When you think of Sanrio, you think of Hello Kitty; you don’t think of movies. But from 1977 to 1986, at the behest of founder and president Shintaro Tsuji, Sanrio had a bizarre run of films it produced, financed, or distributed in America and Japan, many of which were written by the CEO himself. They are all either confusing, confounding, haunting, beautiful, or bizarre. Some were successes. Many were colossal failures.

I have watched almost all of them, and I am here to tell you about them, in more or less chronological order. The output paints a picture of Tsuji as a man who wanted to become Walt Disney by force. One of the given explanations of the company name “Sanrio '' is itself a California dream: a portmanteau of the words “San'' as in San Francisco and “Rio '' as in river. Tsuji would travel to Walt Disney Studios in Burbank in the mid-70s, and while there introduce himself as “Japan’s Disney.” The company would eventually launch an ambitious $50 million dollar, self-distributed push into film. One film distributor in 1978 was skeptical: “It’s extremely difficult to market animated films unless you’re Disney. They’re going to get killed.”

I set out to create as complete a document of Tsuji’s ambitions as I could, and to ask the questions: how successful was Shintaro Tsuji in becoming Walt Disney? What is the legacy of this strange experiment? And what can we learn about the history of film, not just children’s films, from his shining successes and many disasters?

Chiisana Jumbo AKA Little Jumbo (1977) and Bara no Hana to Joe AKA The Rose and Joe (1977)

Little Jumbo is the first movie produced by Sanrio, a short based on a children’s novel by Takashi Yanase, the creator of Anpanman. Yanase’s first short actually predates Sanrio: the tragic yet beautiful The Kindly Lion (1970) produced by Tezuka’s Mushi Production, which he was allowed to direct after art directing Osamu Tezuka’s A Thousand and One Nights (1970), part of the adult-oriented Animerama trilogy that would end up tanking Mushi. Many key staff from Mushi ended up at either Sanrio or the newly formed Madhouse, with Yanase being a key link.

Yanase is an interesting figure. He was drafted into WWII in a non-combat role in China doing Kamishibai on behalf of the occupying army, an experience that clearly impacted him. He is mainly known for Anpanman, a series about a superhero who is made out of anpan (red bean bun) who feeds people. “No matter what country you are from, no matter where you stand, offering food to those who are hungry is a good deed,” Yanase once said. “It is justice in the most absolute sense.” Almost all of Yanase’s films and stories produced by Mushi and Sanrio have a bleakly pacifist bent.

Little Jumbo is also one of many Sanrio movies directed by Mushi production regular Masami Hata, who would go on to co-direct Little Nemo and the “good” Mario movie, Super Mario Brothers: Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach.

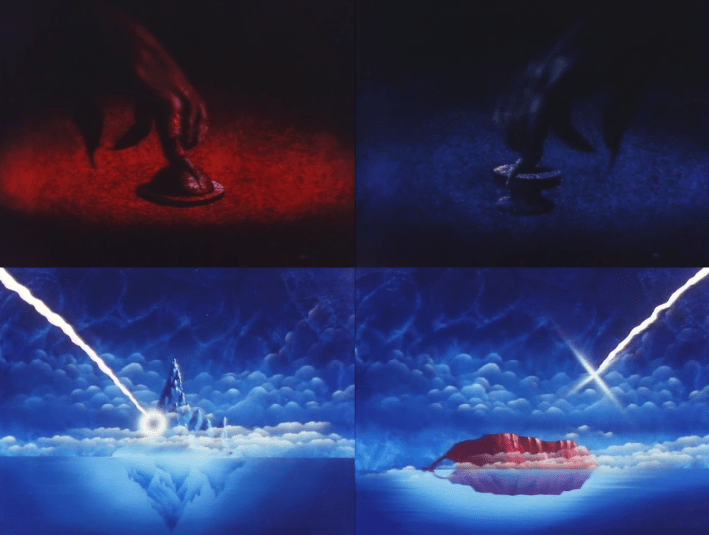

Little Jumbo starts off as a rollicking, groovy Yellow Submarine-style movie (Yanase was a fan) that descends into a dark, complicated metaphor for war, the suffering and cruelty of starvation and war rationing, and the evil of nations and mutually assured destruction. The film begins on an idyllic, secluded island called, appropriately, Beautiful Island. It is a paradise with dancing plants where everyone can be lazy. One day the flower king arrives, and with his red flying finger demands that his subject be diligent and toil. Suddenly, a mysterious red box arrives on the island, and out pops the heroes of the story, Baloo the elephant trainer and his elephant Jumbo. Baloo has a whip, but stresses that it is only for making noise, and Jumbo is happy to hear it.

Bombs start flying. Beautiful Island is caught in the crosshairs between East and West. The king is distraught, the air and the land are poisoned, the sun is blotted out and his subjects are starving to death. The king demands Jumbo’s death. Baloo pleads, but then says he will kill Jumbo painlessly with the whip. But Jumbo is too trusting to know what he is doing, and Baloo cannot do it. He begs the king to kill him instead and feed him to his servants, since nobody will grieve the death of an orphan. Everyone apologizes, and the moment is broken by East and West island pressing the final button (with clawed, demonic hands) that ensures mutual destruction and ends the war. Jumbo is injured, but alive.

Everyone sings at the end:

“We are all alive

We smile because we are alive

We are all alive

We’re happy because we are alive.”

It is a depressing message, but ultimately one of hope. The song that appears in the middle and reprised at the end, “Raise Your Hand To The Sun,” predates the movie by several years, originally gaining in popularity on NHK’s Mina No Uta in 1962. It would then be used later with great effect by Masaaki Yuasa in a pivotal scene in (huge spoiler if you have not seen this) the final episode of Ping Pong The Animation.

The Rose and Joe is somehow even more depressing. Also based on a Yanase short book, it’s a tragic story of two star crossed lovers, a lonesome dog and a rose. What follows is a tragedy about the fleeting nature of life and the selflessness of love, as Joe the dog attempts to defend his love against the forces of nature. It’s about 20 minutes long, and like many films here has a gorgeous soundtrack. The song where Joe and the Rose first meet is deeply touching, and sounds like a ballad straight out of a Yakuza film. I highly recommend you watch the entire thing yourself.

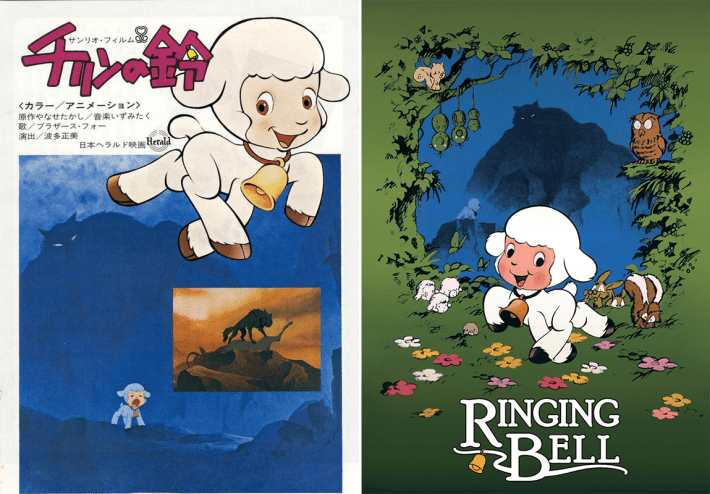

Chirin no Suzu AKA Ringing Bell (1978)

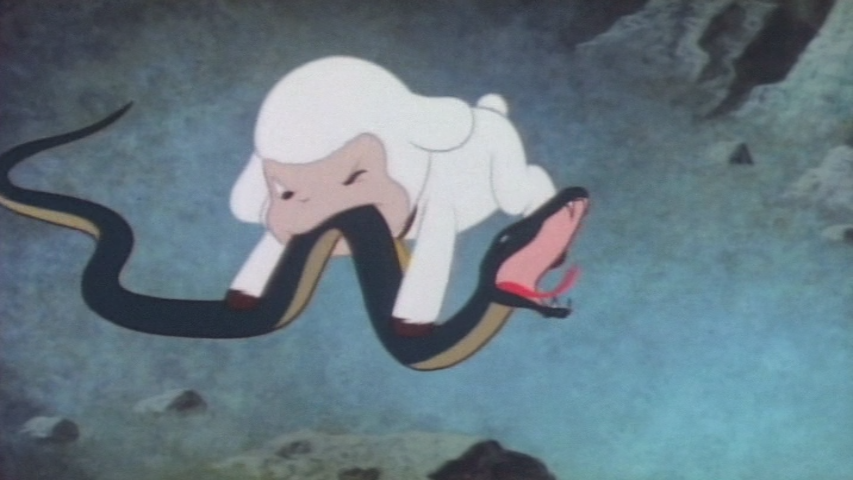

Ringing Bell is one of the most severe children’s movies in history, in the same category as Watership Down and The Secret of NIMH. Like the previous two entries, it is adapted from a book by Yanase. The movie stars Chirin, a little lamb with a little bell. Chrin’s lamb mom warns him never to go beyond the fence, because beyond there is a wolf named Woe who wishes to feast on the flesh of the lamb.

