After 27 years, I have beaten Afterlife.

Many factors contributed to this. One is that there is almost no information on how to play it correctly. Another is that it is one of the most complicated and counter-intuitive and willfully obtuse games I have ever played. It is also wildly funny and structurally fascinating in a way that no other game is. It may be one of my favorite games of all time.

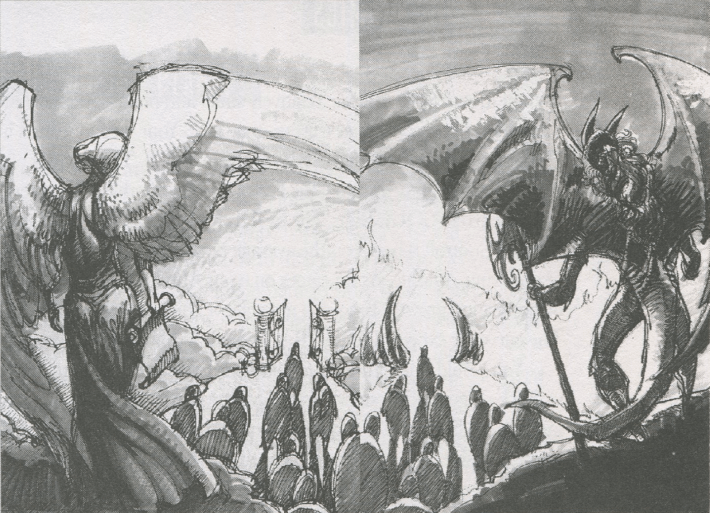

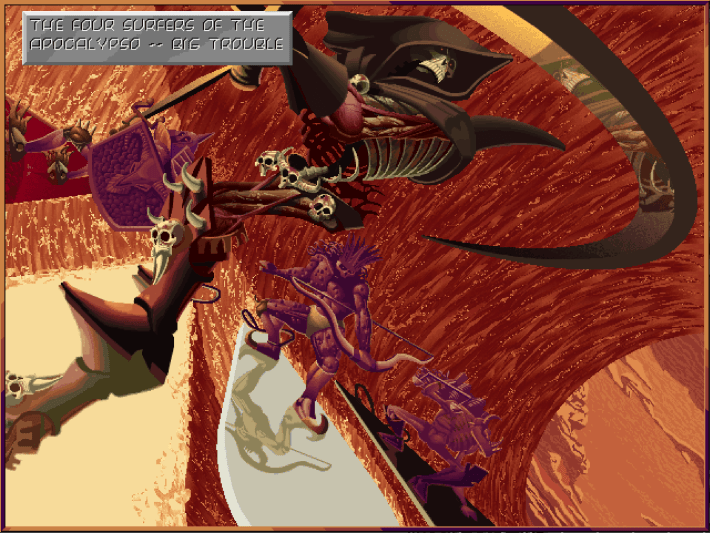

Afterlife came out in 1996, a goofy, satirical riff on the city builder genre generally and Maxis’ SimCity 2000 specifically. The pitch is simple. You are a being in charge of Heaven and Hell for a lone alien planet, which you must manage in tandem, properly zoning your torments and rewards with the assistance of a bubbly Angel named Aria Goodhalo and a dry, sardonic Demon named Jasper Wormwood. If you mess up through one of several lose conditions–like say if you tank your budget–the Powers That Be will take over, and raze your afterlife with the Four Surfers of the Apocalypso, four horsemen minus the horses. Death rides a pale board in this game.

Afterlife was put out by LucasArts in their golden years and has some tremendously funny writing. This usually comes in the writing of your chirpy and dour advisors, and the individual ironic punishments and pleasures put out in Heaven and Hell. Designer Michael Stemmle said he had intended it as Dante’s Inferno version of SimCity, and like Dante, there’s a lotta laughs to be had.

