Imagine the opening credits playing on a pilot episode of a television show—the scene-setting, the character introductions teasing backstories and defining traits, the tantalizing hints of the larger story ahead. That’s what one-shots do for manga: These special chapters, typically longer than the standard 20-page weekly installments, offer readers their first glimpse into a series’ expansive universe.

Some one-shots, like Look Back by Tatsuki Fujimoto, the creator of Chainsaw Man, exist as standalone masterpieces, perfectly self-contained. Others, like those for shonen the big three—One Piece, Naruto and Bleach— act as the seeds from which global phenomena grew. One-shots are mangaka’s hail mary—a chance to go from a complete unknown to a household name in the manga world. While the journey from one-shot to full-fledged manga series isn’t foolproof, Rafał Jaki from No\Name told me the story behind the grand opening and grand closing of Shueisha’s first Western-published manga series.

No\Name in a nutshell

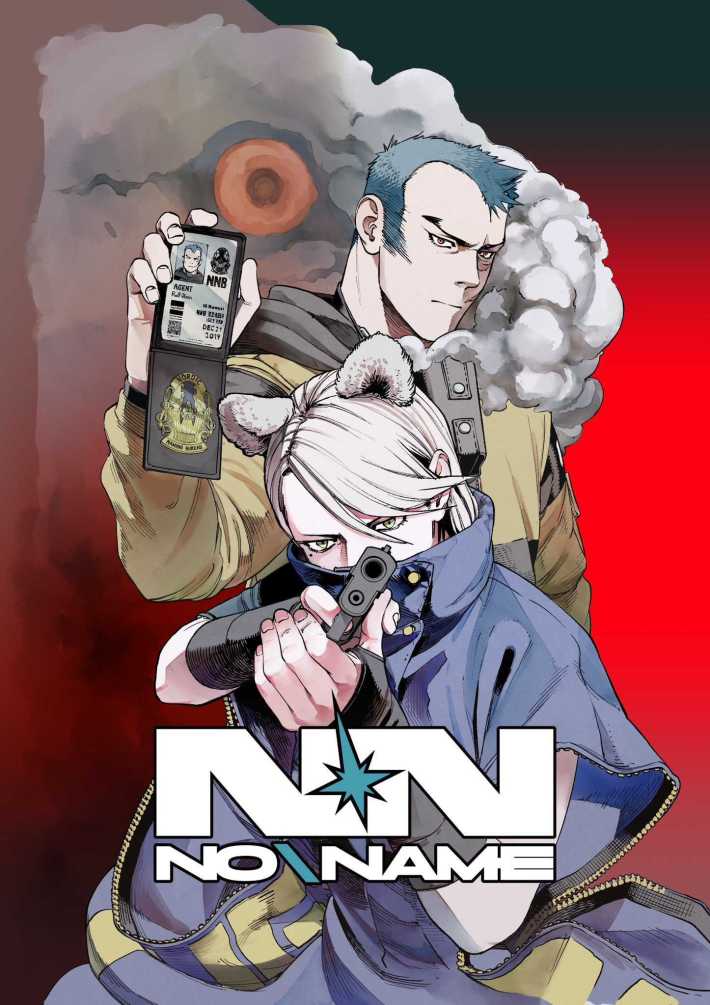

When manga fans discovered that Cyberpunk: Edgerunners showrunner Rafał Jaki had taken a creative leap post-anime and won Shueisha’s Shonen Jump+ Creators competition, excitement reached a fever pitch. His imaginative new series, No\Name, made history as the first Western manga to be published bi-weekly alongside fan-favorite titles like Dandadan.

No\Name, a dark mystery thriller by Jaki and artist MACHINE GAMU, is set in Northern Europe. The series poses an intriguing question: What if your name endowed you with supernatural powers tied to its meaning? Central to this world is the Nordic Naming Bureau (NNB), a government organization that issues names to newborns, effectively regulating both their powers and their societal standing.

The story follows two NNA agents—Ralf, whose name translates to “wolf commander,” and Ursula, meaning “bear”—as they investigate the disappearance of a prominent public figure’s child. What unfolds is a tense and action-packed mystery, exploring the many layers of the series’ unique premise. Within a week of its one-shot chapter release in September 2023, No\Name captivated over one million readers, and their enthusiastic response paved the way for the series to be officially picked up for publication in July of the following year. However, after an intense 14-chapter run, the series came to an abrupt end, leaving manga readers to play armchair expert—as they’re often left to do—wondering if No\Name was the latest in a promising new shonen series cancelled before things got going.

To clear up the confusion, I spoke with Jaki to discuss his experience publishing on Shonen Jump+ and to debunk misconceptions about what the workflow was like for a creator working with one of the world’s most renowned publishers.