One day Woe kills Chirin’s mother while he’s asleep under her. What follows is a tale of vengeance: Chirin, distraught, seeks out Woe demanding his mother’s life back. Woe slaps the lamb aside easily. The next day Chirin returns and demands to become Woe’s pupil. “A strong wolf is so much cooler than some weak sheep that just tiptoes around!” Chirin says to Woe. Woe ignores Chirin, who continues to persist. At one point, Chirin sees a snake kill a bird’s mother and, in the process of defending the nest, destroys the eggs. “Why do the weak always die?” he asks. “Someone has to die,” Woe responds, ”so that someone else can live.” The wolf agrees to train the lamb, who vows to train until one day he will kill his master.

I won’t spoil the second act, but you should watch the entire movie yourself. Ringing Bell is a story of raw force, how it corrupts and how violence only begets more violence, and how alienation and isolation are ultimately the fate of the lone wolf. It is a hell of a thing to put in a children’s movie, and seems to reflect Yanase’s experiences in the war. “It is incredibly difficult to perform good deeds without bringing harm to oneself,” Yanase said in an interview.

I also think it’s a more coherent movie than Bambi, one that sticks the landing and doesn’t shy away from the brutalities of nature and man. Given the choice, I wish I had seen this as a child instead.

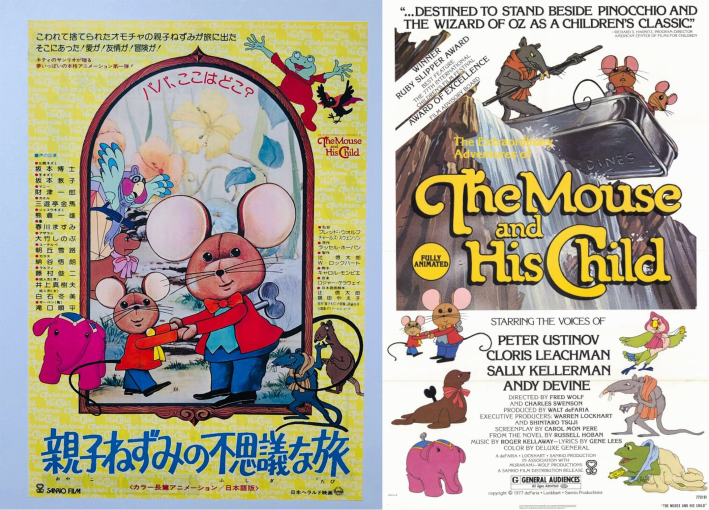

The Mouse and His Child AKA Oyako Nezumi no Fushigina Tabi (1978)

They don’t make cartoons like The Mouse and His Child any more: ponderous, somewhat cryptic films about wayward toys. The Mouse and His Child predates The Brave Little Toaster (a direct inspiration to Toy Story) by about a decade. It’s based on a book by Russell Hoban, a writer of fiction for both adults (such as the post apocalyptic novel Ridley Walker and Turtle Diary, which Harold Pinter would adapt for the screen in 1984) and many children’s books, including Emmett Otter’s Jug Band Christmas, which would then be adapted into one of my favorite Christmas movies by Jim Henson.

The Mouse And His Child is a very slow movie. The New York Times did not like it, saying that its main problem is that it was for adults, and that it was far too obtuse for children. This is true, and the pace can be difficult to stomach. The movie is about a windup toy mouse and his son, who are joined at the hands and dance when they are wound up. They live in a toy shop, and one day hope that all the toys can live together like a family. While dancing, they fall into a garbage can and end up in a dump. What follows is a journey through the wilderness, running across a rat colony that works enslaved toys to death, a whimsical frog who lives in a glove, a theater troupe, and a turtle who’s written a play called The Last Visible Dog. That scene in particular is by far my favorite, as the turtle speaks in cryptic, pretentious language about infinity, pondering a dog food can with an infinitely recursive label where the dog on the can is holding the can he is on. It’s tonally similar to the psychedelic river boat scene in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, a menacingly cryptic moment that comes and goes without explaining itself.

Unlike many of the movies in this era of Sanrio’s output, The Mouse and His Child has a happy ending, literally ending on a man saying to the toys, “Be happy.” It was directed by Charles Swenson and Fred Wolf of Fred Wolf Productions, who had previously animated Harry Nilsson’s The Point and would eventually do the Ninja Turtles cartoons. You may also know Fred Wolf Productions from their work on the “How many licks?” Tootsie Roll commercial, which I mention because it shares a tone with this picture. Imagine that commercial stretched over an hour and 20 minutes and you have The Mouse And His Child.

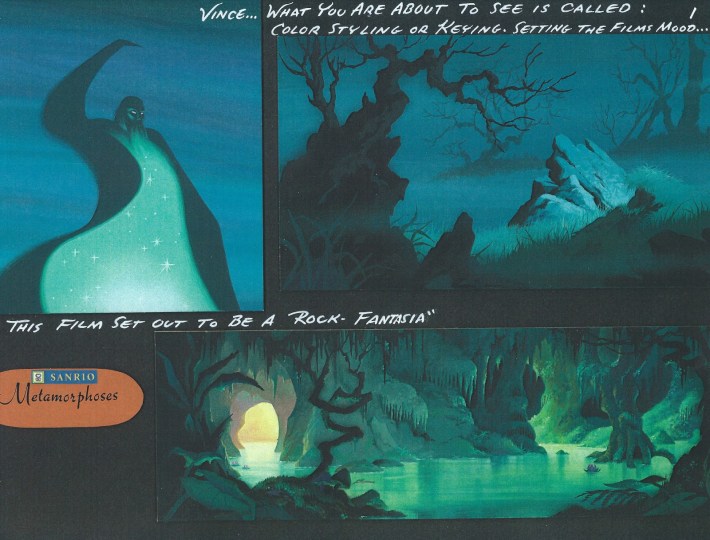

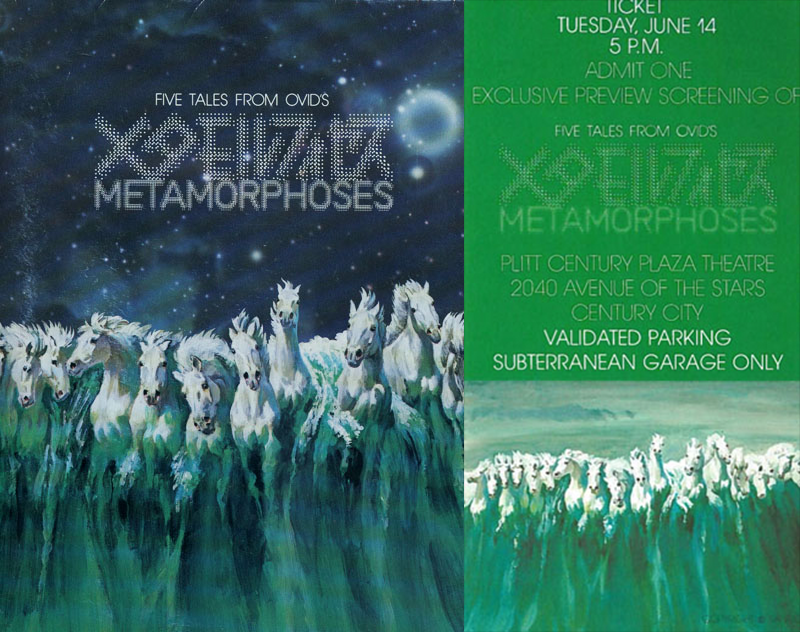

Metamorphoses (1977) AKA The Winds of Change AKA Hoshi no Orufeusu (“Orpheus of the Stars") (1978)

Metamorphoses was supposed to be big. Sanrio had Fantasia-sized ambitions, a theme that repeats itself often, and Metamorphoses was their attempt at creating Fantasia for the rock age. It was a 70mm epic in Panavision-Technicolor with six channel sound and original music by Mick Jagger, Joan Baez and the Pointer Sisters. I can’t get concrete numbers although Variety reported during its production that it cost more than 2,400 million yen or $12,000,000 dollars. It was produced entirely in Los Angeles with 170 American animators, and headed up by Takashi Masunaga (credited simply as Takashi). Masunaga had previously been working as a background artist at Hanna-Barbera, and had come up with and pitched the idea himself. A number of very talented artists worked on this movie, including Ron Dias, a background artist whose work you’ve seen in Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace, and The Secret of NIMH.

Metamorphoses recounts Ovid’s classic tale of the same name. The entire movie stars a single boy named Wondermaker taking five various roles in different segments. First is Actaeon stumbling upon Artemis bathing. This is followed by the myth of Orpheus’ descent into the underworld to find Eurydice, Mercury and the envy of Aglauros, Perseus defeating Medusa, and finally Phaëthon’s attempt to ride the chariot of his father Helios.

Metamorphoses bombed hard. Viewers were not familiar with Ovid, and did not understand why the same character was reprising the same roles, because there was no narration or explanation to contextualize it. The animation was jerky and uneven. Even a Sanrio spokesperson later admitted that the film in its original form was “incredibly difficult” to understand. Cartoon historian Fred Patten attended a screening in Century City, where attendees were given limited edition posters by artist Mo Gollub (an artist most famous for his covers of Turok and Tarzan); to quote Patten, “The orchestral pop-rock music was so deafening that it literally drove some of the audience out of the theater. It was rumored that it was so loud that plaster was flaking from the ceiling, while Takashi was complaining, ‘Can’t you turn up the sound any louder?’”