“If you poke around at the writing in Afterlife, you'll find evidence of a number of primary sources,” Michael Stemmle told me over email, citing a vein of Mad Magazine/Weird Al/Wacky Packages style humor, but also pointing to Douglas Adams in particular, as well as Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, and Alan Moore.

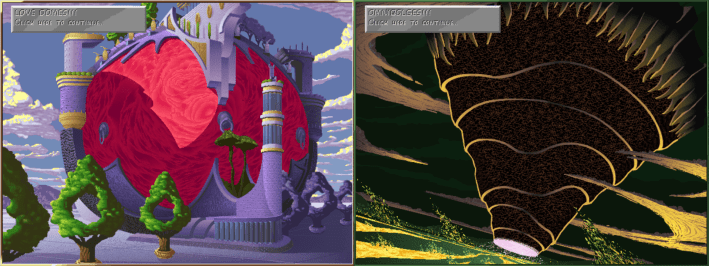

Much of the humor comes from the ironic rewards and torments visited on the residents. Inside every building is a description of what goes on inside. In Heaven, you may visit a reward that is just life as a cat, another that is an eternal childhood afternoon. There is the U.S.O.A, Local #777, a union hall for angels to collectively bargain with the Powers that Be, and The Only Non-Sleazy Singles Bar In Creation, a reward that the game describes as unimaginable “but I gotta figure that they got it figured out in Heaven.” The torments of Hell are equally droll. There’s one called Illuminatiland, which initially appears to be heaven, except the damned are constantly driven to being gaslit into paranoid conspiracy theories. Another, called Tip of Your Tongue, is just a torture of being really close to remembering something forever. And then of course there’s just one eternal torment called Junior High, which is-self explanatory.

