Earlier this month, Wonder Woman actress Lynda Carter announced an online fundraiser for the Kamala Harris and Tim Walz campaign called “Geeks and Nerds For Harris.” I stumbled across it earlier this week and felt a mix of intrigue and cringe. It’s part of a movement of identity group-based campaigning for the Democratic candidates, but I wondered how an identity not as clearly linked to the current political landscape as race or gender would make the connection.

Honestly, I figured it would be pretty embarrassing. Some of this is my own deep cynicism: I am not excited about electoral politics, and while I’m thrilled not to be asked to vote for Joe Biden, there’s a lot not to love about Harris. Am I going to vote? Absolutely. Will I celebrate in the streets if the Democrats win, the way I did when Biden won in 2020? Totally–not out of genuine excitement for the candidates, but to share in the relief and joy of four years that will hopefully be less bad, or at least an importantly different kind of bad, than they might otherwise have been. Am I going to wear a Harris/Walz pin, or hang a flag, or give money to their campaign? No.

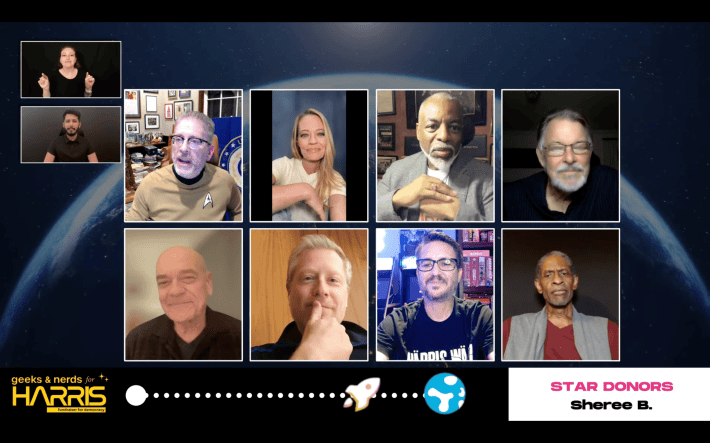

The roughly three-hour “Geeks and Nerds” livestream, which initially involved registration but ultimately moved to YouTube, featured a range of famous guests from sci-fi, fantasy, and superhero media, as well as journalists and politicians. The fundraising aspect was set up as a competition between “Earth Heroes,” for the cast and fans of shows like Supernatural and The Boys, and “Space Explorers,” for folks from and into things like Star Trek, as well as actual astronauts. The competition aspect of the fundraising was mostly contained to occasional donation updates on-stream, and some speakers, such as The Boys and Supernatural casts, matching viewer donations of their team. The idea of competition seemed to work to generate excitement, with the event raising $500,000 dollars for the campaign. Outside of the idea of teams, Wheatus performed “Teenage Dirtbag.” Andy Merrill from The Brak Show and Space Ghost sang a song on a neat-looking ukulele. Bill Nye talked about science. Lynda Carter showed The Boys cast how her old-school Wonder Woman bracelets worked. There was even a post-credits scene.

I was earnestly moved by the excitement in the chat, where many viewers identified themselves as “blue dots” in red states, eager to be in a space with other people who shared both their politics and interests. The viewership topped out at around 25,000 people, who filled the chat with blue hearts, waves, and rainbows. Unlike Harris’ first Twitch stream in August, I didn’t notice any Palestine flags, but the chat was moving intensely quickly. I only noticed one possible troll, with someone promoting Trump in chat toward the end.

In her opening speech, Carter cringingly called Harris a “celestial badass ready to navigate us through the space debris of division” and praised Walz for his “demeanor cooler than a Martian winter,” but after that I was honestly surprised at how serious the event turned out to be. In opening remarks by Representative Robert Garcia, Garcia claimed that “As geeks and nerds, we naturally are progressive people… We meet someone who likes the [Star Wars] Rebel Alliance but they’re voting for Trump. Maybe they don’t understand comics and why social justice and social justice movements have always been a part of our community.” This idea was taken further in a presentation by academics Tanya Cook and Kaela Joseph discussing their book on “fan activism,” which they described as “activism that uses the superpowers of fandom and community to make the world a better place.” They discussed the idea of fandoms as being rooted in enthusiasm and kindness, and called out activism such as charity fundraisers already going on in the fan space. A later presentation including Jacqueline Emerson from The Hunger Games talked about campaigning as an introvert, which while maybe a bit of a stereotype was also pretty useful.

Other segments highlighted the political aspects of certain fandoms. Anthony Rapp from Star Trek: Discovery noted the series’ progressive roots and highlighted queer representation, and Voyager’s Tim Russ highlighted the series’ connection to current labor movements. George Takei called fans rallying to keep the original Star Trek from being cancelled after its second season “activism” and said, “America cannot afford another Trump presidency. So it’s time for our fans to step up again and vote blue up and down the ballot.” I don’t know that I’d call these the same types of “activism,” or that I’d trumpet “voting blue,” but I get what he was going for.