After the tremendous failure of Metamorphoses, producer Walt De Faria was brought in to reshape the movie into something less unprofitable. He threw out the rock soundtrack, and hired French disco impresario Alec R. Costandinos (also responsible for disco variants of Romeo and Juliet and Hunchback of Notre Dame) to write an entirely new soundtrack. The order of the segments was also rearranged. De Faria brought in British actor Peter Ustinov to narrate the American version of the movie, with Norman Corwin doing punch up on the script.

The resulting product is deeply strange, a ribald, urbane British actor riffing over disco versions of Greek myths. The movie didn’t work before, and what it was reworked into didn’t work in a completely different way. But to everyone’s credit, the main track “Red Hot River of Fire,” sung by disco legend Pattie Brooks, absolutely screams.

This movie was rereleased as Winds of Change in America and Orpheus of the Stars in Japan. The music is very slightly different in the Japanese, with a different song playing in the scene where Orpheus plays his song in the underworld and a different song in the credits. And instead of one ribald character actor playing out all the parts, several do. What’s more, the narration and scripting in the Japanese version is handled by Tampopo director Juzo Itami.

I do not know what became of the 70mm print of Metamorphoses, a totally original edit with a culturally important original rock soundtrack. As much as I enjoy the goofy disco version, every version of the movie released for home video has been tremendously rough, and cropped to 4:3. I’d love to see, just once, what they originally had in mind.

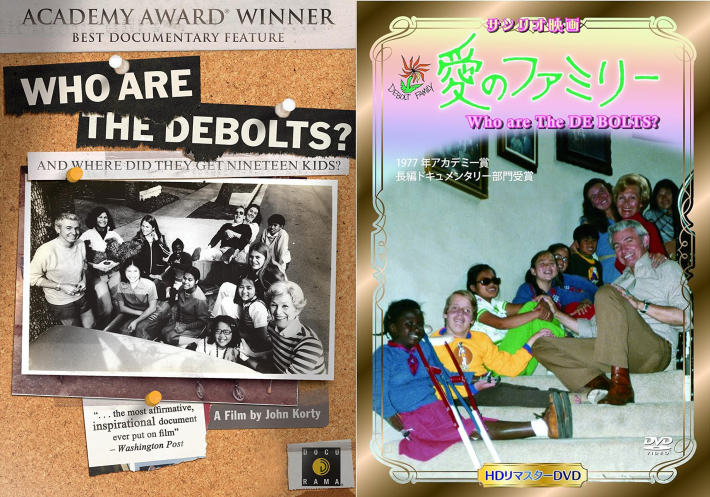

Who Are the DeBolts? And Where Did They Get Nineteen Kids? (1977)

Who Are The DeBolts? And Where Did They Get 19 Kids? is technically the first feature length theatrical release that Sanrio ever financed, co-produced with Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates. Adapted from 19 Steps Up the Mountain: The Story of the DeBolt Family, the documentary tells the story of Dorothy DeBolt (previously Dorothy Atwood), who bore five biological children and adopted two Korean children with her husband in her first marriage. Her first husband passed from cancer fairly young, and following his death she adopted two additional children, this time from Vietnam, both of whom had disabilities. Eventually she met and married Bob DeBolt, who had one daughter from a previous marriage. The couple went on to adopt 10 more children, many from various backgrounds and many of whom had disabilities.

Much of Who Are The DeBolts? is about the basic functioning of a family this large. Dorothy buys things wholesale from restaurant suppliers. Bob says outright that they are only able to take care of the medical expenses of their kids because there are programs that subsidize them. They extend their interest into advocacy, helping to found Adopt A Special Kid (AASK), which in 2015 became part of Lilliput Children’s Services.

Trying to figure out why the DeBolts created such a huge family crystallizes when you realize they are in the Bay Area; the story of the DeBolt family is overwhelmingly a Californian one in its idealism. At one point Dorothy recounts that she did not think to ask what part of Vietnam two of her children were from, she didn't give a damn, because they were kids and needed help. This film is constantly haunted by the specter of American imperialism, first in Korea and then in Vietnam, that has caused many of these children to end up adopted by the DeBolts in the first place.

But the movie attempts to paint a picture of a family that is loving, diverse and charitable, where everyone is given a chance for a good life. Much of the film emphasizes the ways in which the children are encouraged to live and work independently, with one scene following Tich and Anh’s paper route, which they deliver on crutches–a route that other kids gave up for being too difficult. Children take care of their chores, and more importantly each other.

Who Are The DeBolts? would go on to win the 1978 Oscar for best feature length documentary. A recut version narrated by Henry Winkler was rebroadcast on TV, and won him and the filmmakers two Emmy nominations and a win. A sequel was produced with Kris Kirstoffoson hosting called Steppin' Out: The DeBolts Grow Up.

Dorothy died in 2013, followed by her husband Bob in 2016. At that time, he was survived by 18 of his 20 children, 27 grandchildren as well as 6 great-grandchildren.

Olly Olly Oxen Free AKA The Great Balloon Adventure (1978)

Olly Olly Oxen Free is rough. This is a balloon movie starring an elderly Katherine Hepburn. Nothing happens for the first 12 minutes: a couple of kids look for stuff for a balloon, and then Hepburn shows up as an elderly junk lover and starts chewing the scenery. I quickly lost count of the number of times she referred to something as “simply grand.” It takes nearly an hour before they get into a hot air balloon. The New York Times review of the movie praised Hepburn’s presence but said that the movie was “so soft-spoken and gentle that bland is its dominant style.” I would really like to know how this movie got pitched, aside from someone saying, “We would love Katherine Hepburn to be in a movie, is she around?” On the plus side, you do get to see Katherine Hepburn dangle out of a big hot air balloon.

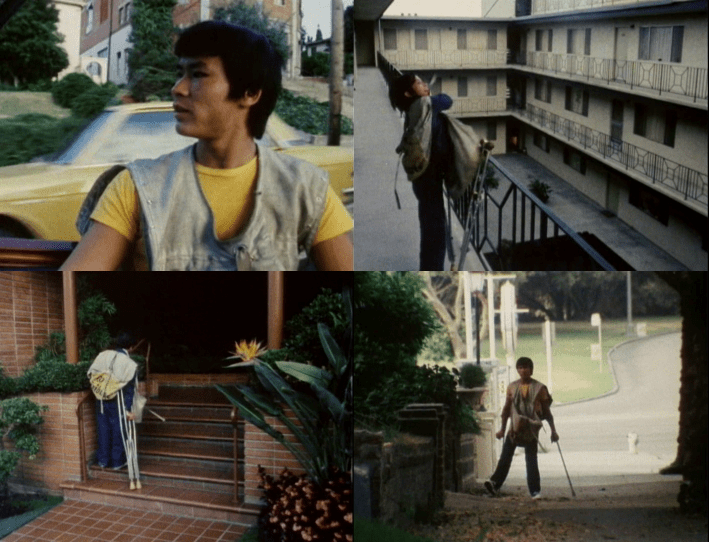

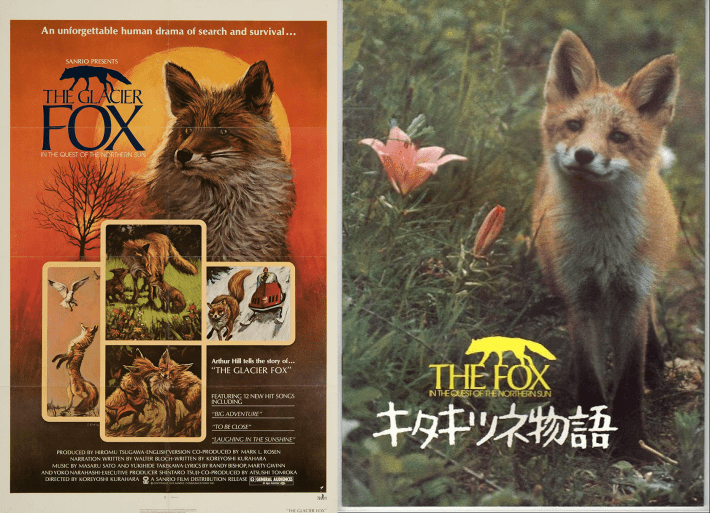

Kita kitsune Monogatari AKA The Glacier Fox (1978)

Kita-kitsune Monogatari is a family-oriented “documentary drama” about a family of foxes. It follows the story of Ezo red foxes in northern Japan. It originated as an idea from Shintaro Tsuji, who had read about the lifecycle of foxes in an academic journal. Originally intended to be a half hour TV show, the scope widened once Koreyoshi Kurahara got involved with the project, becoming a 2 hour long, rock-filled docudrama. The movie cost more than 2 million dollars and a crew of 30 shooting over 4 years, using specially designed telephoto lenses. This all resulted in over 700,000 feet, or about 150 hours, of film.

The soundtrack for this movie rules. It is done by Yoshito Machida, pop singer Miyuki Maki and rock band Godiego, who you may know from doing the song “Monkey Magic,” the theme to Galaxy Express 999 and the soundtrack to House (1977). Contributing to this was composer and long-time Akira Kurosawa collaborator Masaru Sato. Every track is a stone cold heater, even when translated and performed in English.