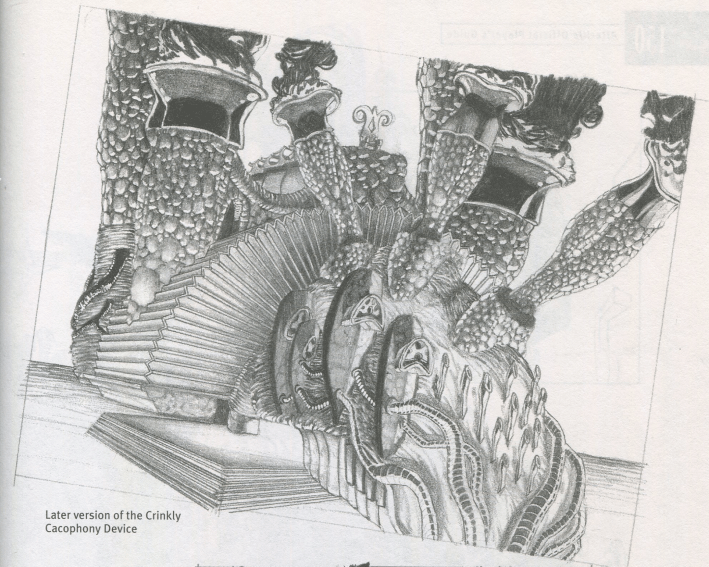

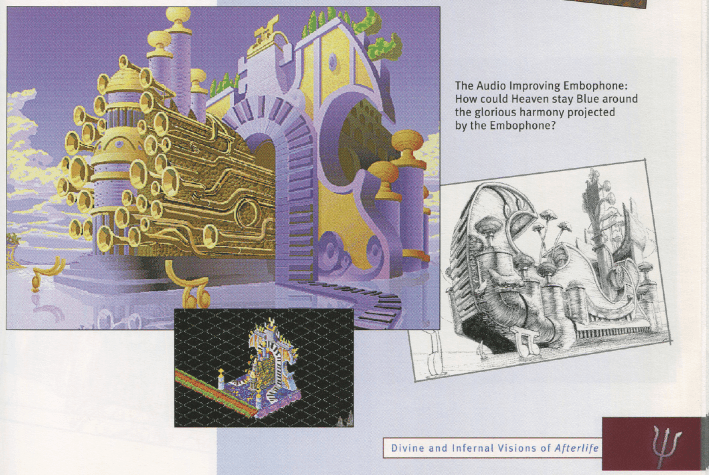

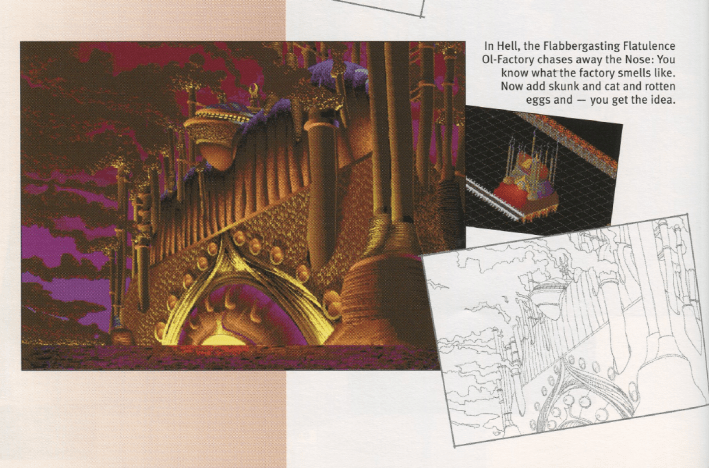

The art style of Afterlife also sets it apart, and not just from every other Lucasarts game. In the very rare strategy guide, Pablo Mica (credited in the game as Paul Mica), said he took influence from H.R. Giger, and described the intended look of Hell as “intestinal.” Along with Bryan Rich and Kevin Evans, they crafted a world that was surreal, funny, distinctly alien, and disgusting to look at, with the closest possible analogue being the Oddworld series, which would kick off the following year.

I have seen Afterlife described as part of the god game genre, and while that tonally feels true, the player is not a god, but a Demiurge. If you are not up to date with Gnostic or Neoplatonic philosophy, a demiurge is (depending on the philosophy) not the omnipotent creator of the world, but merely the being who shapes the physical world. How that shakes out in Afterlife is that you are not all-powerful, and your ass can get fired. You are the regional manager in charge of this one world’s heaven and all its civic infrastructure. This is a city building game, so you better like zoning.

And oh man, is there a lot of zoning. Afterlife is a tremendously funny game both in its jokes and how it plays. It has a lot of what I would call “structural comedy,” but in order to fully understand that, you have to understand how the game works. That’s difficult, because for a while there was only one FAQ that stopped being updated in 1996, and the only evolution in strategy was a lone forum thread from a different guy who couldn’t get in contact with the first guy. The most complete compendium of knowledge was the Afterlife Official Player’s Guide by Jo Ashburn, which is 183 pages long and only got scanned and uploaded to Archive.org last year. I only found out about that guide after beating the game this week.

Unlike SimCity, which zones along commercial, residential and industrial, Afterlife zones along seven deadly sins and seven (modified) heavenly virtues: Envy/Contentment, Avarice/Charity, Gluttony/Temperance, Sloth/Diligence, Pride/Humility, Wrath/Peacefulness and Lust/Chastity. There is also a generic sin and virtue zoning structure, but unlike mixed-use zoning in real life, it is low destroy and wildly inefficient and should not be utilized unless you are very desperate.

The creatures you are in charge of are not humans, but EMBOs (Ethically Mature Biological Organisms) who die and become SOULs (Stuff Of Unending Life). You must create gates, which are prone to overflowing. Power is siphoned from “Ad Infinitum” rocks, which can travel along water and roads, and gates to allow SOULs whose Beliefs account for reincarnation to loop back to the planet. Money is called Pennies from Heaven, which is dictated by the rate of permanent SOULs in your afterlife. (More on this later.)