Contrary to popular belief, No\Name wasn’t axed

Jaki clarified that No\Name was neither axed nor cancelled prematurely, despite online speculation. While Jaki acknowledged that the series' ending mirrored what typically happens when a manga is cancelled, he emphasized that the conclusion was in line with the editorial agreement Shueisha had outlined for him before the series even began its publication.

“First, they wanted to see more finished chapters to review them and see our ability to continue and execute, but also, they asked for the first arc of the story,” Jaki said. “I’m a ‘discovery’ writer, which means that I tend to do my best work while I’m writing the actual script vs having a detailed outline (so the plan of events and stakes and characters involved) as a starting point. But they needed to see an outline, which requires a pretty detailed plan (meaning scene by scene, chapter by chapter). To do that, we needed to settle on a page count that resulted in a number of volumes that Jump+ is committing to publishing physically in Japan.”

At first, Jaki envisioned No\Name as a concise series spanning four to five volumes with 30-page chapters, which he believed would “do the trick” to cover its full run. However, Shueisha had a different perspective. Considering that Jaki and GAMU were a “rookie team,” the publisher felt that Jaki’s original plan would be “too much as a binding commitment.” As a result, the strategy was adjusted — No\Name’s first two arcs would unfold over two volumes, culminating in “a proper, satisfying ending.”

“We of course asked if we could continue past two volumes, and they said that it is a possibility only if it becomes a hit. So we went to work hoping it will become one and gave our best. The reality was that it was popular in the West (but not a top hit) and doing barely ok in Japan, so they kept their word, and we ended it according to the outline we provided before we even started the serialization,” Jaki said.

“The really cool and surprising twist at the end was that the editorial team (on their own) put this message at the last page of the final chapter, so it gave us confidence to get to work on a new thing,” Jaki added, referencing No\Name’s afterword thanking readers for following the series and asking them to look forward to the creators’ next work.

“Buffer” chapters in manga production

While corresponding for my prior feature interview with Jaki, he’d mentioned he had chapters prepared weeks before their release. The practice was news to me. Years of writing articles about how mangaka like Hunter x Hunter’s Yoshihiro Togashi put his series on hiatus after falling ill trying to meet grueling production demands and Fujimoto wishing he could stop drawing Chainsaw Man and write its story to meet weekly releases made Jaki’s casual revelation sound like a no-brainer solution to cushion creative burnout plaguing the industry. Although Jaki couldn’t speak on the production schedule for other mangaka, he said that other mangaka tend to have “quite a few ‘buffer’ chapters” ready to go before they start serialization on a weekly or bi-weekly series.

“In print, Weekly Shonen Jump the chapters are around 20 pages usually, and that goes out every week. On the Jump+ and Manga+ app you have also bi-weekly serialization (No\Name being one of them). To hit that WSJ weekly release, a mangaka will have assistants working on backgrounds, VFX, SFX etc. For example, Fujimoto assistants were in the past: Tatsuya Endo (Spy X Family), Oto Tōda (Chihayafuru), Yuji Kaku (Hell’s Paradise), Yukinobu Tatsu (Dandadan), and Tohru Kuramori (Centuria),” Jaki said. “So, a company of highly skilled people under one mangaka works as a team to hit that deadline. Of course, this does not mean that all mangaka that are serialized in WSJ get to have this amount of stuff to do it - but once you get the initial sales numbers, it makes sense to have that setup. However, multiple chapters are prepared in advance before a series starts.”

He continued: “It’s more common to prepare more chapters independently without any assistants for bi-weekly. We had volume 1 done for No\Name before we started, but we did not have any assistant working with GAMU on the art, so it would take him 3-4 weeks to complete a chapter, and that meant we had just enough time to make our deadlines for volume 2. But as life happens–someone will get sick and you lose a week or so, we had a computer die on GAMU and we lost some work and a few days to buy and set up a new one, etc.–and that buffer gets eaten up. GAMU did work each day all day to hit the deadlines we had, but if we would continue past volume two, we would have to hire an assistant to be able to deliver the chapter bi-weekly, and you need to be a hit for it to make financial sense.”

Combine that with the challenges already faced by Western manga letterers and translators, who often juggle multiple series just to make ends meet, No\Name’s continuation would’ve added another layer of complexity in its production, requiring localizers and typographers to rework the series for Japanese audiences based on Jaki and GAMU’s original efforts—all while racing to meet the demanding schedule of a bi-weekly publication. While some manga series have managed to secure continuation thanks to the collective efforts of overseas fans boosting Japanese volume sales, despite Jaki’s best social media efforts, No\Name didn’t follow the same trajectory.