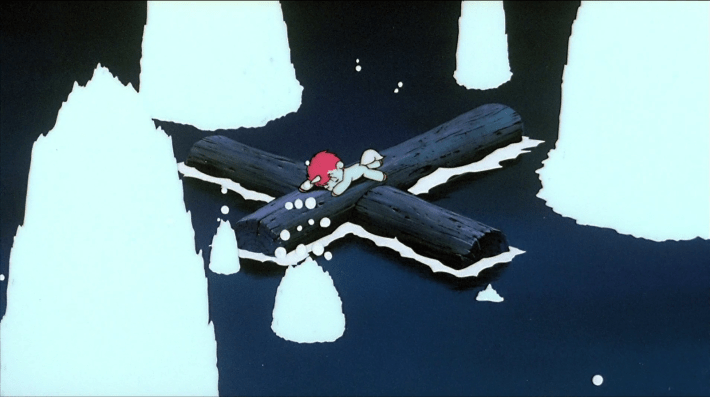

The film is gorgeously shot and often haunting. It’s narrated by a large oak tree, explaining the process by which foxes Layla and Flip meet, mate and raise a family together - a skulk of adorable baby foxes. The family grows and attempts to survive, hunting wild animals and raiding local farms.

While there’s some incredible shots of foxes in the wild, there are multiple parts of this movie that are clearly more drama than documentary. Animals die in this film; sometimes this is at the hands of other animals, sometimes at the hands of people. It is not pleasant to watch, and the film crew does not intervene in those moments, often following an animal as it flees. What’s more, some of the circumstances around the animals’ deaths, particularly near the end, seem very off. Some injuries and deaths look real; others clearly less so. Variety at the time concurred, saying of the American version that "the story [the narrator] tells can be believed only by the very young and uninitiated." I can’t think of a reason why a camera crew would, for example, film a hunter over the shoulder as he points the gun at one of their foxes. And maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t think animal blood has the consistency of canned tomato purée. This is perhaps appropriate, given the history of Disney.

This movie made a lot of money, making at least $15 million dollars in Japan alone. Producer Terry Ogisu pinned the success of the movie on the fact that Japanese audiences were “very sentimental and very patient,” which he knew Americans were not. It would eventually be brought over to America as The Glacier Fox, cut down by about 30 minutes and with the narration done by Canadian actor Arthur Hill instead of Woman In The Dunes star Eiji Okada. This movie would get repeated airtime on the Disney Channel, so if you have a vague memory about watching a real sad movie about a bunch of foxes, it was probably this one.

Kita-kitsune Monogatari is hard to find, even in Japan. I have imported the DVD twice after first mistakenly buying a version called Kita-kitsune Monogatari 35th Anniversary Renewal Edition. This version is a re-edit, a very strange one at that, with worse modern music, new narration and actors. It is also trimmed down by about 30 minutes, and the frame is cropped from its original 4:3 to 16:9. They clearly made it to update the movie for today's kids, but Koreyoshi Kurahara died in 2002 and so I don’t consider it worth watching unless you’re really curious.

Kurumiwari Ningyou AKA Nutcracker Fantasy (1979)

Sanrio was not content with cel animation alone. If Nutcracker Fantasy reminds you of Rankin/Bass stop motion, there is a good reason for that: Rankin/Bass outsourced its stop motion to MOM Production in Tokyo, the same people who handled Nutcracker Fantasy. Director Takeo Nakamura actually co-directed The Little Drummer Boy as well, although his contribution was uncredited, which feels like it should be illegal. People like to talk about anime as if it is a recent phenomenon, but American companies have been doing this for decades. Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer is an anime, most people just don’t know it.

Nutcracker Fantasy is based on E. T. A. Hoffmann’s story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. Most people are only vaguely familiar with the Tchaikovsky ballet based Dumas’ adaptation of the story, which severely simplifies and truncates the narrative. Sanrio’s stop motion picture takes details from both versions, but is much closer to the original with some key differences. The mysterious toymaker Uncle Drosselmeyer is in both and gives Clara a nutcracker, although in the Sanrio movie he also appears as a mysterious character known as the “Ragman”. In the Sanrio version Clara follows him into the clock into the Doll Kingdom. Like in the original, a princess is cursed by the Queen of the Mice (called Queen Morphina in the movie) although instead of being given a gigantic head and jaw she is made to look like a mouse. The king seeks help to fix her in both versions, although in the Sanrio version it’s a goofy extended bit with multiple wise men. And in both cases the solution to the curse being broken involves the nut Crackatook.

Nutcracker Fantasy is so much better than much of the studio’s Rankin/Bass output. I say without hesitation that this is one of the most beautifully animated stop motion movies I’ve ever seen. The sets look like something out of Superia: there is a gorgeous, psychedelic dimensionality to the piece. It also creatively mixed in live action elements, like a puppet fortune teller, a live ballet performance, and one of the most troubling scene transitions involving a clown I have ever seen.

Nutcracker Fantasy got multiple releases, and the Western release includes voices by Christopher Lee, Roddy McDowell and Dick Van Patten, although it cuts some very good material from the end, including the aforementioned clown. The movie would eventually be rereleased in 3D in 2014, cropped from its original 4:3 to 16:9, with art by Sebastian Masuda, a pop artist mainly known for directing singer Kyary Pamyu Pamyu. Just watch the original.

Kitty to Mimmy no Atarashii Kasa AKA Kitty and Mimmy’s New Umbrella (1981)

It’s also worth mentioning another stop motion movie by the same director: Kitty to Mimmy no Atarashii Kasa or Kitty and Mimmy’s New Umbrella. This short, just shy of 25 minutes, is the first outing of Hello Kitty in film (although she makes several small cameos in movies throughout this list). It’s a light, fun little film, not particularly tragic, and a humble start in film to a character that would, in the end, go on to define Sanrio more than anything listed here.

The Unico Movies:

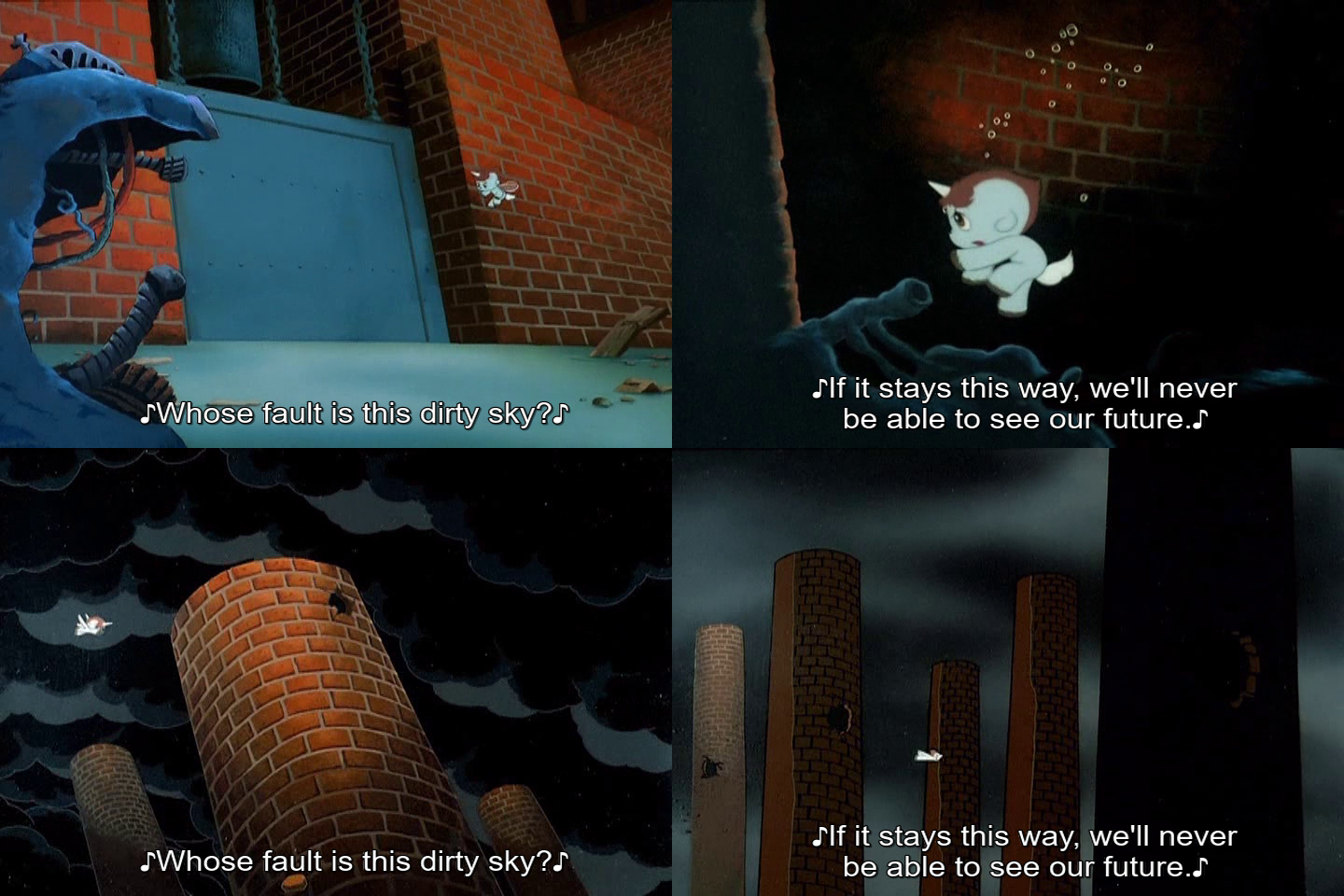

Unico: Kuroi kumo to Shiroi Hane AKA Unico: Black Cloud White Feather (1979)

Unico AKA The Fantastic Adventures of Unico (1981)

Unico: Mahô no Shima e AKA Unico in the Island of Magic (1983)

Sanrio would finance three movies based on the iconic manga Unico by Osamu Tezuka. But Unico was born in America, and would not exist were it not for Sanrio Film. The idea for Unico came to Tezuka while visiting the production studio working on the failed Metamorphoses in Los Angeles. He quickly sketched the character Unico on a piece of paper. Tezuka had been asked to do a serialization for Sanrio’s Lyrica magazine, which it also briefly attempted to publish in the United States. On the plane ride back from LA to Japan, Tezuka came up with the name Unico.