There is a significant labor component to Afterlife. To run the hereafter, you must either import demons and angels from an adjacent afterlife, or train them in community colleges. Imported and commuting divine beings are your most expensive line item for a while, and if you train too many, the surplus workforce of eternal beings with useless degrees will get restless and cause a mutiny in Heaven and Hell. This can be briefly staunched by creating make-work jobs, but the ideal strategy is to turn off your schools whenever your imported angel and demon rate reaches 20%. One detail the game never tells you is that your colleges have acceptance rates, and that lowering your acceptance rate as much as possible only benefits you since the acceptance rate does not impact your school’s capacity, and increasing the angelic and demonic IQ (AQ and DQ respectively) will cause your fate structures to be more efficient and thus evolve faster. The path to Heaven and Hell is paved with Ivy League snobs.

Like SimCity, you are going to have to contend with natural disasters, which are referred to as “Bad Things.” The Bad Things in this game take the form of interdimensional dad jokes. Early on your cities are harassed by “Bats out of Hell” and “Birds of Paradise” taking a dump on your buildings. “Hell’s Handbasket” and “Heaven’s Nose” will abduct and transplant your buildings. “Disco Inferno” and “Pair of Dice” will wreck your structures with a dancing, “Stayin’ Alive” themed demon and a giant game of Craps. Additionally, typing “SAMNMAX” three times will summon Max from Sam and Max to stomp all over your heaven, and if you abuse the money cheat too many times, you will summon the Death Star.

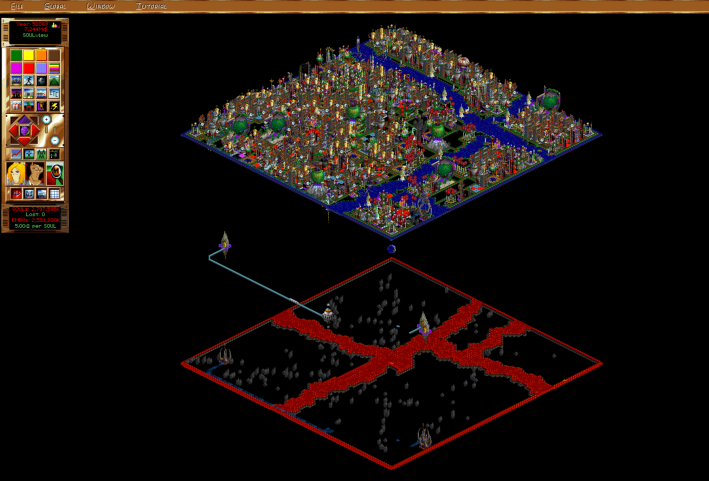

If you played SimCity, much of this seems weird, albeit straightforward, so far. But if you attempt to do what every SimCity player does in every single city ( i.e. “make a city that runs real good”), you will mess up. Heaven is supposed to be efficient, but Hell is not. While the roads in Heaven should be an efficient grid, the roads in Hell should be torture. You want snarled traffic. You want to maximize the space the damned must trudge while being whipped by demons. Compounding that, the residents of Heaven love to mingle, and the residents of Hell should be bored out of their minds, so you should make the layout of Heaven very diverse and efficient, but Hell should be a single long, painful road made of burning pitch and broken glass that is segmented into zones like The Inferno. You want Hell to really suck.