Manga volume sales (in Japan) make or break a series

As Jaki noted in a post on his official Twitter account, No\Name was performing strongly when it launched on Jump+ in Japan and Manga+ in the West with around 900,000 readers in Japan and 250,000 in the West. However, the series faced a sharp decline in readers, losing more readers than other new shonen series like MAD in Japan from chapter two onward, making a continuation unlikely unless volume one of the series sold well in Japan.

“After we started serialization, we got numbers from the Japanese app and web views, which were on the edge. They could go either way, so the next threshold was the physical volume one sales in Japan that could change the already-established plan to finish with two volumes,” Jaki said.

Being able to see how things were going under the hood with weekly reader metrics and volume sales, Jaki and GAMU had an inclination that the series wouldn’t outlive their initial agreement.

“We lived in a different head space vs our editor — he was thinking that if volume one physical Japanese sales [were] robust, we can talk about doing more than two volumes, where we were hoping that it would happen and wanted to do everything we could to help that,” Jaki said. “So our editor told us after the initial sales number of volume one came in that, as planned, the series will end with volume two.”

From a reader's perspective, No\Name had been steadily building momentum, expanding its overarching mystery far beyond the groundwork laid in its earlier chapters. So when it was announced that the manga’s 14th chapter would serve as its finale, fans were left reeling. Ralf and Ursula were on the brink of uncovering the mastermind behind a newly introduced government conspiracy that involved abducting unnamed children from foreign countries and only had 20 pages to wrap everything up.

In February 2025, the series’ final chapter took a sharp turn, culminating in a meta ending where the protagonists parted ways with the hope of reuniting in the future. This left readers wondering whether Jaki and GAMU had to adjust the trajectory of No\Name to tie up loose plot threads in its final chapter. Jaki confirmed that they did have to make changes and leave certain story developments on the cutting room floor during the collaboration process. However, despite these adjustments, the series concluded on the note they had initially envisioned when pitching the story prior to serialization.

“As a ‘discovery writer’ working under a strict outline (that I had to write before writing the scripts), we knew where we were heading. However, I still changed a bunch of stuff, removing possible hints and threads I knew I could not finish at this point,” Jaki said. “Still, overall, we did not change anything significant from the outline I submitted before we started serialization.”

No hard feelings

Manga publishers like Shueisha are known for frequently greenlighting new series, but just as often, they pull the plug on others. Endings can sometimes feel abrupt, offering little insight into the directions the story might have taken. In some cases, such as Yuki Kawaguchi’s The Hunter’s Guild: Red Hood’s sudden end, conclusions delve into meta-textual territory, engaging readers in a dialogue about the reality of manga cancellations.

Reflecting on No\Name, Jaki remains content with how the series wrapped up. While he acknowledges there were additional avenues he would have loved to explore in terms of its world-building and characters, he’s satisfied with the outcome.

“My biggest takeaway is that even though I’ve been a manga fan for as long as I can remember, clarity of the story and art is key, and characters need to spell out their purpose in the story early and frequently,” Jaki said. “Japanese readers especially put a lot of emphasis on this vs the West, where ‘innovation’ or finding a new and fresh thing is priced at a premium.”

From his early days as a devoted manga fan, Jaki’s journey with No\Name spans 24 years, rooted in the formative experiences of a 13-year-old Polish kid captivated by Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball. That passion ultimately propelled him to the milestone of becoming Shonen Jump+’s first Western manga creator. As our conversation drew to a close, the lingering question I had for Jaki was whether working on his series — and getting a firsthand look at the industry’s inner workings — had ever left him feeling disillusioned.

“My background is the business and publishing side of the video game industry, so I was not surprised at all. In general, American comics, board games, manga, film, and TV work similarly – everyone wants to make the next big thing, and the system is tailored towards that. Because I know a lot about how things are monetized, I understood that the likelihood of us becoming the next big thing on the first try is unlikely at best,” Jaki said. “ As a creator I must believe that what we are doing is worthy of people’s time and attention – so I would struggle not to get my hopes up, but at the same time have faith in what we are doing as it would be very easy to be overwhelmed by how big of a challenge this all is.”

He continued, “At the end of the day, we did a thing, some people liked it a lot (but not the needed amount to make more), and we learned and can go and try to make a new thing with all the lessons we have in our pocket.”

As far as what the future holds, Jaki can’t say much about what he and GAMU are cooking, but they are currently working on two concepts together. One, he hopes, “can go further :).”

Inside Baseball Week is our annual week of stories about the lesser-known parts of game development, the ins and outs of games journalism, and a peek behind the curtain at Aftermath. It's part of our second, even more ambitious subscription drive, which you can learn more about here. If you like what you see, please consider subscribing!