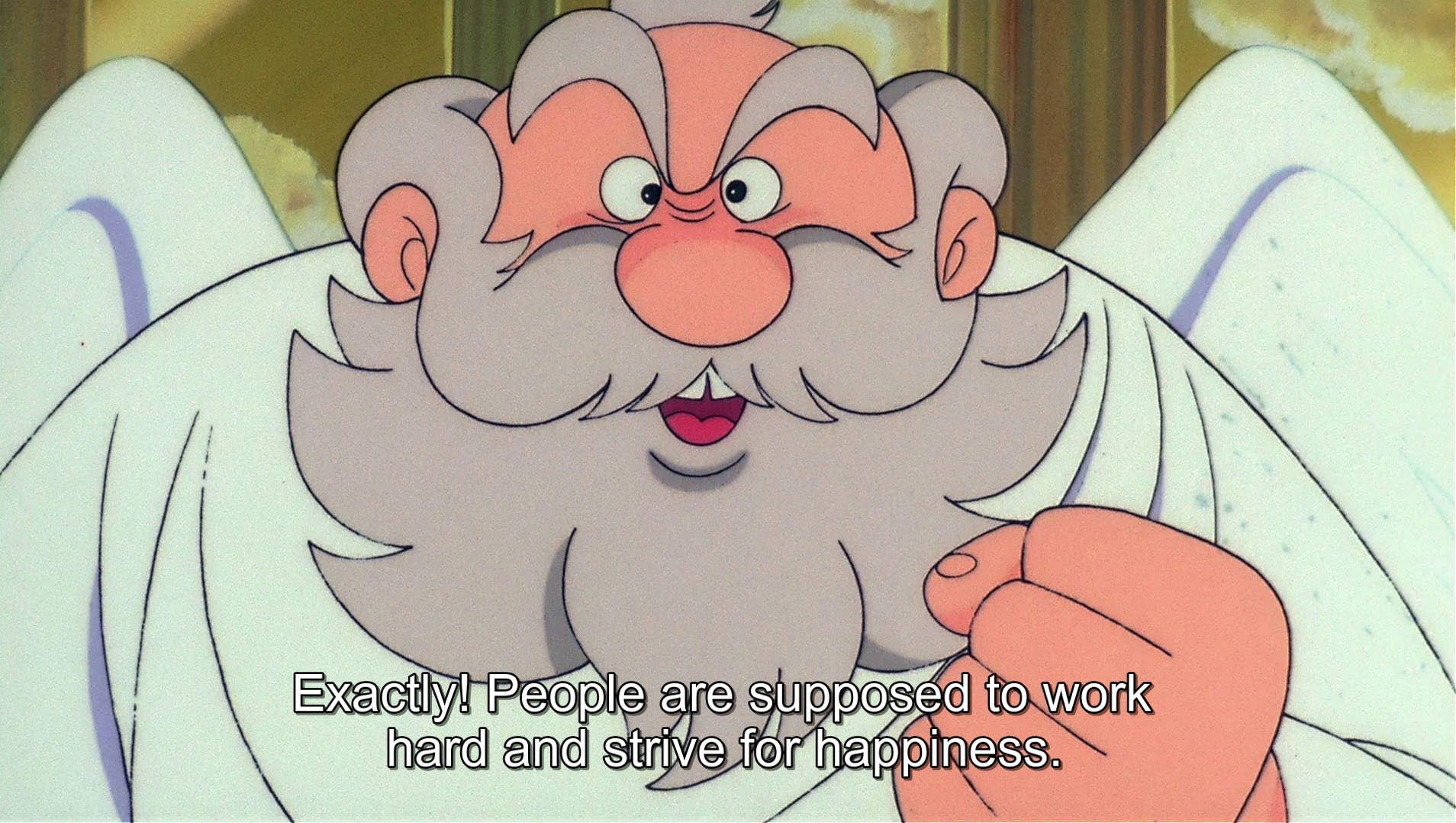

Unico’s backstory, like Metamorphoses, is set against the backdrop of Greco-Roman mythology. In the manga and the first movie, the goddess Venus is jealous of a girl (Psyche in the manga) and orders a femme version of the west wind Zephyrus to take Unico away from her to make her miserable. In the first feature, Venus is simplified to “The Gods,” and their rationale is that Unico makes people happy too easily, and thus should be banished to the Hill of Oblivion. In all versions, the west wind takes pity on Unico, and brings him on various adventures to make people happy. Unico can also transform into a mighty adult unicorn, but only through the power of true love. At the end of every adventure, however, the wind must do its duty and take Unico away, erasing any memory of the friends and people he met. Unico is allowed momentary, fleeting happiness, but cursed by the gods to be unable to hold on to it.

Unico: Black Cloud White Feather was the first of three movies. Originally it was meant to serve as the pilot for a Unico series, but was rejected. It was directed by Toshiro Hirata, who, like many who had previously worked at Tezuka’s Mushi Productions, would eventually leave for Madhouse. The subsequent two films would be produced by Madhouse. Black Cloud, White Feather adapts Chapter 4 of the manga. Unico arrives in a city covered in smog and meets a little bedridden girl who is sick because of a factory that belches smoke. What follows is an environmental story of redemption where Unico destroys the evil factory in an act of ecoterrorism. As the lyrics of the song go:

“Whose fault is this dirty sky?

If it stays this way, we’ll never be able to see our future.”

The Fantastic Adventures of Unico shifted production over to Madhouse, becoming the first feature the studio would do. This one in turn adapts two chapters of the manga (Chapters 8 and 3 respectively). The first part of the movie focuses on Unico befriending a child demon of solitude before being spirited away.

The second part of the movie shifts to Unico befriending a cat named Chao, who wishes to be a human witch, and her budding friendship with a normal elderly woman whom Chao wrongfully assumed to be a witch. Once Unico turns Chao into a human, Chao attracts the attention of the enigmatic Baron Ghost, the ruler of the forest.

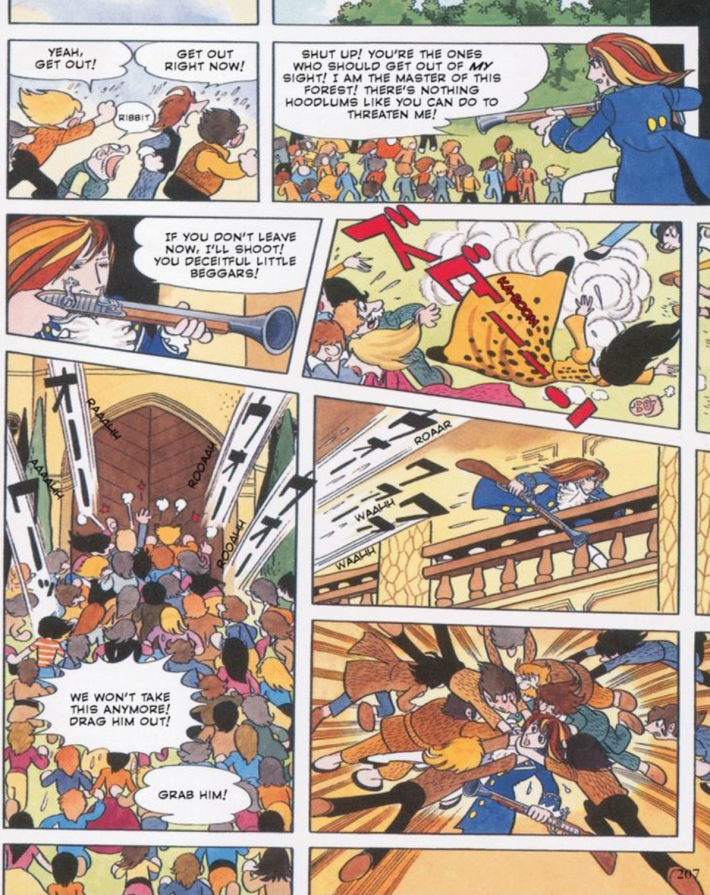

This is the part where the manga and the film diverge wildly. In the movie, the Baron is depicted as a Dracula-like figure, who turns the animals evil with magic and who Unico must confront in a surreal confrontation that would be terrifying to watch as a child. In the manga, the Baron Ghost is an evil aristocrat who takes pleasure in killing animals for sport, hanging their heads on the wall as trophies. Unico solves this by turning all the animals in the forest into people and having them storm the Baron’s castle, tearing him apart in a proletariat rage. While I find that ending cooler and much more cohesive, I can see why they went the big scary monster route for the movie.