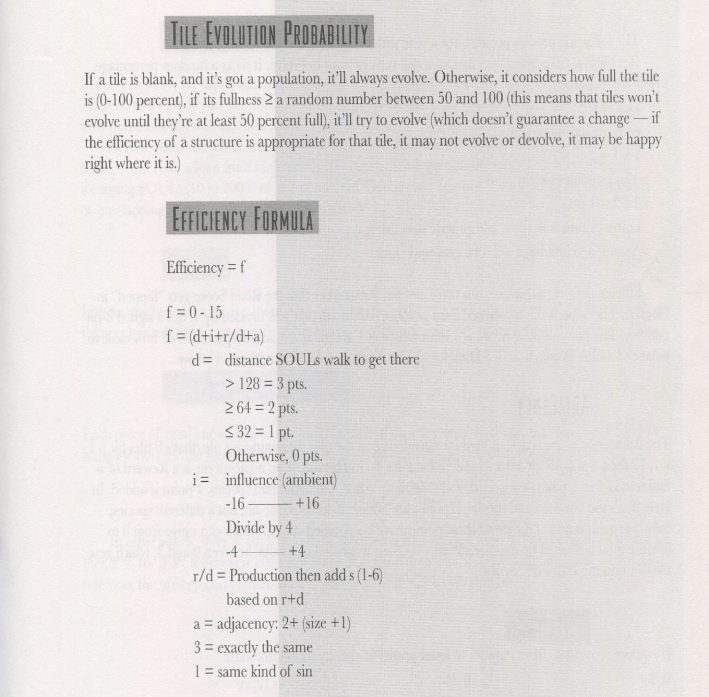

This all impacts the “Vibes” of your afterlife. Vibes are a real thing in this game. Good Vibes are good for Heaven and cause fate structures to evolve, while bad Vibes hamper them. The dynamic is the opposite in Hell. Gates, Siphons and Karma stations put out the wrong Vibes in both planes of existence. The better the Vibes, the more efficient your afterlife will become. This, in turn, dictates your fate structures.

You can also impact Vibes by dropping one of the many, very cool buildings the game gives you called “Gifts” for hitting certain population milestones, like a massive demonic organ that pumps out the worst music imaginable. Schools put down helpful Vibes, and can also drop down a Utopia or Dystopia, which are housing for angels and demons respectively and look sort of like the Bass Pro Shop Pyramid.

A concept that I have always deeply loved in Afterlife is that you get what you believe in. There is no wrong god or wrong belief system; there is only what you think there is. This in turn has a meaningful impact on the population of the EMBOs on your planet. These break down into several opposing categories:

No Afterlife At All/Absolutely Always An Afterlife. Basically atheists and believers. This group has two subcategories:

Heaven And Hell Awais/ Heaven Or Hell Only. HAHAists believe that they will go to Hell first to be punished for sins, while HOHOists believe that they will go to only Heaven or Hell depending on their actions.

Only Cloud Realms Await/ Only Pit Realms Await. These beings believe in either pure reward or damnation no matter their sins or virtues.

Aside from the stance towards damnation, there is the question of reincarnation, which becomes hugely important for how you are running your afterlife.

Souls Undergo Multiple Afterlives/Souls Undergo Singular Afterlifes. SUMAists believe that they will be rewarded for every single sin and virtue, while SUSAists believe that only their most prominent sin or virtue is what they will be punished or rewarded for.

Afterlife Lasts Forever/Reincarnation Always Loops Fate. This dictates if the soul believes in reincarnation.

A HOHOSUSAALFist, for example, would believe exclusively that Heaven or Hell awaits them, that only a single afterlife awaits, and that afterlife lasts forever. This is your classic Christian.

What makes the belief system fascinating is that you have an active role in setting down the belief system on the planet, which in turn impacts how your Heaven functions or makes money. Like a real divine power, you can give your EMBOs a little theological nudge. One of the loss conditions is total thermonuclear warfare, but you can avoid this by downplaying the vice of Wrath and nudging the population towards Peacefulness. Lust and Chastity also have an impact on your population, so boosting Lust will create more souls and vice versa, although Chastity has better vibes in Heaven than Lust does in Hell because horny people are too fun even when they’re ironically tormented for it.

Reincarnation also has a huge impact on the functioning of the economy. Each soul that enters your afterlife generates a specific amount of Pennies From Heaven, and that rate increases with your population. Permanent residents (who do not believe in reincarnation) raise your Soul Rate, while temporary residents that reincarnate do not. However, temporary residents are your wage earners since they generate income every time they enter the gate, while permanent residents only do that once. This means that you ideally need a good mix of both beliefs for an optimal result.