I was prepared for the event to basically The Big Bang Theory-ify politics, but overall I was impressed at how largely elegant and, well, normal the connections were. Besides a few tortured analogies, it mostly focused on helping viewers see how their media of choice had political themes, or how they could leverage their passion and fan practices toward politics. It acknowledged fandoms and fans’ enthusiasm without talking down to them. The word “joy” came up frequently, and though the event lacked the natural relatability and chill of AOC’s Among Us Twitch stream in 2020, it did a mostly good job not pigeon-holing or stereotyping fans or giving fan identities outsized importance on the political stage.

It also stood in sharp comparison to Trump’s outreach via streamers on Kick, with less “notice me, senpai” energy but still keeping the focus on the candidates, and obviously with very different political messages. The Washington Post, writing about news today that the Harris campaign will be advertising on IGN, says “the Trump campaign said Wednesday that the Democratic candidate needs to pay to reach these [gaming] audiences, while enthusiasm for Trump within gaming communities is organic.” I’d argue both parties’ outreach efforts feel forced; both feel like they’re seeking to capitalize on polarized aspects of these scenes. But the narratives of “nerd” media truck in this polarization, and it also reflects the polarization around the political parties in society more broadly. You could argue they’re doing the same thing from opposite ends, though that in no way makes their positions comparable.

It’s interesting to me that both parties see gamers, nerds, and geeks as a voting bloc worth courting. Carter told Deadline prior to the event, “The way I feel about it is that we are bringing in people whose voices have not been heard in this [campaign] at least it feels like anyway, they haven’t been heard in this way.” But beyond the “Geeks and Nerds” viewers who identified themselves as political minorities in their home states, what makes them a political identity that hasn’t been heard in the campaign? Do geeks and nerds have specific political needs? I’m inherently suspicious of the idea of “geek,” or for that matter “gamer,” as an identity marker; in my experience, I’ve mostly seen it wielded in the negative, used to justify harassment or patrol the borders of an interest. There’s value in taking that back, and highlighting the liberal or progressive themes in media as a contrast to those who would claim the opposite, as well as helping people see how the things they appreciate in their media have corollaries in the real world. But politicizing an identity doesn’t make it a political one.

I’m also leery of claiming a fandom as an identity because I worry it pegs people’s power and energy to something outside themselves, to work that may be made by artists who share similarities with their fans but is ultimately owned and controlled by corporations and their money. It’s the same suspicion I bring to conversations about queer and trans representation in Disney or children’s TV or video games: that it can lead to a certain waiting for recognition from a system that my own politics–rooted in the radical queer and trans movements of a more confrontational, less accepting time–say can never fully be trusted. I won’t deny the value of seeing yourself in Doctor Who or Star Trek (I say this as someone with a Doctor Who tattoo), but these will never take the place, to me, of work made without the intermediary of the predominantly cis and straight people who ultimately pull the strings. By identifying people as “fans,” and then leveraging that fandom into being a “fan” for Harris/Walz, this framing runs the risk of just funnelling power upward. We’ve seen Trump leverage this for his own ends; surely the Harris campaign wants to do the same.

But this is also how electoral politics work. The presenters in “Geeks and Nerds for Harris” whipping up the world-changing power and importance of their candidates are, at its core, giving away their power to someone else, someone who will never actually, fully have their best interests at heart. Perhaps the event’s audience is already inherently primed for such a transfer through the nature of fandom, in ways that aren’t necessarily positive. At the same time, this focus doesn’t stop people from getting more directly involved in politics, and could also be a good way to inspire people into more hands-on local action. My own political beliefs have shifted enough over the years to recognize that, however much electoral politics go against the ways I think the world should be structured, they are a space where a hugely consequential battle is currently being fought. The money and energies of our politics, however they overlap with the energies of our other interests, are not best used in service of people running for president, but that doesn’t mean I should pretend all that doesn’t exist.

Maybe the event’s main value, beyond raising money for the campaign that it will hopefully use in battleground states, lay in making space for people in the chat to be together, especially those who feel isolated. That’s something fandom has always been good at, though that’s been used for both positive and negative ends. Creating a campaign event that felt fun and positive has value, as does any kind of pushback to the hateful and conservative narratives running rampant in “nerd” spaces, even if the nature of the event means it was preaching to the choir. If “Geeks and Nerds for Harris” served as a place for people to feel energetic and empowered about getting involved, and as a stepping stone for other ways they can effect change in addition to voting, that’s ultimately a good thing.