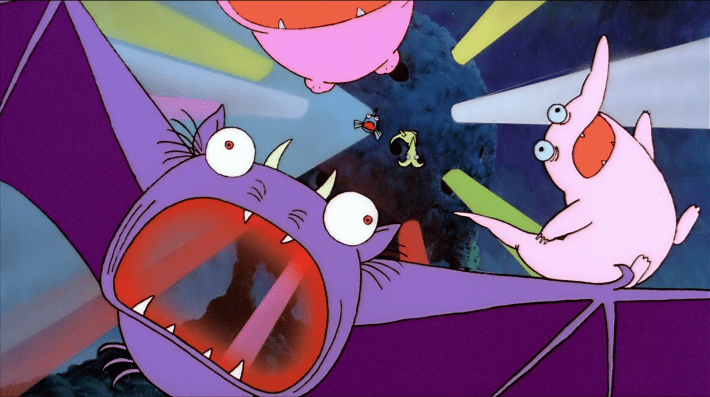

Unico in the Island of Magic (1983) is the odd duck in the trilogy. The main plot is unrelated to any arc in the manga, although the second act adapts a portion of Chapter 6. It is less a Unico movie in the purest sense but more a movie with Unico in it, that Unico solves. In his wanderings, Unico ends up on a mysterious island beset by an enigmatic magical flutist in a bug-like costume named Toby, who is turning the animals and people into magical dolls at the behest of his master, an evil wizard named Kukurukku. The dolls are then loaded onto ships to construct the foul mage’s island, forming the iridescent walls of the castle.

(Flashing video warning below)

Though Tezuka’s touch is felt less here narratively, the entire movie is surreal beyond measure. Kukurukku is animated like a menacing red orb with a shifting crone’s face, and the character is a masterclass in how to emote in cartoons. The island fortress is guarded by a massive robotic dinosaur that would feel at home in Super Mario World. The sheer quality of the animation and its strong personality cannot be overstated, going above and beyond the already impressive feats of The Fantastic Adventures of Unico, and cementing Madhouse as a force to be reckoned with along with Harmagedon, which came out the same year. All of the Unico movies are worth watching, but The Island of Magic is something truly special. To quote a stranger on Twitter, “I feel lucky to have grown up watching this.”

While the Unico movies have their bleak and terrifying points, at no point do they ever hit the lows that Yanase’s works do. Tezuka’s worldview was far less shattered than Yanase’s, and though Unico is tragically fated to wander forever, his is a story of love, hope and charity. Unico is eternal, and though he wanders, through him you can achieve salvation.

Afurika Monogatari AKA A Tale of Africa AKA Green Horizon (1980)

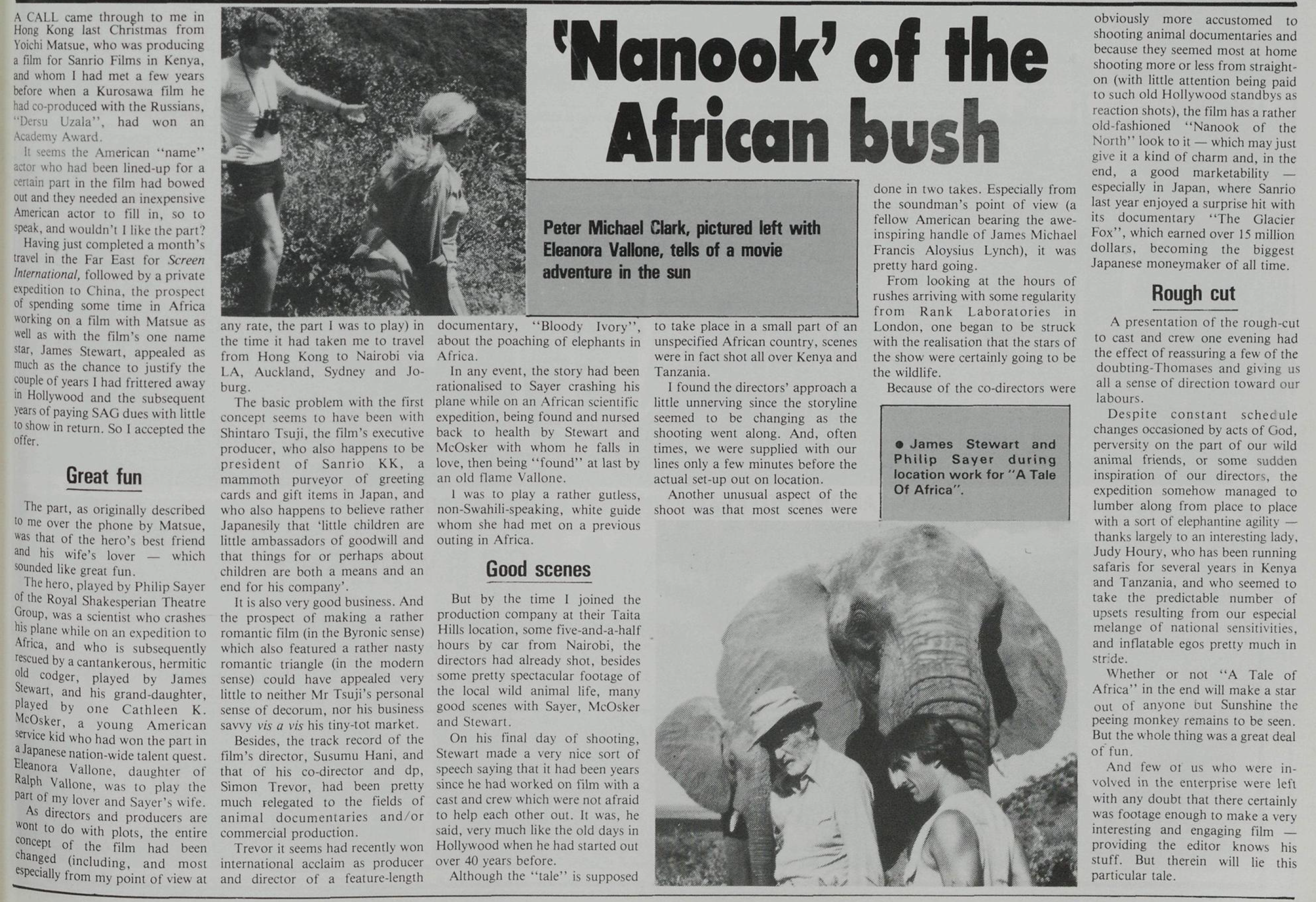

A Tale Of Africa is the last live action film performance by James Stewart. He’s tremendously old and not in it a lot, but that isn’t the wildest part. The wildest part is that he was not supposed to be in this movie. Stewart just so happened to be visiting the game preserve the movie was being shot at in Kenya and just sort of agreed to be in the movie.

The tone of A Tale Of Africa is deeply strange, slow to the point of being almost avant garde. It’s a stretch to call it good, but it is fascinating. Nothing is really said in much of the first 30 minutes, and in many ways it feels more like a nature documentary than fiction (the movie being co-directed by documentarians). Stewart plays a Dr. Dolittle type, credited simply as “old man,” living in a cabin with his cool granddaughter and many animal friends. The girl, played by Kathleen McOskar and credited simply as Kathy, had apparently won this role in a nationwide talent contest.

Eventually this tranquility is disrupted by an amnesiac British plane crash survivor, played by Philip Sayer, who wanders into their life and falls in love with Stewart's granddaughter. Soon the amnesiac’s fiancé attempts to track him down. Stewart’s health deteriorates, and his conflicts with local poachers escalate. Eventually the fiancé tracks the amnesiac down at Stewart's grave, attempting to give him his old dart gun and return him home. The amnesiac refuses, stating that this is his home now. As he walks away, his fiancé shoots him. In the next scene, which feels suddenly tacked on, he’s made a complete recovery. From context, I would guess that the original vision for this beat was much darker.

The movie was co-directed by Susumu Hani, an avant-garde director known for Nanami: The Inferno of First Love, one of the greatest movies of the Japanese New Wave. Hani had previously worked internationally, directing a series of well-received TV documentaries set in Africa as well as the drama The Song of Bwana Toshi (1965). In addition to Sanrio CEO Shintaro Tsuji, A Tale of Africa also features a story credit by Shuji Terayama, an incredibly important filmmaker and writer of the Japanese New Wave with whom Hani had collaborated. On top of this, Hani’s co-director was Simon Trevor, who had made a name for himself with his documentaries The African Elephant and Bloody Ivory, about poachers.

A Tale of Africa doesn’t really hold together. According to actor Peter Michael Clark in Screen International, the plot was constantly shifting, with a love triangle subplot removed, possibly at the behest of CEO Shintaro Tsuji. In addition to this, most shots were done in two takes, much to the frustration of the soundman. There is a sense that the bones of a much better, more ambitious movie are peeking through, a drama with a bit more bite, but what is delivered is inoffensive with beautiful nature photography. Variety hated this movie, filing one of the funnier vintage reviews I’ve seen: “Stewart, despite drawling such patent falsehoods as ‘elephants are friendly,’ nonetheless appears ill at ease around these and other beasts. All the more incongruous than that his home should be infested by all manner of little critters performing cloyingly cute stunts.”