On top of influencing belief systems, you can also impact the technological progress of the planet. Forcibly inspiring thinkers to invent the wheel, irrigation, or industrialization is a cheap way early on to boost the population and cause it to spread over the globe, culminating in the ultimate technology “Advanced Golf”. But inspiration scales as the game goes on, so just like in real life it is the most cost effective to touch the world with the divine hand both technologically and spiritually earlier.

This brings us to a slightly frustrating aspect of playing Afterlife, and that is balance. Balance is very labor intensive, it is never fully explained well, and it is vital to getting anywhere near an endgame. Basically, SOULs are split into permanent and temporary residents. Those residents like different things. Temporary residents prefer physical activities, while permanent ones are into brainy pursuits. Balance is depicted as a black and white, adjustable slider inside every building, which you can adjust. Getting that balance increases the efficiency score of the building, which in turn causes it to evolve and become more dense. The game also gives you the option to auto-balance sins and virtues using a tool called the Macro Manager, but it costs a lot of money, and not hemorrhaging Pennies is crucial early on. I find the act of manually balancing every building strangely soothing, like trimming a bonsai, but maybe I am a masochist who has played this game too much.

The biggest knock against Afterlife is that it is brutally hard to make a profit hereafter. On medium difficulty, you are probably going to be in the red for several thousand years until you go bankrupt. This is how 95% of my games have ended, because I refuse to play on easy.

There are several strategies to prevent this. The first is by far the most effective and funniest: just don’t build Hell for a while. Hell is more expensive to run properly because of the roads, so this cuts your costs down, and the game does not penalize you for not having a Hell. By prioritizing a profitable Heaven first, you make the game easier and give yourself a springboard for doing Hell right.

The secret to beating Afterlife, after much research, is to only build 2x2 structures. This goes against every impulse you may have from playing Sim City 2000. While 3x3 structures are technically more efficient workforce-wise, 2x2 structures have greater overall density, evolve faster, and are easier to work with. You can fit 9 2x2 structures in the same space as 4 3x3 structures, with the 2x2 block accommodating 35.28 million SOULs vs. the 20 million of a maxed out 3x3 block. You can also “lock” structures, so when they achieve their highest peak of evolution, they freeze and don’t backslide. You can also dump all your gift structures on a single area to maximize Vibes, force evolution, then lock and move on.

Another detail the game leaves you to figure out is that certain sins and virtues are just distinctly bad for Heaven or Hell. In Heaven, Chastity, Peace, Humility and Contentment are ideal, while in hell the opposite Sloth, Greed and Gluttony are best. Focus on influencing the planet in these sins and virtues and the evolutionary rate of your structures gets supercharged. What’s funny is that this implies, mechanically, that there are heavenly virtues like Diligence and Charity that just kinda suck to be around, while sins like Lust and Wrath are too much fun.

Like most Sim games there’s really no “beating” the game, but unlocking Love Domes and Omnibolges, the high density structures similar to SimCity 2000’s Arcologies, basically means you’ve won.

