts and my own ideas, and running passes on the buildings to make them a bit more interesting."

From there, she worked on a bit of everything. "Our roles on the team were usually pretty flexible, we were such a small collection of people that we'd usually end up branching out to handle whatever needed doing; my title was 'Artist' but I would occasionally handle QA and was the go-to for a lot of the fiddly little tasks nobody really wanted to be doing (like checking sprites for tiny errors and hooking them up in-game).”

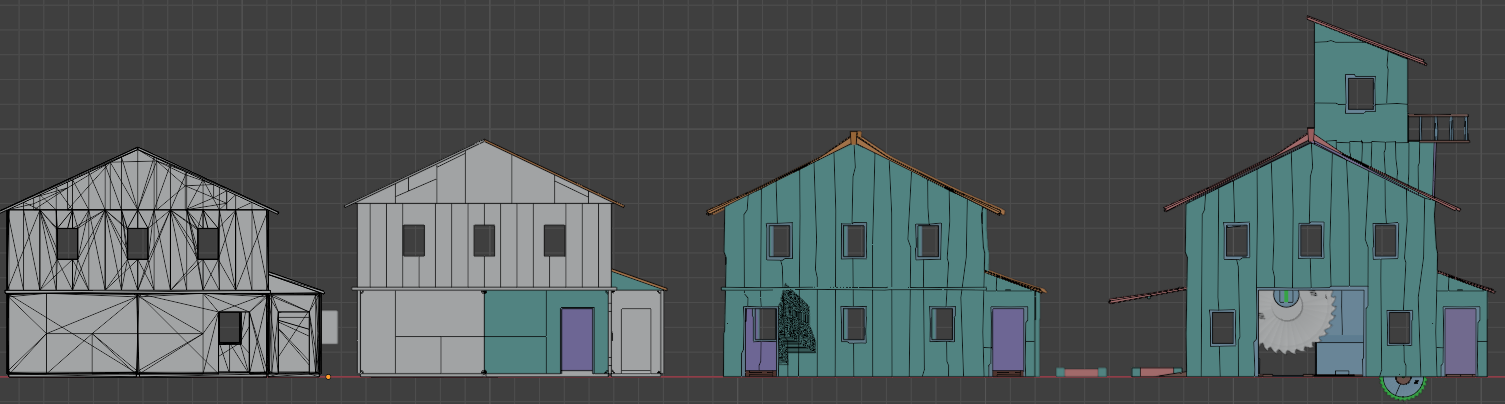

"The sawmill (pictured above, far right) is a really fantastic example of the dedication of our entire team to make the game as visually exciting as it could possibly be. As you can see, the first iteration of our big barn (far left) was not terribly exciting. It definitely did the job of being a big barn, but the details were very uniform, the space not terribly unique to run around in, and the model itself--by the nature of being built of a lot of individual pieces--was a bit haphazard and lacked cohesion."

"Over time we ended up basically re-working every single building and small model in the game. It took time, and added months to the game's production, but I feel like the extra effort was absolutely worth it. The big barn was also used as the base of the Sawmill, which ended up being one of my favourite models I worked on, and really contributed to the really handcrafted, cohesive and visually engaging style we shipped the game with. To me, it all demonstrates the value of iteration. Just because something 'works fine' doesn't mean you shouldn't play around with it; sometimes even small changes can make a drastic difference!"