As with many of these movies, the soundtrack rocks. The track “Yume no Flamingo,” which appropriately plays against a backdrop of flamingo flocks, is a particular banger.

The Sea Prince And The Fire Child AKA The Legend of Sirius (Shiriusu no Densetsu) (1981)

Unlike other movies on this list, you can actually stream The Sea Prince And The Fire Child legally and in high definition (although the blu-ray from Diskotek is unfortunately out of print).

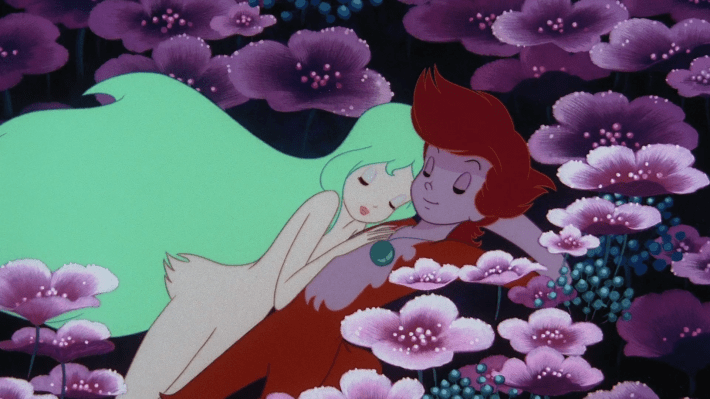

Directed once again by Masami Hata, the story follows two tribes of mythical creatures, the tribe of the Fire and the Tribe of Water. Ages ago, Fire and Water were one, but then war between the two peoples forced them apart forever. It’s against this backdrop that a star-crossed romance blooms between the princess of Fire, Malta, and the prince of the Water, Sirius.

The Legend of Sirius looks breathtaking: Though many of the characters have a goofy quality, the backdrops are striking and evoke a Fantasia sensibility that feels borderline illegal now. The other thing that knocks you on your ass is how hard they sell the romance between what are essentially two teen fairies.

Helping sell all of this is the score, composed by Dragon Quest composer and war crime denier Koichi Sugiyama. Say what you will about the guy (no really, please), the score rocks. It’s a genuinely haunting soundtrack, pitch perfect for the tone of the movie, unlike the boring marching band music he would eventually put out later in his life. On top of this, it’s based on a story by Sanrio CEO and founder Shintaro Tsuji, and some animation by Ninja Scroll director Yoshiaki Kawajiri.

If you only see one movie on this list, this is in the top 2, along with at least one Unico movie. It fires on all cylinders, and has a haunting message about love that transcends the ages. “When someone’s love is true,” the king of the sea finally states, “that love cannot be a sin.”

A note about The Ideon

I have frequently seen reference online to the two Space Runaway Ideon movies, The Ideon: A Contact and Space Runaway Ideon: Be Invoked, as being co-produced by Sanrio. I could find no source to confirm this information. I was not the only one: Mike Toole at the Anime News Network also looked into this, and could find no primary source in any of the press material. I spoke to a Japanese Sanrio blogger, who also found this puzzling. I will update this piece if I find information confirming this.

Don't Cry, It's Only Thunder (1982)

Don't Cry, It's Only Thunder was written and co-produced by Vietnam veteran Paul G. Hensler at the urging of Francis Ford Coppola, who he’d previously worked with while consulting on Apocalypse Now.

A dying soldier in the Vietnam War asks a medic named Brian, played by Dennis Christopher, to care for a Vietnamese girl he pulled from a combat zone on to a helicopter. Brian ends up becoming the sole benefactor of an orphanage run by Catholic nuns who cannot keep up with the endless flow of children orphaned by the bloodshed. Brian helps by stealing supplies from the military base he’s stationed at, which in this movie’s defense is one of the cooler things you can do while in the military, which is portrayed as a comically corrupt institution. Don’t Cry, It’s Only Thunder is relatively neutral on the topic of the war itself, depicting it almost as a force of nature rather than something the main character is complicit in as a medic, although one of the nuns condemns America to Brian’s face for its role in perpetuating the war. Additionally, most of the Vietnamese people in the movie are either innocents saved by Brian during his personal journey, or broadly drawn stereotypes of enemy Vietnamese combatants (one of whom smuggles a bomb in a basket of puppies to place in a GI’s jeep). Probably the most human interaction in the movie involves Brian attempting to escape the military on a motorcycle, crashing, and being quickly hidden by an elderly florist who knows him for helping the orphanage, but even this interaction is done in a slapstick “hey buddy, you’re all right” kinda way.

Hensler, who would pen a book of the same title, was motivated to write the screenplay and book based on what he felt were unfair depictions of Vietnam veterans in movies as exclusively mentally ill. This is one of the few movies from the era that attempts to give a modicum of compassion to victims of the Vietnam War, although it comes explicitly as part of the coming of age of a white soldier. Weirdly, I think there is something to the idea of exploring the moral ambiguity of a soldier attempting to do a tiny bit of good in a situation his government created. But as previously mentioned, Yanase understood the contradictions of this dynamic, and the impossibility of doing good short of making someone a meal. What’s more, any potential reality of the situation is paved over with cheap Holywood bombast. In the end, Brian gets the girl, a child he tries to adopt tragically dies, he becomes a hero to the orphanage, and then his tour is over. As one poster for the movie states without irony, the movie is “suggested by a true story.” The result is not very watchable, but is a fascinating milestone in the American military’s attempt to rehabilitate itself after unconscionably leveling multiple countries.

On a lighter note, Don’t Cry, It’s Only Thunder features a bit part with Robert Englund AKA Freddy Krueger as a soldier who keeps getting STIs and eventually steals a bunch of condoms from the army.

Oshin (1984)

Directed by Belladonna of Sadness director Eiichi Yamamoto, Oshin is an anime feature film that shares a cast and plot with the serialized NHK Morning Drama (15 minute episodes called asadora for short) of the same name. The serial begins in the spring of 1983 and follows a grandmother who runs her family’s local regional supermarket chain on the opening of its 17th location. Yet during the big day she leaves and heads mysteriously north to the mountains of Yamagata. Eventually the story shifts backward in time to her remembering her youth, and it is this flashback that Sanrio’s Oshin takes as its source material.

Though the Morning Drama of Oshin has been translated and uploaded, I could not find subtitles for the animated movie and had to resort to machine translation, context from the subtitled show, and what Japanese I know. In that light, it’s hard to give me a fair assessment of the movie, but narratively it’s a very direct adaptation of the show: a slow, maudlin drama about a poor daughter of a sharecropper family persevering through various trials and tribulations in Japan through the Meiji era, a narrative about the resilience of women by a woman. While not a showpiece, it isn’t poorly animated; many of the backgrounds in particular are breathtaking. That said, the anime does not use the medium’s strengths well, and has the pace and plotting of a Morning Drama turned into a cartoon. It does a good job at summarizing the major beats of the first 36 of the 297 episodes of the show (minus the framing story), and I was able to watch both TV series and movie in different windows and see exactly which scenes matched.

The plot itself is too winding and circuitous to summarize, but one scene in particular is worth mentioning. In both the asadora and anime, Oshin befriends a deserter of the army called Shunsaku. He attempts to teach Oshin about compassion and pacifism, and in the process reads a poem by poet Yosano Akiko called "Thou Shalt Not Die" (Kimi Shinitamō Koto Nakare), a famous anti-war poem urging her brother not to fight in the Russo-Japanese war. It’s a beautiful poem worth sharing here, and a tremendously haunting thing to listen to when trying to research the history of the company that made Hello Kitty.

Yousei Furorensu AKA Fairy Florence AKA A Journey Through Fairyland (1985)

Having whiffed it on an earlier attempt to bring Fantasia to life with Winds of Change, Sanrio took one last shot at it with A Journey Through Fairyland. Once again directed by Masami Hata and written by Shintaro Tsuji, it’s the story of a young, absent-minded boy studying the oboe who loves playing music for flowers. One day he rescues a begonia he finds on the ground, and the spirit of the flower, a fairy named Florence, brings him on a fantastical journey through Flowerland. Save for a single song (a love song by Florence) the entire movie is set to orchestral music. The plot is really the least important part of this movie; like Fantasia, the entire point is to see incredibly complex animation set to classical music. You got Strauss, Beethoven, Schubert, Bach, Mozart, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and more. There are also a few numbers done by composer Naozumi Yamamoto, who is known for scoring the Tora-San movies – a series about a lovable vagabond who strikes out with the ladies that has, I am not joking, 48 installments (for context, there are currently 26 James Bond movies).

If you own a bar, A Journey Through Fairyland is in the same category as Zardoz, Barbarella and Liquid Sky: a fantastic thing to put on a TV and have drunks ask, “What the hell was the name of that movie that was playing the other night?” It is a slightly less traumatizing or confounding movie than the rest of the Sanrio film catalog from this era. Like classical music, it’s a little dry for some people. A nice thing going for it is you don’t need to pay attention to the plot to enjoy it. It exists less as a movie and more as a series of cool images and sounds that you can drift in and out of. It’s just a nice movie, save for one scene closer to the end where the boy suddenly kills a Lovecraftian Great Old One for reasons I am still sort of unsure about.