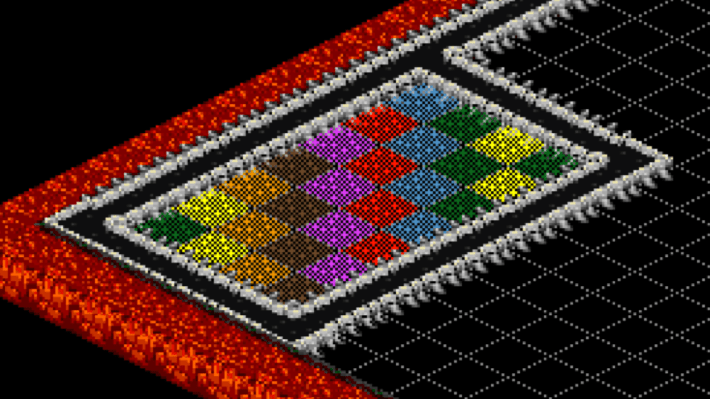

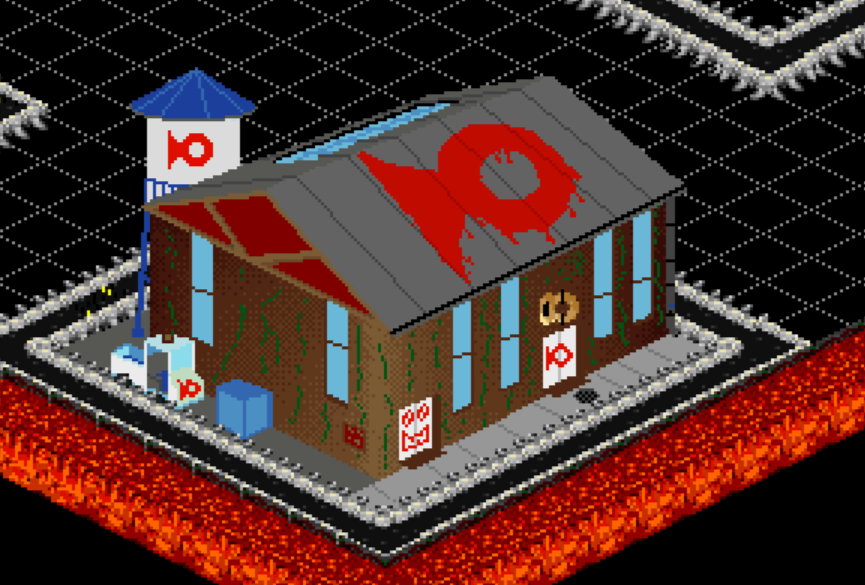

Hidden within Afterlife, there is a secret building you can make. It stores no souls. It has no vibes. To get it you must pause the game, create a 7x7 grid in hell surrounded by roads, in a diagonal rainbow pattern, starting from green to yellow and all the way to blue. When you resume the game the building appears. It’s called The Mother Shak. It’s a crudely rendered warehouse with a logo similar to The Leland Stanford Junior University Marching Band (Stemmle released a shareware adventure game called LSJUMBLE, which features the infamous band). As with many things Mike is responsible for, it is a layer cake of in-jokes.

“It is a spot-on recreation of the heinous structure known as the ‘Band Shak,’ which was the home of the infamous Leland Stanford Junior Marching Band until it was demolished to make way for a far less interesting building in 1998. Unlike the other locations in Afterlife, which were drawn by professional artists, Mother Shak was rendered by yours truly. Probably while drunk and listening to old Who songs. The logo on the building's front door, the horn without a mouthpiece, is colloquially referred to as an ‘Embophone.’ EMBO is an acronym with various meanings within the Stanford Band organization, most of which aren't suitable for public consumption.”

All it contains is an earnest note from Stemmle about what he believed his place in the universe was at the time. In it he states there is more to life than the reality we are subjected to, that we are more than the sum of our DNA, and that there is something immeasurable and immortal to all of us, that goes someplace else and maybe it comes back. The alternative is too horrible to contemplate, and that world where we are all accidents is not one worth living in. He also says that he believes in UFOs, Bigfoot, the resurrection of Christ, and the Loch Ness Monster, so you should take that all with a grain of salt.

I asked Mike if he still felt this way about the universe.

“At the time I built Afterlife, I was not a very religious guy. I clung to the last vestiges of my Roman Catholic upbringing, even though I increasingly found it (and most religions) to be very silly (if not downright dangerous) exercises. Even so, I still held on to the notion that something/one must be responsible for this beautiful universe. I mean, it's too damned cool to have come about by chance, right? So, when scribbling up a note for the Shak, I blurted out the classic bit about finding a watch on a beach, and knowing there had to be a watchmaker out there. I'm sure I thought it was very profound at the time, but the years have made me a mite more rigorous in assessing metaphorical wisdom. These days you'll find me comfortably on Team Atheist - sometimes obnoxiously so.

Is that irony? I hope not. I'm not a big fan.”