Omoide wo Uru Mise AKA L'echoppe Aux Souvenirs (The Store of Memories) (1986)

I thought I was done with this article after A Journey Through Fairyland, but out of nowhere, I found this one by poking around second-hand website Mercari Japan. The Store of Memories doesn’t have much of an internet footprint in the West, and the IMDB is somewhat of a void. It isn’t online anywhere, save for a trailer uploaded by Sanrio a few years ago. It features music and an introduction by French easy listening pianist Richard Clayderman, stars French actor Philippe Caroit, and seems to be adapted from a book of the same name about a shop that sells memories by Sanrio CEO Shintaro Tsuji with illustrations by queen of cute Setsuko Tamura.

I had to proxy buy a used copy of this movie just to be able to watch it. The entire movie save for Clayderman’s introduction, which is in subtitled French, is in dubbed Japanese. And because there was no way to watch this movie online, and my Japanese is patchy at best, the best I can do is a machine translation. Luckily, it’s not that complicated a plot.

It’s the story of an old man named Joseph who sells people the ability to relive their memories (the sign outside his shop reads “Chez Joseph Souvenirs”). He does this by mixing a potion that they use to blow a soap bubble, which then crystallizes into a precious, bittersweet memory from their past. An old woman remembers seeing her child off on a boat, who then subsequently died in a shipwreck. Another woman fondly relives a memory of frolicking in the flowers with her love, who died in combat. Eventually, a man named Tom (Philipe Caroit) darkens Joseph’s door, and at the old man’s suggestion relives the courtship with his long lost love Marie. Tom is a simple country boy who dreams of being a glass blower, and Marie’s adopted family are upper crust and do not approve. Tom goes to Venice to study glass making, only to be betrayed by one of his close colleagues. If you only watch one part of this movie, it should be the scene in the middle where Tom does really elaborate glass blowing for several minutes. When he returns, it is revealed that Marie has been pining for him, reliving her memories, the same way Tom has been for Marie. The two reunite, and embrace.

The Store of Memories is a very strange movie, rife with interesting contradictions. It’s conceptually heartbreaking while still being deeply saccharine. Clayderman’s music is corny but strangely moving. I don’t know if this movie is supposed to be for children or sappy adults, which is made vague by the appearance of brief partial frontal nudity. It is simultaneously timeless but also could not exist in any time but the mid 80s. It is severely Japanese in tone, but also cloyingly French – a Japanese tourist’s idea of what that country is like. It is, in a word, Ghibli-esque.

There might be a reason for that: According to a former Sanrio animator on Twitter, Miyazaki and Takahata were involved in the planning of this movie at some point before it became a live-action movie. I would like to stress that this is unconfirmed on my end, although I have reached out to the Ghibli Museum for confirmation. Thematically it would make a kind of sense. It shares certain similarities to the movie Whisper of the Heart, with the main love interest being a luthier instead of a glassblower, and the focal point of both being an elderly man with a shop of magic (Whisper of the Heart is based on a manga, but some of these details in the adaptation differ). And if it had been planned, it would have been in the period just prior to the formation of Ghibli. It would also not be the first time that Miyazaki and Takahata had left a planned project before it was complete, the other notable one being Little Nemo in Slumberland, a movie famous for being in development hell and being described as the worst professional experience of Miyazaki’s career before eventually being completed by a familiar face: Sanrio regular Masami Hata.

Anyway, check out the mustache on this dude.

Loose Ends: Kaze no Fantajī: Ōmurasaki no Uta AKA Fantasy Of The Wind: O-Murasaki’s Poem (1985) and “Juliette”

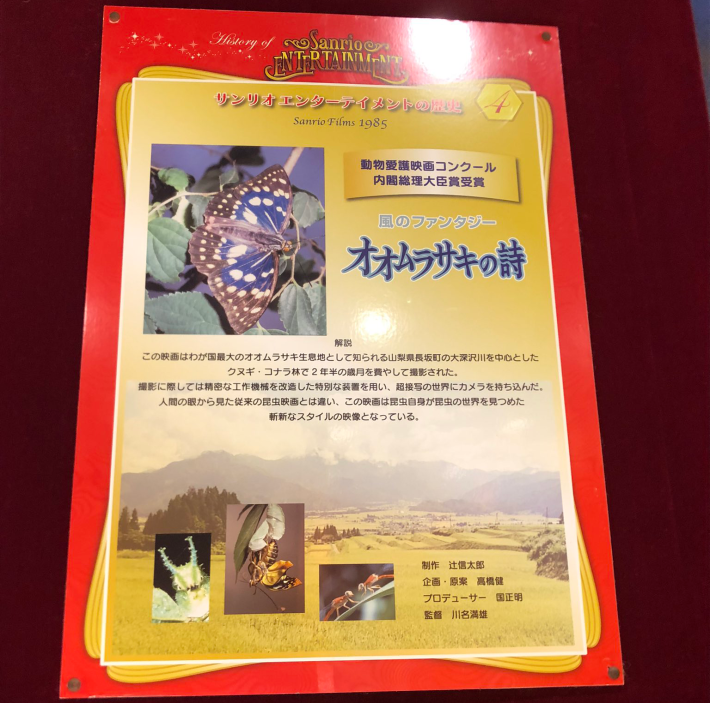

One person who has been instrumental in this article, A Sanrio blogger who goes by pinky1030rocks on Twitter, sent me photos of their recent trip to Sanrio’s theme park: Puroland. In Puroland, there is a small display case dedicated to Sanrio’s film accomplishments. On display are several movies that are well known: Who are the DeBolts?, Metamorphoses, The Sea Prince and the Fire Child, and then one other I had not seen: a documentary from 1985. Seemingly titled Fantasy of the Wind: Ōmurasaki’s Poem, it appears to be a nature film about the Japanese butterfly sasakia charonda or Great Purple Emperor (known in Japan as ō-murasaki or great purple) shot over several years in Yamanashi prefecture. This all scans, as Hokuto City has an entire wildlife refuge dedicated to the Ōmurakasi butterfly, and Shintaro Tsuji himself was born in neighboring Kōfu. I cannot find any other information about this movie, but I hope to watch it one day.

There is one other loose end worth discussing. In a 1979 issue of Boxoffice magazine, there is one mention of a potential project that never got off the runway. Titled simply, “Juliette,” producer Terry Ogisu described it as “a very large project” with screenwriter John McGreevy adapting a story by Tsuji about “the adventures of a 16-year-old-girl who takes over a business empire when her father dies.” According to Tsuji, it was meant to be shot in America with an American writer, director, and cast, his answer to The Sound Of Music. I could find no other mention of this movie.

"Japan’s Disney"

So did Shintaro Tsuji become Japan’s Walt Disney? On some level, sort of. Though often forgotten today, Tsuji’s film ambitions were wildly idiosyncratic and scaled beyond the scope of profitability, like many of Walt Disney’s projects. Many of the films are clearly influenced by Fantasia, appropriate given that Fantasia was not profitable in its initial run due to extenuating circumstances. And after the strange, less-than-decade long foray into films, what would ultimately define Tsuji’s legacy are the branded, merchandised characters like Hello Kitty. Following 1986, Sanrio would scale down its film ambitions, focusing mainly on shorts involving its licensed characters. And in 1990, Sanrio would open Sanrio Puroland, a small Disneyland of its own, as Hello Kitty would become a figure on par internationally with Mickey Mouse. Shintaro Tsuji would be president of Sanrio from it’s founding in 1960 until 2020. He is currently 96 years old.

But what struck me again and again when I was watching many of these movies is their impossibility today. I do not mean this in a reactionary or nostalgic way: These movies only exist through sheer eccentric willpower. And while the results were sometimes plodding and confusing failures, every single one of them contains the seed of something fascinating – either a beguiling fact, a breathtaking soundtrack, or a moment of shocking beauty.

Often when I posted about one of these films, a person would mention that it had a formative effect on them as a child. They would mention a film being seared in the reptile part of their brain, an old and half-remembered dream, bubbling to the surface.

“Is this the one where all the people get turned into paper dolls,” someone asked me of Unico in The Island of Magic, “ because that one did some deep, lasting damage to my psyche as a child.”

“I watched this movie all the time as a kid and it destroyed my brain,” said another.

“I watched this movie so much growing up,” another said of A Journey Through Fairyland. “Sometimes, I thought I made it up.”

What Sanrio made was not always perfect, and occasionally not very good. But at its peak these films were classically tragic, and contained things truly memorable that feel no longer permitted in films for either children or adults. For better or worse, we used to allow kids to watch this kind of stuff, to be shaped by the strange ambitions of an idiosyncratic rich guy with a dream that scoped beyond profitability. Movies aren’t made like that anymore; they’re predictable investments financed by dull people. And that’s a pity, because I worry that kids today will not have the same experience of seeing a movie for the first time in 30 years, a freak that escaped containment and into syndication, and saying in YouTube comments, “I thought I dreamed this,” “I have been looking for this since I was five, “I will always remember this movie,” and “This movie destroyed me when I first saw it ... and it still does even now.”

Thank you again to blogger 絋@pinky1030rocks who provided the pictures Sanrio Puroland, and was instrumental in providing leads that are not immediately accessible in the west. Their blogs can be read here. Kelsey Short did the fantastic top illustration. Their portfolio can be seen here.